RIBA's Creation from Catastrophe exhibition showcases the world's best disaster-relief projects

A new exhibition about radical projects to rebuild communities in the aftermath of disasters points to the "changing role of architects in society", says its curator (+ slideshow).

Creation from Catastrophe at London's Royal Institute of British Architects focuses on the way cities and communities have been reimagined by architects in the aftermath of natural and manmade disasters.

Curator Jes Fernie told Dezeen that the exhibition shows an "expanded idea of what architecture is and what architects can do".

"The thing that is particularly relevant is the changing role of architects," said Fernie. "I'm not thinking this is going to radically change the way architects work but it presents people with an alternative to how architects can get involved in community activism and can take political approaches."

The exhibition covers almost four centuries, beginning with London after the 1666 Great Fire and Lisbon after the 1755 earthquake.

It ends with the bottom-up, community-led approach that defines the practice of many 21st-century architects including Pritzker Prize winners Shigeru Ban and Alejandro Aravena.

"There is a merging of approaches," said Fernie. "We have presented it as relatively black and white, but there are examples all over the place of bottom-up in the 19th century and evidently there are many of top-down now."

"But there is still definitely this idea about the failure of Modernism and the idea that you have a sole author creating a vision for the future has been pretty much debunked or almost problematised," she said.

Architects like 75-year-old Yasmeen Lari aren't just designing houses but teaching local people to rebuild houses and creating a chain of information, Fernie added.

This year's Pritzker Prize winner Alejandro Aravena is considered a champion of this kind of "participatory practice".

"We had no glass ball to look into to see Aravena would be winning the Pritzker Prize and heading up Venice," Fernie told Dezeen.

"It just became really pressing. Everyone was talking about flooding," said Fernie. "This isn't just about what is happening in Nepal or Chile, this is happening in England and America and Europe."

The exhibition includes drawings, photographs, film, books and models, many of which have never been seen in the UK before. The works are presented in a largely cork-covered space designed by young London-based practice Aberrant Architecture.

Creation from Catastrophe is on show in the Architecture Gallery of London's RIBA until 24 April 2016.

Dezeen spoke to the curator Jes Fernie about some of the key projects featured in the exhibition:

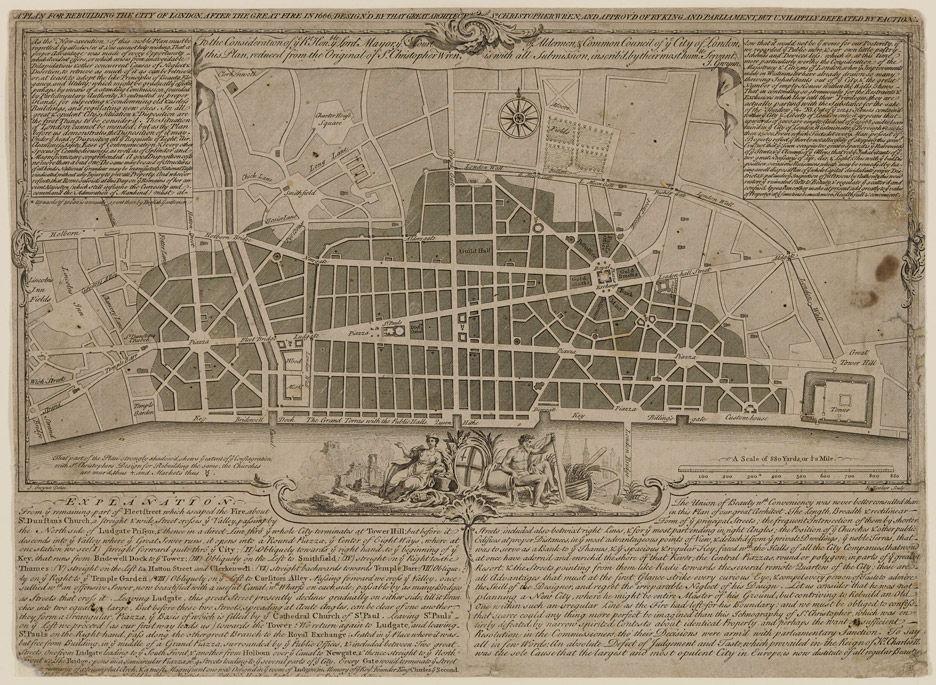

Sir Christopher Wren's plan for rebuilding the City of London after the Great Fire of 1666

