"Everything changed in architecture" after 9/11 attacks says Daniel Libeskind

The terrorist attacks on New York's World Trade Center helped the public understand the importance of architecture, says the architect who masterplanned the rebuilding at Ground Zero in the next part of our 9/11 anniversary series.

Speaking to Dezeen in an exclusive interview, Polish-American architect Daniel Libeskind said that "everything changed in architecture" after the tragedy.

Prior to the attacks, he said, urban planning was largely done without public input. However, the attack on the Twin Towers revealed that big architectural projects "belong to citizens".

"I think that the impact [of 9/11] was on the whole world," he told Dezeen. "Everything changed in architecture after that. People were no longer willing to do it as before."

"It had an impact in the sense that people understood that big projects are not only for private development, they belong to citizens," he explained. "I think it gave people a sense that architecture is important."

On 11 September 2001, Al-Qaeda terrorists hijacked four commercial aircraft. Two were flown into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan, claiming 2,753 lives.

Another plane hit the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, while the fourth crashed into a field in Pennsylvania. The overall death toll of the four coordinated attacks was 2,996.

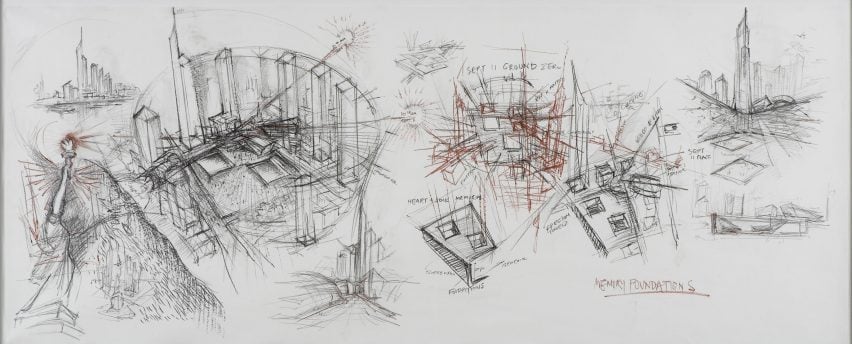

Two years after the attack, Libeskind won a competition to masterplan the 16-acre World Trade Center site.

His framework included a memorial and a museum to the tragedy, a transport hub plus a cluster of towers including a central "Freedom Tower" with the symbolic height of 1,776 feet, representing the year of America's independence.

However, Libeskind's Freedom Tower design was never built and instead One World Trade Center by SOM rose in its place.

Public participation became "much more important"

Libeskind attributes the fact that there was a design competition at all to public demand.

"There was no original competition at all for Ground Zero," he explained. "It was a port authority call for good ideas that they could use," he said, referring to the body that owns the World Trade Center site.

"It was the public that demanded what they saw, and luckily, [my idea] was the one that was in the eye of the public," he continued.

"The public said 'we want this project'...so the port authority was, in a way, forced by the public to implement something that originally was not part of their agenda."

Libeskind said that this "showed the power of the public in determining the future of their cities".

"Planning is not a private business," he added. "It should be determined by a democratic voice of all the different interests, which includes developers and agents, the people, you know, all sorts of different constituencies."

"New York is about tall buildings"

Following the attacks, Libeskind said that some people thought that tall buildings would no longer be built in the city and that Lower Manhattan would fall into a state of decline.

"The mayor of New York, Rudy Giuliani, just wanted low buildings," recalled Libeskind.

"People said nobody will ever come back to downtown, companies will move to New Jersey, they'll move to Connecticut," he continued. "People don't want to be there anymore."

However, Libeskind felt differently, saying that "New York is about tall buildings" and "always has been".

He compared the aftermath of 9/11 to the coronavirus pandemic, which some people predict will lead to the demise of dense cities and office working.

"Today with a pandemic, people say the same thing," Libeskind said. "People will not work with offices anymore." But he believes that "people will always come" back to cities.

Site "belongs to all of us"

Reflecting on his work on the Ground Zero masterplan, Libeskind likened its challenges to designing a whole American city.

While reintroducing office skyscrapers and adding valuable real estate to the site, he decided to dedicate half of the land to public space to create a neighbourhood accessible to everyone, rather than to just office workers.

"My main goal in the masterplan was, first of all, to create a civic space, not to just be concerned with private investment, but to create a significant memorial, which brings people going to the site in an open social way," he said.

