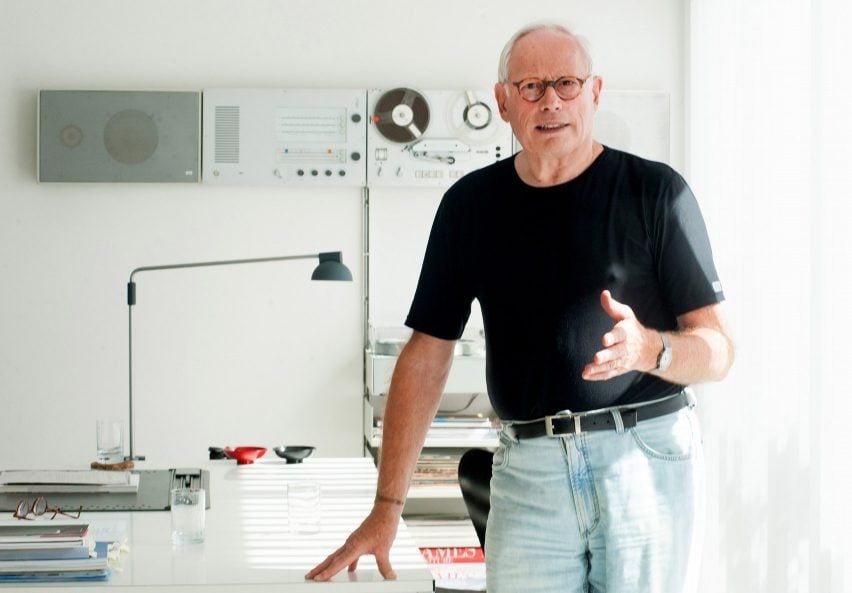

"Simplicity is the key to excellence" says Dieter Rams

In a rare interview, German designer Dieter Rams has called for a return to well-made, long-lasting products, even if it comes at the expense of design innovation.

In the interview, published in the latest issue of Kinfolk, Rams said that restrained aesthetics and optimised functionality are key to creating products that will endure, even if these qualities "act as a constraint upon innovation".

"I have always tended to steer well clear from this discussion about beauty and argued instead for a design that is as reduced, clear and user-oriented as possible, and simply more bearable for a longer period of time," he said.

"The only plausible way forward is the less-but-better way: back to purity, back to simplicity," he added. "Simplicity is the key to excellence!"

Rams, 84, was head of design at Braun from 1961 to 1995, where he established himself as one of the most important industrial designers of the 20th century. His iconic designs ranged from watches and calculators, to audio equipment and furniture.

He is seen by many as the biggest influence on the pared-back aesthetic of Apple's bestselling products.

His latest comments reiterate the values he promoted in his Ten Principles for Good Design, which were first published in the late 1970s, and argued that the long-term usefulness of an object is intrinsically linked to how it looks.

"We really should consider very carefully whether we constantly need new things," he said. "I have been arguing for a long time for less, but better things."

Rams has also compared his achievements at Braun with the work of fellow German designer Peter Behrens – mentor to architects including Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier – in showing "the value of collaboration between top management and design".

"When I arrived at Braun in 1955, their products were still conceived by engineers and detail engineers and censored by salespeople," he said.

"In the early years, we began working on a more modest product language that derived from function but was stripped of the formal mendacity that was commonplace at the time. This was thanks to the appreciation and support given to design by the top management – in particular, Erwin Braun himself."

Dieter Rams' modular furniture recently went on show at the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein.

Dezeen Watch Store also stocks a collection of Braun watches, based on the designs that Rams created with colleague Dietrich Lubs. Shop now ›

Read on for the full interview with Rams, published in Issue 23 of Kinfolk:

Alex Anderson: You were an early pioneer of sustainability in its broadest sense, and a critic of wastefulness, visual pollution and triviality in design. Now that environmental sustainability has been in the public consciousness for a while, these broader issues are beginning to come around again. Would you agree with Lance Hosey, an architect and author on aesthetics and sustainability, who declared, "If it's not beautiful, it's not sustainable. Aesthetic attraction… is an environmental imperative"?

Dieter Rams: Beauty, not just appearance, that is both exemplary and instructive, certainly intensifies and prolongs the relationship with the user and therefore also makes sense ecologically.

