Intifada by Carlos No

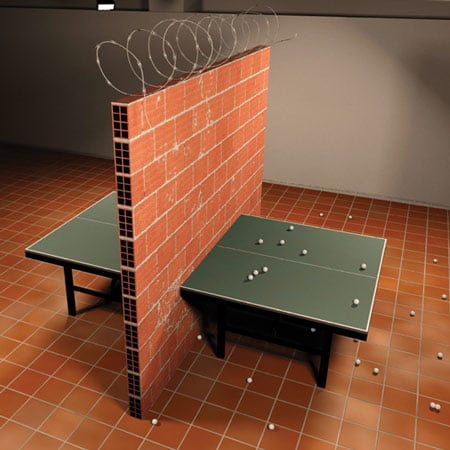

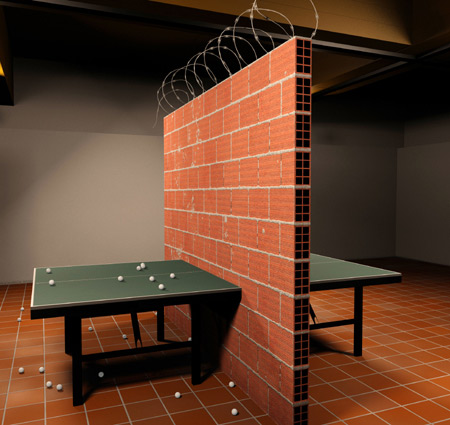

A ping-pong table divided by a brick wall by Portuguese artist Carlos No is on show at the Raiano Cultural Centre in Idanha-a-Nova, Portugal.

Called Intifada, the installation is topped with barbed wire.

“Intifada is a site-specific installation whose theme focuses the problematic of the physical boundaries," says No. "It could be seen as a solution of self-defense or, in other point of view, as an excuse or justification for segregation. It is a work who also talks about intolerance and lack of communication, oppression and abuse of power, questioning concepts as Territory, Frontiers and Exclusion."

The following information is from the gallery:

“Intifada”, or the many ways of seeing.

The visitor’s first contact is with the Title. Condensed into a single word, Carlos No’s installation precedes itself, establishes itself as a concept prior to being seen. The reason for this significant unfolding derives from the iconic character of the word, from the verbal enunciation which causes an immediate stimulus, triggering images and memory. An Arabic word, westernised in its spelling, “Intifada” thus pronounced and translated can mean shudder, shaking off or uprising; but also awakening or the stone-throwing uprising that refers to the conflict which unfolds in the Middle-East.Without needing to pick up a dictionary, we all know it. We have known it for years. There is a durability that permeates the concept, rendering it with a quotidian edge, newspaper headlines, the opening of television newscasts. One could ignore its true meaning and yet still understand its act, the almost daily gesture, the consequences of a difficultly negotiated coexistence between Israelis and Palestinians. History places the First Intifada in the late 1980s, more specifically in December 1987, when some refugees in the Jabalia camp, in Gaza, began an uprising against the presence of the Israeli Defense Forces by throwing stones, which quickly spread to the populations of the rest of the Occupied Territories.

Other similar movements have followed throughout the years, in waves and lulls awash in conflict. Form of protest, urge to expel in cyclical actions with no end in sight, in the incommunicability of the belligerents, in the inability of reaching a peace agreement. But this circumstance is imbued with the long temporality of a coexistence that is difficult to manage, in a territory to which peoples of different religions feel to belong. If the word triggers the memory, it associates it with the complexity of such a context and a wide array of images which are embodied in the vision each visitor holds on the issue. All of this is what is taken into account when one accepts the challenge set forth by Carlos No’s work. The meaning of “Intifada” (but above all the critical and reflective assumption of its existence, collectively thought) achieves form in an objectual space.

The artist re-contextualises the terminology associating it with, not the documental crudity of images taken from reality, but the metaphorical vision of a theatre of war conceived as a cognitive instrument of identity and civilisation. The core essence of that setting: a ping-pong table and a room entirely turned into a playing field. However the visitor’s first contact with Carlos No’s installation might not be with the Title. It may be by way of an unreflected entrance into the space which was devised by the artist as a games room which has been stripped of its main meaning, a rustic, ludic structure that dismantles the notions of evasion and sport, which de-contextualises the objects from their common system of appropriation, that reinvents and recomposes them in an absurd plot which gives rise to surprise and restlessness in the visitor. In the centre of the room stands a ping-pong table which, in place of a net, has been divided into two halves by a very high brick wall, topped by barbed wire that heightens a feeling of insurmountabilty.

There arises in the spectator the curiosity of seeing the other side, the place which one is forbidden to see and be in, as if one had discovered Lewis Carrol’s charade in the passage to the other side of the looking-glass. In this wonderland that comprises this side and the other side, both the space and the visitor’s steps are divided into two. On the other side of the wall, a great number of white cellulose balls are spread over the table and floor, recalling a failed game, a counter-game, a deaf monologue exercised without the desired response, facing the wall. Seen together, both halves are prolonged through the wall and deny each other the possibility of a relationship negotiated by way of rules, established and dealt with in freedom by both sides.

Once acquainted with the title of Carlos No’s installation, in the fertile interval that lies between what has been seen and read, one confirms the familiar strangeness in light of Man’s conflicts. One knows there is a wall in the West Bank, that the understanding between peoples and religions has been impossible, that there are lacerating blasts and silences on both sides, hollow gestures. More than a mere reference to a line of separation, Carlos No renders this idea of border as a physical and visually symbolical reality. Any way of overcoming it becomes as absurd as a ping-pong ball played against a brick and concrete wall.

The conflicts in the Middle East had already been pivotal to the conception of earlier pieces, such as “Montes Golan” (Golan Heights), a sculptural object crafted by the artist from a cracked butcher’s block, both ends of that involuntary laceration marked by two miniature flags of Israel and Syria. But one can say that a broader thematic regarding the identity of peoples, their transhumance and their acts of conflict or disregard for common human rights has been quite central to Carlos No’s body of work.In the paintings which compose the 2002 series“Histórias Infantis” (Childhood Tales), the emergence of that same nonsensical strangeness derives from the recourse to the childishness of fairy tales, whose texts are written on the canvasses, and the harshness of the images of child- soldiers who share that space with them. This immobilisation of dissonant discourses, of signifier dualities by continuity or disarticulation worked, just like now in Intifada, as an effectual creative strategy.

By recovering the idea of play as a territory of reflection, denunciation and protest – such as in the piece “Área Desminada” (Cleared of Mines), a table football set with amputee players in reference to the issue of the use of anti- personnel mines in Africa – Carlos No visually takes on the heritage of studies such as those carried out by Johan Huizinga, Roger Caillois or Norbert Elias who evaluated the notion of play as a symbolical system, essential for the knowledge and development of the processes of civility. But most of all he configures his artistic and individual practice as a sensitive and actively committed platform in the face of a world of expectations and small conquests.

See also:

.

|

|

|

| Ron Arad plays ping-pong |

Lace Fence by Demakersvan |

Screens at the boundary of a Tokyo property |