"This was a commercial site where every square inch is worth a lot of money," he explained. "But I felt that somehow it's not a piece of real estate anymore."

"It's something that belongs to all of us," he said.

The Ground Zero masterplan is yet to reach completion, with KPF's 5 World Trade Center next in line to break ground. However, Libeskind believes it has already achieved his aims.

Recalling the day that Ground Zero reopened to families of victims, he said: "I still remember the words people said to me: 'Thank you, you delivered what you promised'".

"After 20 years, it's not finished," he continued. "But it's pretty much what was intended to be and how lucky to have been part of this process."

Read on for an edited transcript of the interview.

Lizzie Crook: Could you reflect on your experience of working on the Ground Zero masterplan and tell me a little bit about how you approached the project?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, it was a very intense process, you know, which had so many participants. The city, the agency, the developers, the general public. It was an all-consuming process. And the only way one could do it was through a democratic process. It was not always difficult, it wasn't always easy.

It had its ups and downs, but it was always meaningful, and always... I had to be really passionate to stick to it, because the challenges were immense. Challenges were complex. So what can I say? Humbled to think of the scale of the project, but it was to pursue the work and try to work in the spirit of openness and that's what I did.

Lizzie Crook: So what were your main goals for the masterplan?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, my main goal in the masterplan was, first of all, to create a civic space, not to just be concerned with private investment, but to create a significant memorial, which brings people going to the site in an open social way. And to create as much public space as possible, which would then permit people to see the memorial as something that is crucial to the memory of the city.

But also to balance the needs of the development of over 10 million square feet of office density, with culture, and with pedestrian pleasures, and to balance memory, and the future in a very unique way.

So that was really the goal. And of course, to meet that incredible programme, which is almost like building a downtown or a whole American city, within 16 acres. But remember that, out of that 16-acre site, there are eight acres of public space, which is what my goal was. To create that sense that this is for New York, this is for people, and not only for people lucky enough to work with those offices.

Lizzie Crook: How did you prevent the site from becoming a sad space and instead make a vibrant neighbourhood?

Daniel Libeskind: It's a balance. You don't want to make New York into a sad city. You don't want to create something that is just mostly shadows and darkness. What you want to do is to create a public and social space, which speaks about the event but in a positive way.

And of course, to do that I went all the way down to the bedrock, the slurry wall, which supports the site and created a sense that this is not a two-dimensional space, that this is really a fully three-dimensional space where you can reach the place of tragedy, but also the place where you can see the rising of the foundations of New York, which still really support that site with the slurry wall.

And of course, to balance the streets, the big buildings that have hundreds of thousands of people working. There is no retail fronting the memorial. You have more quiet streets. And then of course on the other side, you have the noisy shopping streets of New York. So again on many different levels to create a composition, which stays true to what the spirit of New York is, which is a spirit of resilience, and the spirit of joy. That is, we are now in different life of this really spectacular new developmental memorial site.

Lizzie Crook: Do you think the Ground Zero masterplan has achieved its aims?

Daniel Libeskind: It definitely has achieved its aims because life has returned. After six o'clock, Wall Street was just a dark area, there was no retail there, no people living there. It was dead at night. The plaza of the Twin Towers was closed because it was too windy to walk through it.

So I created a sense of a neighbourhood by creating this composition of buildings, which are also symbolic elements, you know, the 1776-feet-tall tower number one, the fact that the buildings stood in a sort of stood in a spiral movement within the grid of New York that echos the torch of Liberty.

The fact that I brought water to the site, you know, the waterfalls, in order to really bring nature in to screen the busy streets and noise of downtown New York. Of course, exposing the slurry wall, which is no small achievement, to make people understand where they are, that this is the bedrock, this is where we are stood and where it stands still. Those are all the kind of elements.

The only anecdote that I can tell you is that when I came to the site, with all the finalist architects, many great architects, and we were on top of one of the skyscrapers next door, and somebody said, does anybody want to go to the site? I said, yes. I was the only one because we could see the site much better from a high rise office building. But I walked down there with my partner and wife Nina.

And really, my life changed as I walked down that route, 75 feet below the streets of New York. And when I touched the slurry wall, I realised really what the site was about, it wasn't about just nice buildings and traffic and all those important planning ideas, it was about deep memory.