In my 10 principles of good design, I have written that the aesthetic quality of a product is an integral aspect of its usefulness, for the appliances that we use daily have an impact on our personal environment and influence our sense of well-being. But a thing can only be beautiful if it is also well made. Of course, there are general criteria of beauty such as harmony, contrast or proportions, but individual aesthetic sensibilities can vary a lot and can also depend upon knowledge, education and awareness.

This is why I have always tended to steer well clear from this discussion about beauty and argued instead for a design that is as reduced, clear and user-oriented as possible, and simply more bearable for a longer period of time. But "simple" is especially hard to achieve; even Leonardo da Vinci knew that.

Simple is especially hard to achieve; even Leonardo da Vinci knew that

Alex Anderson: Does a conflict between practical utility and abstract beauty still encourage innovation in product design, or are there other more assertive mechanisms at play?

Dieter Rams: Calm, sober and intellectual surprises should always be possible with design. Practical value and beauty are not mutually exclusive, even today, and they are unlikely to be so in the future either.

For me, a restrained aesthetic and function that is as optimised as possible have always been important. These qualities lead to long utilisation cycles: The objects do not become visually unbearable after a short time because they have not pushed themselves into the foreground. Certainly, these qualities also act as a constraint upon innovation.

We really should consider very carefully whether we constantly need new things. I have been arguing for a long time for less, but better things.

Alex Anderson: Early on, artists, critics and manufacturers perceived two key benefits of industrial design: it made products both more desirable and more profitable, and it contributed to a general improvement of public taste.

You seem to perceive a third benefit of industrial design, which is that it reduces wasteful consumption by producing objects that people will like and hold on to, which in turn benefits the environment. Do you think the consumer product industries feel a conflict between those earlier goals and this newer one?

Dieter Rams: I completely concur with [German architectural and art critic] Adolf Behne that we need "comfort" instead of "luxury." He believed that really good design should not be fuel for consumption that brings us nothing but irreparable resource problems and environmental destruction.

There has been much and persistent talk about sustainable growth; it's time to do something about it! The only plausible way forward is the less-but-better way: back to purity, back to simplicity. Simplicity is the key to excellence!

Practical value and beauty are not mutually exclusive, even today

Alex Anderson: A number of authors have noted that your work was influenced by the Bauhaus. It seems more productive to think of your work as fulfilling the promise of Peter Behrens, widely considered the world's first industrial designer and mentor to Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius and many of their contemporaries.

Very early in his career, Behrens declared that there is "a liberating quality" to the union of practical utility and abstract beauty because these were so often in opposition to each other in his era. Part of his success later, it seems, is that he capitalised on overcoming this opposition – with appealing and often surprising results. During your career at Braun, did you sense any continuity with the pioneering efforts of Behrens in his role of creative consultant at German industrial design company AEG?

Dieter Rams: During the relatively short period of his position as artistic consultant to AEG, between 1907 and 1914, Peter Behrens did indeed – as one of the first industrial designers ever – have the opportunity to shape many areas of that company. What he succeeded with, above all, was overcoming historicism and also to a certain extent Jugendstil, which was so prevalent at the time. For me, his enduring achievement was that he showed clearly the value of collaboration between top management and design.

When I arrived at Braun in 1955, their products were still conceived by engineers and detail engineers and censored by salespeople. In the early years, we began working on a more modest product language that derived from function but was stripped of the formal mendacity that was commonplace at the time. This was thanks to the appreciation and support given to design by the top management – in particular, Erwin Braun himself. In this respect, there were clear parallel design goals to those of AEG.

I was most certainly aware of the Bauhaus culture during my studies at the College of Applied Arts in Wiesbaden. The founding director, Professor Hans Soeder, had based the school's curriculum on Bauhaus principles. Particular role models were Mies and Gropius, who had also both worked as assistants in Peter Behrens' office.

Alex Anderson: Are there products that you use regularly and that you particularly enjoy, or that you think exemplify the principles of design you developed and refined over the years?

Dieter Rams: My wife and I live in our house furnished predominantly, but not entirely, with products from Braun and Vitsoe. For example, the Vitsoe 606 Universal Shelving system: I designed it 56 years ago and still feel comfortable with it. When you live with products, you get to learn their faults so you can improve them and thus keep the designs alive for longer!