Sir Christopher Wren's vision of London after the Great Fire of 1666 was for a modern, rational city. His masterplan outlined a formal street layout, which replaced the narrow streets that helped spread the fire with wide avenues that radiated from piazzas.

"It is really hard to overstate how radical Wren's plan was with its grand sweeping boulevards and piazzas," said Fernie. "There is evidence that people in Lisbon and Chicago even hundreds of years down the line looked at Wren's plan and thought, right we're going to do what you couldn't achieve."

"Had it been realised, it would have been seamless and beautiful no doubt and it would of taken on an identity quite similar to cities like Rome and Paris," said Fernie. "But there is no doubt that London would have lost some of its character and identity. The medieval streetscape remained in place and that's pretty much what we have today."

The Reliance Building by Atwood, Burnham & Co, North State Street, Chicago 1890-95

The Great Fire of Chicago in 1871 is considered by many to have given birth to not only an architectural style, the Chicago School, but also an architectural typology: the skyscraper.

"Basically, out of that fire came this great capitalist expansion," said Fernie. "There was this move to create an identity for Chicago and the future, and then of that came the Chicago School."

"The idea was that you had steel frames, sheet glass coverings and fire-retardant buildings, and out of that came the skyscraper that we all know today," she explained.

Atwood, Burnham & Co's Reliance Building, with its steel frame and large plate-glass windows, is one of the post-Chicago fire buildings that paved the way for modern skyscrapers.

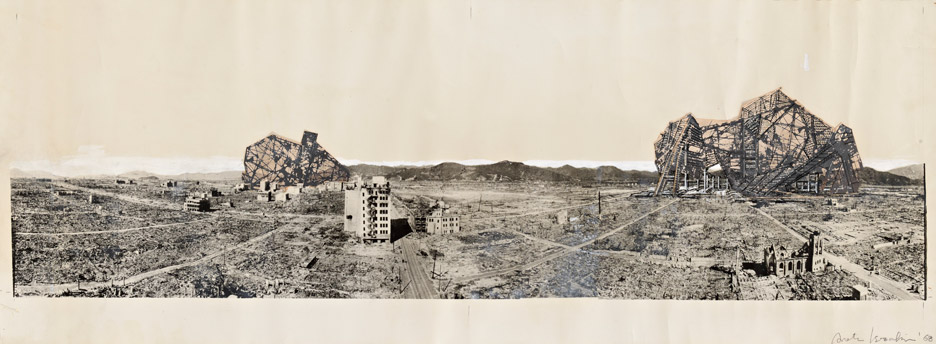

A photomural from Arata Isozaki's project Re-ruined Hiroshima, 1968

Two ruined metal structures stand in the devastated landscape of Hiroshima in this fantastical collage by Japanese architect Arata Isozaki. Made 23 years after a nuclear bomb was dropped on the city, the piece imagines Hiroshima as if it was rebuilt in line with the vision of the Metabolism architectural movement, only then to be destroyed by another disaster.

Architects in the post-war Japanese Metabolism group proposed megastructures and modular capsules that could withstand earthquakes and tsunamis, as well as grand visions for post-apocalyptic cities.

"I think that Metabolism is an amazing example of a practice that managed to look backwards as well as forwards," said Fernie. "They were really, really influential in the 1960s but there are lots of architects today who are still inspired by them."

"They were talking about environmental catastrophes long before other architects," she added. "The idea was that you build on pylons, or you build structures that are separated from the ground so that floodwater can come through and not demolish what is already there."