I actually called my office, which was still in Berlin at the time, and I said, forget everything we've done, just put it in the garbage. Already a lot of models, drawings, simulations, and animations, you know, working with many experts on this project, I said, forget it.

Throw it out. It's not about that. It's about not building where the Twin Towers stood. Making it all really part of the public space of New York. And I'm really impressed how in a democratic process, this came to fruition. You know, nobody declared the site a sacred site. This was a commercial site where every square inch is worth a lot of money. But I felt that somehow it's not a piece of real estate anymore.

It's something that belongs to all of us. I was to work in a democracy, as fraught as it was, it was very fraught with many battles to fight, but I am really a great advocate and believer in democracy. I don't buy projects that are just from the top down but involve all sorts of interests. And I think it just shows that democracy does work.

Lizzie Crook: Reflecting on the event of 9/11 itself, how would you describe its impact on architecture in the US?

Daniel Libeskind: It had a huge impact in many ways. Number one, it had an impact in the sense that people understood that big projects are not only for private development, they belong to citizens. You know, I don't know what you know, the story, but the original, there was no original competition at all for Ground Zero.

It was a port authority call for good ideas that they could use, right. But it was the public that demanded what they saw, and luckily [my idea] was the one that was in the eye of the public. The public said 'we want this project' that's what we want. We don't want a typical port authority collage of ideas.

We want a project that has all these elements, symbolic elements, the great social public space, the grand memorial, the underground and so on. And so the port authority was, in a way, forced by the public to implement something that originally was not part of their agenda. So first of all, the competition showed the power of the public in determining the future of their cities. It also meant that subsequently, people in New York, were far more sensitive to what they could build, and how high should it be, and how can it respond to the context where people are living. So public participation became, I think, much, much more important than before.

Remember that Twin Towers were built without any public input, they were just sort of there. It was another era. So and also, I think it gave people a sense that architecture is important, that it is not business as usual. But architecture should have some ambition. Public space should have an ambition, it should not be just left to your technocrats and bureaucrats to determine the shape of the city.

By the way, I think the impact was on the whole world. Everything changed in architecture after that. People were no longer willing to do it as before. And I think that was sort of one of the focal points that this competition gave to the world that that architecture is important. Planning is not a private business, it should be determined by a democratic voice of all the different interests, which includes developers and agents, the people, you know, all sorts of different constituencies.

Of course, I started with their families by beginning with those who perished. I didn't start with the building, I started by speaking to people, the fathers and mothers, husbands and brothers, you know, that's what moved me. It was about people. And I think that's changed the idea that memories are important, that memory is not just an add on. But memory is a critical space in a city that must be preserved. Because without memory we would be built to a kind of amnesia.

Lizzie Crook: What was it like to speak to the families?

Daniel Libeskind: Oh my God. That was really very sad. As I said, I didn't start by going and measuring, you know, how many subway lines are necessary to go through the site, although that was part of my project, how to bring them together, and the train terminal and what to do with traffic, and how to bring the streets back.

I started with people and I spoke to them and I became friends with a number of people who lost loved ones. And I understood that this pain and this suffering is also part of the site because it happened on this ground in New York, in Manhattan. And I thought that the most important thing would be to bring the space back to focus in a positive sense, in terms of doing something that means something not just in terms of quantities or profits, but in terms of how people would feel.

And I'll never forget, a couple of people came over to me, he lost a son who was a fireman, one of the firefighters, and she lost her daughter who was a flight attendant on one of the aeroplanes. And they showed me a drawing that they had. I'll never forget the drawing, they unfolded a drawing, and I did not know what it was, it just had 1000s of little dots on it. Really, I didn't know what it was. And it was where body parts were on the site, literally hundreds of thousands.

From that time on, I realised I'm not going to treat the site... this is a site that in my mind is a spiritual sacred site, it cannot be just treated like any other site. And you cannot just build the buildings where they used to be. But I understood that. And I followed many of the families, and I was in contact with them throughout the process. And yeah, that really changed my part of it because it could have been any one of us. Who would have been in that building, either working there or delivering something or cleaning the floors or whatever. One could have been one of those 3000 people or so.

Lizzie Crook: Was there ever a feeling that 9/11 could have been the end of tall buildings?

