Europe explores solar farms in space with Solaris programme

The European Space Agency is investigating the possibility of setting up solar arrays in space in the hope that access to 24-hour sunlight will help to overcome issues of energy intermittency on Earth.

As part of the Solaris programme, the European Space Agency (ESA) is looking into whether space-based solar power (SBSP) could meet Europe's clean energy needs as early as the 2030s to help the continent reach its net-zero targets.

It joins the space agencies of several nations including the US, China and Japan in exploring SBSP, which mostly relies on technologies that have already been proven to work here on Earth, according to the ESA.

"This is not science fiction," the space agency said. "The fundamental technologies are understood and are already being demonstrated on Earth and in space today."

Solar farms would beam down power from space

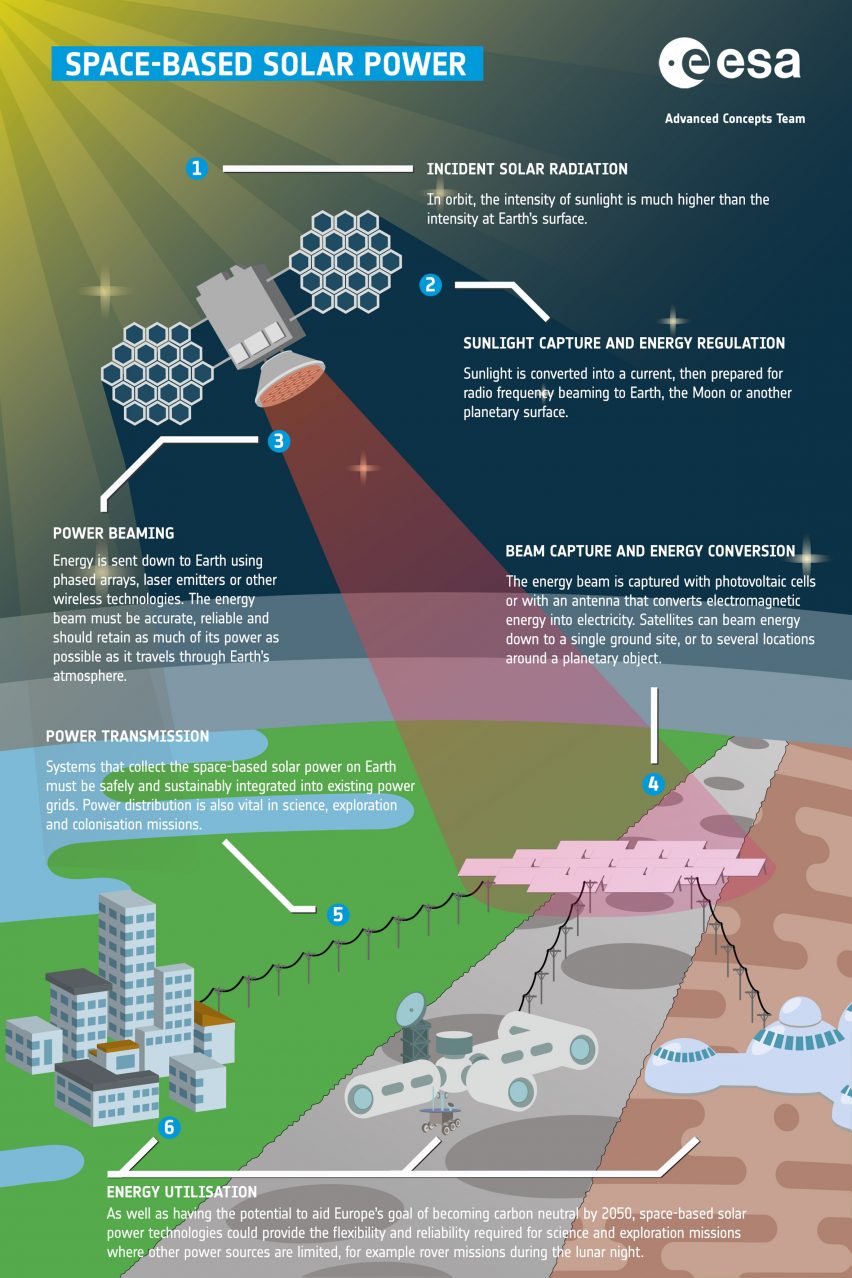

SBSP would work by capturing solar radiation in space, where the intensity of sunlight is much higher than on the Earth's surface and available 24 hours a day, with no disruptions from nightfall or cloud cover.