Post-tsunami sustainable reconstruction plan for Constitución, Chile by Elemental, 2014

Pritzker Prize-winning architect Alejandro Aravena's "do-tank" Elemental took a bottom-up, community-led approach to rebuilding of the Chilean city of Constitución after the 2010 earthquake and tsunami, working with nature and the community, and not against it.

"There is something incredibly simple and beguiling about [Aravena's] proposal, which is basically to propose that housing is demolished and in that place, forests are planted," said Fernie. "The idea is obviously that the roots absorb much more water than built-up land."

"The other thing about that project is that it deals with the disaster as an opportunity to effect change and do something that has long-term impact," she added. "This community was devastated by a tsunami and an earthquake but that only happens every 100 years. But when Aravena came to Constitución, what he discovered was that there was flooding every 10 years, so his project actually dealt with the short-term and the long-term."

Ideas for the rebuilding of Hoboken, New Jersey after Hurricane Sandy in 2012 by OMA

During Hurricane Sandy in 2012, 80 per cent of Hoboken in New Jersey was submerged under water. The area is particularly susceptible to flooding, and the hurricane emphasised the need for a flood defence strategy. Rem Koolhaas' firm OMA proposed a solution with a combination of hard infrastructure and soft landscaping that would create a coastal defence integrating natural drainage.

"The [Elemental and OMA projects] are very similar in that you are not creating a barrier for water but inviting it in," said Fernie. "OMA came up with a multi-pronged approach: resist, delay, restore and discharge. This is a really complex water system and acknowledges that it has to be approached in many different ways, from storing and discharging to changing land use from one to another."

"I think the thing that is interesting about the comparison is the cultural differences between North American approaches to living with disasters to perhaps Dutch ones," she said.

The Women's Centre, Darya Khan, Pakistan, designed by Yasmeen Lari in 2011

Pakistani architect Yasmeen Lari, 75, has built over 36,000 homes for flood and earthquake victims in her home country since 2010. Lari's organisation, the Heritage Foundation of Pakistan, employs architecture students to train local residents to build more resilient homes using local materials like bamboo and mud.

"Yasmeen Lari uses ancient architectural traditions and teaches the people in villages to rebuild their own houses," said Fernie. "A lot of the 21st-century projects in the exhibition are kind of changing the role of architects of society – Lari isn't just designing houses that get built but she is teaching architects and local people to rebuild houses. And it is like a chain, that information gets carried on."

Lari is particularly concerned with addressing the needs of women, who are disproportionally effected by natural disasters because they are usually the carers of children and providers of food. Structures like the Women's Centre in Darya Khan address these issues. "The idea is that the women can meet there, they have their own social space, there is space for children to play," said Fernie "There is also, in the event of a flood, a first floor where waters won't reach."

Housing for 2015 Nepal earthquake victims by Shigeru Ban

After the 2015 Nepal earthquake, Pritzker Prize-winning architect and champion of disaster-relief architecture Shigeru Ban developed a prototype housing structure for the victims.

Ban based his modular housing on traditional Nepalese houses that had survived the earthquake. Wooden frames provide the structure, the roof is built using a truss system of cardboard tubes, rubble is used to infill the walls, while thatch and plastic sheeting covers the roof.

The simple construction method enables anyone to assemble the wooden frames very quickly.

"Ban builds the frame and lets local people create an infill with rubble and bricks from the earthquakes," said Fernie. "It is the same bottom-up approach as some of the other projects, helping people to literally and metaphorically rebuild their lives."

Design for water communities, Lagos, Nigeria by NLÉ

Founded by Nigerian architect Kunlé Adeyemi, Amsterdam studio NLÉ has developed building systems for vulnerable areas on Africa's coast that have little or no permanent infrastructure thanks to unpredictable water levels.

The practice's research project African Water Cities aims to create new infrastructure, embracing living with water as opposed to fighting it and reclaiming land. Projects realised thus far include a floating school, and there are plans for a radio tower and a whole floating community.

"There is clearly a thread running through NLÉ's practice," Fernie told Dezeen. "It is that you use rising sea levels to your advantage. So you build on top of water rather than build a structure that has to rebuff or fight against water with the rising tides."