"How do you avoid a robot apocalypse?"

As automation places millions of us at risk of losing our jobs, now is the time to rethink how humans and robots will coexist on this planet, says designer Madeline Gannon in this Opinion column.

We are reaching an inflection point. For the past 50 years, robots have served us well: we told them what to do and they did it – to maximum effect. As a result, we have had unprecedented innovation and productivity in agriculture, medicine and manufacturing.

Now rapid advancements in machine learning and artificial intelligence are making our robotic systems smarter and more adaptable than ever. These advancements also inherently weaken our direct control and relevance to autonomous machines. As such, robotic automation, despite its benefits, is arriving at a great human cost: the World Economic Forum estimates that over the next four years, rapid growth of robotics in global manufacturing will place the livelihoods of five million people at risk, as those in manual labour roles will increasingly lose out to machines.

What should be clear by now is that the robots are here to stay. So, rather than continue down the path of engineering our own obsolescence, now is the time to rethink how humans and robots will coexist on this planet.

Advancements in artificial intelligence inherently weaken our direct control and relevance to autonomous machines

How do you avoid a robot apocalypse? What is needed now is not better, faster or smarter robots, but an opportunity for us to pool our collective ingenuity, intelligence and relentless optimism to invent new ways for robots to amplify our own human capabilities.

For some designers, working with robots is already an everyday activity. The architectural community has embraced robots of all shapes and sizes over the past decade: from industrial robots to collaborative robots to wall-climbing robots and flying robots. While this research community continually astounds us with their imaginative robotic fabrication techniques, the scope of their interest tends to be limited. They are primarily concerned with how robots build and assemble novel structures, not how these machines might impact us as they continue to join us in the built environment.

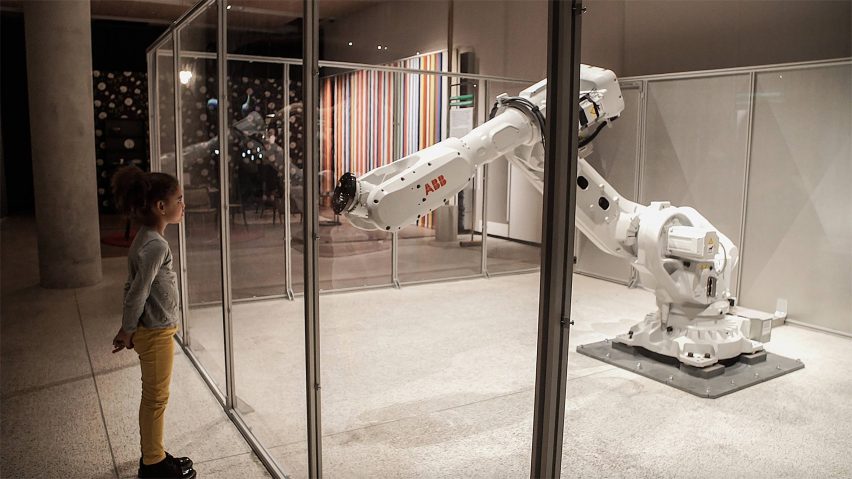

In my own work, this under-explored territory has become somewhat of an obsession. My training as an architect has given me a hyper-sensitivity to how people move through space, and I am striving to invent ways to embed this spatial understanding into machines. My latest spatially sentient robot, Mimus, created with support from Autodesk, lived at the Design Museum in London from November to April as a part of the new building's inaugural exhibition Fear and Love: Reactions to a Complex World. Mimus is a 1,200-kilogram industrial robot that I reprogrammed to have a curiosity for the world around her. Unlike traditional industrial robots, Mimus has no pre-planned movements: she seeks the most interesting people around her enclosure to interact with. More often than not, she gets bored of them quite quickly.

Madeline Gannon's Mimus, part of the Design Museum exhibition Fear and Love, was reprogrammed to have a curiosity for the world around her

To be clear, I do not anticipate most people will run into autonomous industrial robots on a daily basis. These machines are beginning to move out of factories and into more dynamic settings, but they will likely never stray too far from semi-controlled environments, like construction sites or film sets. However, experimental inquiries, such as Mimus, provide an opportunity to develop and test relevant interaction design techniques for the autonomous robots that are already roaming our skies, sidewalks, highways and cities with us.

A great example here is one of BMW's latest concept cars, which aims to mitigate miscommunication with driverless vehicles by "building up a relationship" between an individual and the car. To better communicate with the passenger, this machine's dashboard is fitted with 800 moving triangles, which open up to reveal red undersides to warn them of potential hazards on the road. However, even if self-driving vehicles are legally cleared to drive on the roads, the psychological question remains: are we willing to trust and build a relationship with autonomous cars, or will we always see them as industrial machines?

What is needed now is not better, faster or smarter robots, but an opportunity for us to pool our collective ingenuity

These newer, smarter robots — like drones, trucks or cars — share many attributes with industrial robots: they are large, fast and potentially dangerous non-humanoid robots that don't communicate very well with human counterparts. For example, in a town like Pittsburgh, where crossing paths with a driverless car is now an everyday occurrence, there is still no way for a pedestrian to read the intentions of the vehicle. This lack of legibility has led to some fairly disastrous results for autonomous car companies.

As intelligent, autonomous robots become a more ubiquitous part of the built environment, it is critical that we design more effective ways of interacting and communicating with them. In developing Mimus, we found a way to use the robot's body language as a medium for cultivating empathy between museum-goers and a piece of industrial machinery. Body language is a primitive, yet fluid, means of communication that can broadcast an innate understanding of the behaviours, kinematics and limitations of an unfamiliar machine.

Deciding how these robots mediate our lives should not be the sole discretion of tech companies nor cloistered robotics labs

When something responds to us with lifelike movements –– even when it is clearly an inanimate object –– we, as humans, cannot help but project our emotions onto it. However, this is only one designed alternative for how we might better co-habitate with autonomous robots. We need many more diverse and imaginative solutions for the various ways these intelligent machines will immerse themselves in our homes, offices and cities.

Deciding how these robots mediate our lives should not be the sole discretion of tech companies nor cloistered robotics labs. Designers, architects and urban planners all carry a wealth of knowledge for how living things coexist in buildings and cities – a knowledge base that is palpably absent from the robotics community. The future of robotics has yet to be written, and whether you self-identify as tech-savvy or a Luddite, we all have something valuable to contribute towards how these machines might join us in the built environment. I am confident that together we can create a future in which our technology expands and amplifies our humanity, and doesn't replace it.