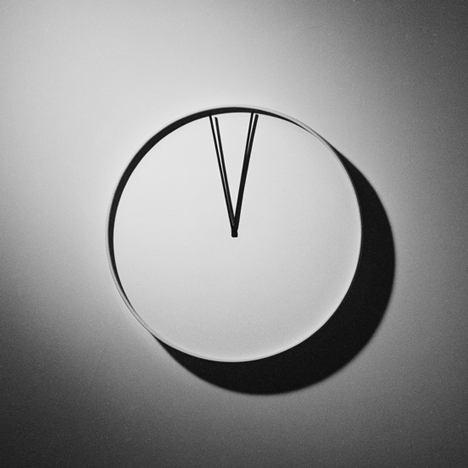

Uji wall clock moves its hands in time with your heartbeat

Designer Ivor Williams has created a clock that displays your heartbeat instead of the time (+ interview + movie).

The clock, called Uji, uses a wearable ECG sensor to record the electric activity of the heart. This information is sent wirelessly to the clock, which moves its hands backwards and forwards in time with the pulse.

Williams says the project aims to raise questions about the way wearable devices are increasingly be used to harvest "quantified self" data from individuals.

"Uji uses the same technology as wearable devices to detect the heartbeat but it doesn't use it in a very quantifiable way," Williams told Dezeen. "It uses it in a very abstract way."

Williams created the clock with Fabrica researchers interaction designer Jonathan Chomko and product designer Federico Floriani.

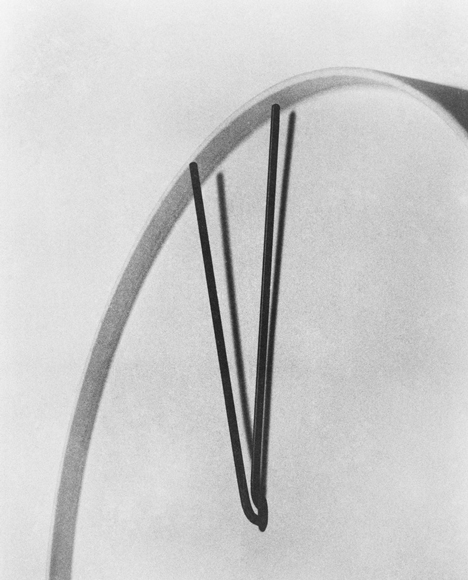

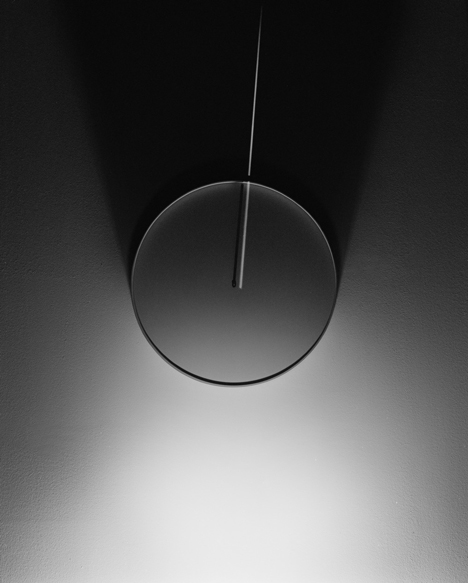

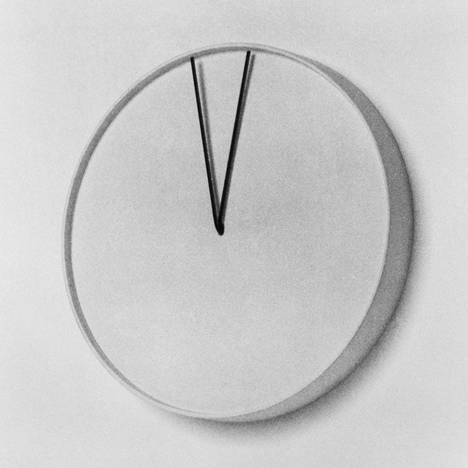

The clock is made from a single piece of handmade ceramic features two thin, black hands positioned at midnight. Instead of telling the time, the hands flicker backwards and forwards.

The "quantified self" movement, which began in California in 2007, focuses on finding ways to use technology to collect biometric data, such as measuring blood oxygen levels or tracking insulin or cortisol levels, with the aim of medical self-advancement.