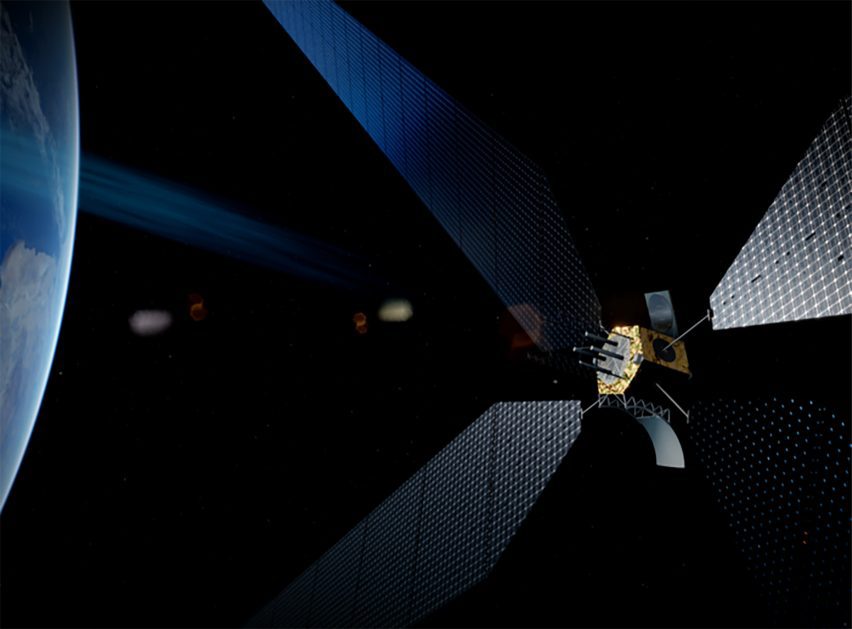

The ESA envisions there being massive Earth-orbiting solar farms, which could be launched on low-cost, reusable launchers such as the Starship currently being tested by SpaceX before being assembled in space by robots.

These huge solar arrays would collect sunlight for transmission to a receiver station on Earth in the form of either microwaves or laser beams.

The earthbound receiver stations would then use either photovoltaic cells or an antenna to capture this energy and convert it into electricity that can be delivered to the grid.

The idea for SBSP has been around since the beginning of the space race, when it was actively investigated by NASA and found to be promising.

The ESA's Solaris programme is currently in a preparatory stage, having been funded in November 2022 by the ESA Council to lay the groundwork for potentially launching a full development programme in 2025.

Energy transition "extremely difficult" without additional renewable source

The ESA says that if SBSP were to be successful, it would solve some of the key problems standing in the way of a full transition away from fossil fuels.

"Transitioning to clean energy is an urgent imperative and Europe has commmited to achieving net zero emissions by the year 2050," the ESA said in a video.

"But this will be extremely difficult if we rely only on existing renewable and low-carbon energy solutions, as intermittency of supply, pressures on land use, scalability and toxic waste limit how quickly and effectively existing energy sources can be rolled out."

The ESA is exploring SBSP as part of its Solaris programme

According to the ESA, space-based solar power provides a "continuously available, inexhaustible, sustainable and scalable source of energy" that could not only help to fight climate change but also build up energy security.

"However, there are still many engineering and policy challenges that would need to be overcome to make this ultimate energy source a reality as early as the next decade," the agency said.

Agency investigating possible risks

The ESA's Solaris investigation was greenlit after two independent cost-benefit studies – one from UK company Frazer-Nash and one from Germany's Roland Berger – which found that SBSP could provide competitively priced electricity as well as other environmental, economic and strategic benefits such as energy security.

The agency is now partnering with European industry to further assess the technical feasibility and consider other benefits and risks.

At an industry day in October 2022, ESA identified some of the key technical challenges to be solved, including how to deliver high-efficiency photovoltaic and power conversion, how to ensure accuracy in beam formation and how to deploy, assemble and maintain large-scale structures in space.

The agency is also asking organisations to assess potential risks to the health of humans, animals or plants in the vicinity of receiver stations, as well as how the beams will interact with the ionosphere, the atmosphere and the environment.

The embodied carbon of deployment and potential impacts of beam interference on aviation and ground infrastructure are further areas for investigation.

Kim Borgen, founder of space technology company Alvior, was among those present at Solaris's industry day. He told Dezeen that SBSP signalled "a paradigm shift in space".

"The reason we still burn fossil fuels for the majority of our electricity is that it is very predictable, reliable, stable and flexible," he said.

"Realistically, if we want to replace fossil fuels, we need alternative power sources with these characteristics, characteristics we only get from hydro, nuclear and fossil fuels," Borgen added. "SBSP delivers all of these characteristics."

"The science is sound, the engineering is feasible, and the economic feasibility is soon demonstrated by the upcoming Starship from SpaceX," he continued.

"Starship may make electricity from SBSP competitively priced to fossil fuels, but I assume that other novel transportation methods, such as space planes, electronic accelerators or in-orbit tethers might make the electricity cheaper than even terrestrial solar and wind."

ESA joins other agencies in new global space race

The US has been investigating SBSP on and off since 1978. In 2020, its Naval Research Laboratory tested a power-beaming satellite in space, and its air force is planning to launch a further test satellite dubbed Arachne in 2024.

Meanwhile, China has an SBSP ground station and test facilities in development and is planning to launch a demonstrator satellite in 2028 that will test out beaming on various targets and will have a 10-kilowatt power output.

Japan is also developing SBSP through its space agency JAXA and tested power beaming from a satellite to a ground receiver in 2015. The country is set to test roll-out solar panels on the International Space Station this year.

All images are courtesy of the ESA.