A Model City by drdharchitects

London studio drdharchitects are exhibiting a miniature city made of clay at the Shenzhen & Hong Kong bi-city Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture.

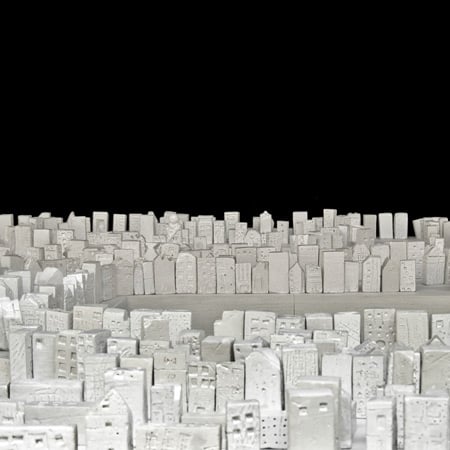

Called A Model City, the installation comprises 1500 models of buildings created in workshops with 500 school children in Shenzhen.

The children were each given a clay block with the proportions of a brick and asked to decorate it with windows and doors.

Each model house was inscribed with a code on the base and coated in a white glaze before it was positioned on a white felt grid, laid out by the children.

The biennale began on Sunday 6 December and continues until 23 January 2010.

More about drdharchitects on Dezeen: Bodø Kulturhus and Library

Here's some text from drdharchitects:

--

A ‘Model City’ – drdharchitects

2009 Shenzhen and Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism \ Architecture

Our proposal for the Shenzhen and Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism \ Architecture seeks to address the individual and collective lives of the inhabitants, and future inhabitants, of the World’s big cities. This seems of particular relevance given the extraordinary and rapid growth of Chinese cities like Shenzhen, as the country goes through a dramatic process of urbanisation. The project focuses on the physical city which most of us actually occupy. Rather than the buildings that become symbolic of a city’s individuality, it considers those anonymous and generic structures that make up the fabric of everyday life and which, as a result of increasingly universalised processes of procurement, seem to characterise the urban hinterland of metropolitan life, the world over.

With the help of local school children from Shenzhen we proposed the creation of a miniature city, made of clay. We wanted to engage local school children in imagining their own city. The process started by asking them to think about their home, through building a collection of miniature clay houses. We asked them a series of questions such as where an entrance or window might be; how these played a part in defining the overall appearance of their buildings and how it might speak to its neighbours. It concluded by asking them to consider the individual house as part of the collective city, how it might be laid out, its patterns and the relationships between things.

Ten workshops were organised in local schools across Shenzhen where 500 children participated in the making of the clay houses. Repetitive clay blocks based on the proportions of western bricks were manufactured by a local pottery school, YoYo Workshop in three sizes using traditional techniques. Smaller blocks for younger children and larger blocks for older ones. Each block was interpreted as either long and low or taller and more tower-like. Each child used wooden clay stamps and tools to decorate their houses. Collectively, the 1500 buildings produced recall a latterday terracotta army for a new China.

The houses were painted with a white glaze giving an “ivory white” appearance that reinforced the collective identity of the model city. Through decorating and the firing process each house became more singular and individual as subtle deformations occurred. Each child was photographed with their finished house which contained a code inscribed on its base as a record.

The houses sit on a surface of white felt squares representing the grid of the contemporary city on which the individual houses are placed. A workshop on site allowed the children to plan out their model city. Long boulevards, public squares, crescents and wide open spaces represent ideas about the way the city could be laid out. Alongside the model city an atlas of portrait photographs of every child with their houses was hung from a wall, relating the anonymous sea of houses to a particular individual.

The model city could have many meanings; it might suggest either an absence or the potential for craft in the making of the contemporary city. The ivory white appearance highlights the anonymous nature of cities as the background within which life exists. On closer inspection however, the variations in tone and form that result from the traditional process of firing used, alongside the subtle impressions of window openings and patterns inscribed in the facades by the children, offer each building an expression of individuality and identity. In doing so, perhaps it suggests a reconsideration of the values that we use both to plan and to reflect upon our urban environments. With the help of the children of Shenzhen, our exhibit seeks to critique and explore the delicate, but necessary balance between the universal and the particular.