Daniel Libeskind: Oh, yes. You know, the mayor of New York, Rudy Giuliani, just wanted low buildings. Forget it, you know, New York is a city of towers, it always has been, you know. People said after that attack, I remember, because our offices are right there, right, at the site. People said nobody will ever come back to downtown, companies will move to New Jersey, they'll move to Connecticut.

People don't want to be there anymore. It's that place. But no, it's New York, it's the spirit of New York, New York is about tall buildings. And by the way, New York has the luxury to build tall buildings. Because you know, it's a high-density city with transportation that brings people to work and to play, you know, all around.

By the way, today with a pandemic, people say the same thing. People will not work with offices anymore. Everybody will be home, it'd be remote working. But no, there's no doubt in my mind that New York, like all great cities, has its own traditions. And, you know, it's a kind of capital of the imagination and creativity and that's where people will always come and will do work and be there. Yeah, not for me, that's, you know, the suburban house with a lawn is going to replace the great powers of New York.

Lizzie Crook: How would you say 9/11 impacted skyscraper design?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, you know, one of my responsibilities [for the masterplan] was to write some new parameters for high rise buildings, to make them ecological, to introduce green technology to make sure that they minimise the carbon footprint. So it's not just the aesthetics of buildings, but really the sustainability of buildings, that is part of the buildings at Ground Zero.

And of course, that's a really huge step in a city like New York, to realise that these buildings can no longer be built, like in the old times, you know, wasteful of energy, they have to be smart buildings, they have to really be responsive to the crisis of ecology that we're going through. And we cannot afford to build buildings, like before. So that's a really, very, very much a part of it.

And by the way, you know, just as an added bonus, my parents were basically factory workers, and my father was a printer, right next to the site. And I always thought to myself, what could my parents get from this rebuilding? They never would be in those office towers. You know, they'd be on the subways, they'd be on the streets trying to work and feed their kids.

And I said, what can I give them? I can give them a sense of New York is beautiful, there is an open space or trees, there's water, there are beautiful vistas of the Hudson and the city. Council facilities, a cultural centre being built, there's a beautiful station to go to. So yes, even the symbolic elements. And of course, the northern corner has not yet been built, because it's tower number two. But I thought it would be simple to resonate with people like my parents who were just regular New Yorkers. That was part of how I thought about the site.

Lizzie Crook: Why do you think it is that people still want to build and live and work in skyscrapers?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, first of all, you know, if you don't want to consume more and more land, and keep building, out and out and out and reinforcing cars, you know, fossil fuels and so on, you have to build densely. That's why cities originated. Cities originated because people want to be together.

Everybody wants to be there to share, and improve themselves, get a better job, or learn something new. That's why people flock to cities, it's creativity. Cities have been carved, not by coincidence. The cities are probably the greatest inventions of humanity because people realise that being together, gives you something that you can never get by being, you know, in a monastery alone, somewhere far away.

So, because of that, and because of sustainability, we cannot consume land by building low buildings and eating up what's leftover of the nature we already managed to destroy. It's such a clear way. So it is a necessity. But also there's a magic to tall buildings, beyond the necessity, there is a sort of primordial sense of joy of being able to dominate the city you are in from a higher perspective.

Le Corbusier thought that the best floor to live on, buildings should not be really higher than the seventh floor because, you know, you're supposed to live on the streets. You're not in the sky. By the way, I live on the seventh floor! But the truth is that when you're in a high rise in a skyscraper, it's just so liberating in many ways. You're so... again, the mythology of being high, and the necessity of building high density, which means tall buildings. It's not about to disappear. We're not about to go backwards and you know live in three-storey houses, two-storey houses.

Lizzie Crook: What do you think architecture's role is in providing closure for victims and the families of victims of such tragic events such as 9/11?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, I think there's no doubt that architecture has a healing role. To build a beautiful space, a place where you can come to, which is a spiritual place, even in just a regular, you know, piece of the city.

But it's a spiritual space when you enter that space, you hear the waterfalls, you see that the buildings, that the great office towers really are far away from you, so that you're in the light, and not in the shadow of the towers, the towers are really of the periphery and form a horizon through which you can also the beauty of New York.

I think that provides a sense of place that, you know, you might not feel the sadness for people who lost loved ones, or the sadness of the attack that killed almost 3000 people, but you feel that there is a sense of integrity, a sense of reality, in the space, and the sense that the space speaks with its own voice.