"It's like the holy grail of technology, this wearable technology with this quantified self. It's like data driven enlightenment, the idea that you can know yourself," said Williams. "If we can measure all our vital signs, what's the value in that?"

He added: "One of the nice things about the clock is that is doesn't quantify, it doesn't hold," Williams explained. "It doesn't give you any information about whether you have a healthy or an unhealthy heartbeat. It's not the answer but it's one way of looking at how technology can be used to do something else."

The ethical issues of sharing data collected from wearable devices is still emerging, says Williams. "It is still unclear as to whether you own your own data, which you record through these devices. A lot of these companies are private companies so the data by Nike is held by Nike and the data by Fitbit is held by Fitbit."

Photography by Marco Zanin.

Here's an edited version of the transcript from our interview with Ivor Williams:

Grace Quah: Tell us about Uji.

Ivor Williams: Uji uses the design archetype of a wall clock. The black metal arms are connected through the back to these counterweights which are swung and motioned by electromagnets. The function of the clock itself is silent because they're electromagnets. It doesn't tick or have the sound or the traditional movement of a clock but yet it has these arms that are held at midnight and they swing back and forth.

Grace Quah: What kind of technology does Uji use?

Ivor Williams: It uses the same technology as wearables to detect the heartbeat but not in a quantifiable way. It uses it in a very abstract way. The clock isn't a way that wearables should be used, it's a way that wearables can be used. If you have a heart condition or medical issue then data collection through wearable devices have a very clear health value. For everyone else, it has a very questionable value and this technology is trying to find its role.

One of the nice things about the clock is that is doesn't quantify, it doesn't hold, it's doesn't store this information. It just restores the role of the technology to open up or to liberate this experience. It doesn't give you any information about if you have a healthy or an unhealthy heartbeat. It holds it as this expression. It's not the answer but it's one way of looking at how technology can do something else.

Grace Quah: What kind of ethical questions are raised by data collection through wearable devices?

Ivor Williams: The situation I think we'll get to in terms of designers, engineers, programmers and coders, is the responsibility of the companies, developers and the designers of how to best use this information. A lot of these companies are private companies so the data by Nike is held by Nike and the data by Fitbit is held by Fitbit. It's still unclear as to whether you own your own data, which you record through these devices. It's a problem when it comes to healthcare, in the UK the problems of losing data and the selling off of data to insurance and health companies, it presents a frightening potential.

However we all have a responsibility in that role of participation and interaction. We accept this all the time, for example this idea that we're happy for people to sell advertising to us. There's one thing for you to actively sell your data and there's another for it to be actively sold without your permission. The problem comes because health is of a different quality, it's not about consumption of goods. It's like this holy grail of technology, this wearable technology with this quantified self, it's like data driven enlightenment, the idea that you can know yourself.

We willingly accept the level of convenience and storing of information as part of being able to access different types of information. But your health is your health. It presents itself as a really personal integration with a company. With years of accumulated data about your heart, your liver function, all this has an emotional value.

Grace Quah: How do different countries approach data collection and how does this make a difference to how the technology is used?

Ivor Williams: The promise of wearable technology and data driven health is a Californian ideology. It's an American idea, that the individual can take control of their health. That's a very dangerous idea because not every system is like that. Society specific responses are needed because the technology is worldwide but the way in which companies can access and use this, including the laws, are very different.

Grace Quah: What do you think this means for the future of wearable devices and technology in healthcare?

Ivor Williams: I can imagine that maybe there will be a time where health becomes so technological that it is done through robotics and cyber-surgery. On the other hand, there will be a resurgence in deeply personal healthcare.

The role of the doctor has been pushed towards a more performance driven culture, especially in America. For example, in small town America in the 1950s, you would have the kind of doctor who would have in his case half a box of placebo because the real value of the doctor wasn't what he gave you but how he handled you and looked after you, how he knew you intimately enough.

Grace Quah: What are we missing from wearables in healthcare?

Ivor Williams: Disease and illness is as much a mental and emotional problem as much as a physical one. I think that's really interesting because that's not what this sort of technology is giving us, it is not giving us the human touch, as it were. Maybe in a way there will be that division or that divergence. Then again there's a difference between medical companies doing this and consumer electronic companies. A company that makes most of its money out of iTunes and now they're doing health.