And by the way, I don't know whether you noticed when Pope Francis came to New York, some years ago, to give his address to all religions, he chose the slurry wall, underground of the museum, to give his ecumenical message. He could have chosen Times Square, St. Patrick's Cathedral or Central Park. But I think the pope understood that this wall speaks through a world about threats, and also about liberties, about freedoms. And I think that was a very moving, moving moment when I was there.

Lizzie Crook: Are you still in touch at all with the families of the victims, or have you ever heard how they have received the site and what it means to them?

Daniel Libeskind: I can tell you that when Ground Zero first opened, when it was completed, it was completed, tower number one and so on. They invited only the families, not the public, and I was there. And so many people came to me, you know, I was anonymous, I was just walking, because they knew me from you know, pictures or they knew who I was, to thank me.

And I still remember the words people said to me: 'thank you, you delivered what you promised. What you said actually happened'. And so of course, you know, I'm a New Yorker, I live and work right next to the site like many people from that era. And I'm glad you know, before the pandemic, this is one of the most visited sites, over 20 million people come through here.

So it's one of the most visited sites, even by New Yorkers. Many people that I met said to me, you know, I live in Brooklyn, or I live uptown, and they never wanted to come back to the site, because it's such a terrible memory. And now that I came to it, it's so great. I feel so much better when I came back to it. So even sometimes New Yorkers were traumatised not to come back to the site. But people have flocked back.

And it's really, I think, a space that is attractive, that has a lot of segments of the city and of memory and also the future, because before we got set, there is all the construction, we are now building tower number five, a residential building, which is fantastic because I always thought that the programme did not contain housing.

But I always thought that that's the kind of site would be that people would live there. And so now, the fifth tower is a beautiful tower that will be also affordable, much of it will be affordable housing, which is so important. So, yeah, this is, of course, it's a site that is evolving, it's not yet finished. After 20 years, it's not finished, but it's pretty much what was intended to be and how lucky to have been part of this process.

Lizzie Crook: What does the success of the site say about the resilience of New York and New Yorkers?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, I think this place, prior to the catastrophe and prior to rebuilding, you know, lower Manhattan was not exactly a cool place to be in. It was, you know, dark skyscrapers after six.

And now, it's really one of the most exciting neighbourhoods, you know, a lot of new housing has been built. Hotels, a lot of retail, schools, a lot of people have moved to the site, a lot of great office buildings have been transformed to residential towers. So it's really, you know, it's now in a new neighbourhood, lower Manhattan is like, one of the coolest, if not the coolest neighbourhood in all of New York, for the next 30 years. So it's really, more than building skyscrapers and more than just building facilities, it's creating a space that could act as a magnet for people to live there. And, of course, by coincidence that people want to live there because there is a sense of a centre of social space that will only increase the time. I'm so lucky to live there.

Lizzie Crook: What were your main lessons or final reflections from working on this project?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, in my view, I always thought there were so many cynics and sceptics about this project. You know, they said, oh, it's gonna be all compromise, and it's all this and it's all that.

But in the end, you know, I am not impressed by the mega projects made by totalitarians. I'm impressed by what a democracy can accomplish with its kind of intense discussion, its disagreements, its strong opinions. And of course, there's no city that has stronger opinions than New York, you know these rough sort of voices. And yet in the end, the fact that this project is so much... the project that I drew the beginning, my first drawing, my intent, that the fact it was to navigate through these complex waters of a democracy shows that first of all democracy is not easy.

But it shows that democracy is the only system worth working in. And that's really my reflection because it's real, you know, what is built in the democratic spirit becomes real. The Twin Towers were never that real because they were a Robert Moses kind of planning, where nobody really participated.

The highways that were built around New York by Robert Moses, but this is something that sort of reinforced my belief that, however difficult the process was, and it was, and however many, you know, conflicts that were at the end, you know, it delivered something, which I'm very proud of, and I think the developers are proud of it.

People who are working there are proud of it, the people who suffered, the loss of their families are proud of it. People who just come by it, who are now living there, you know, it's become a part of the city. I mean, that's really, the greatest indication of working certainly could become part of a true reality and not sort of something artificial.

9/11 anniversary

This article is part of Dezeen's 9/11 anniversary series marking the 20th anniversary of the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center.

The portrait of Libeskind is by Stefan Ruiz.