Leonardo's Last Supper by Peter Greenaway

Film maker Peter Greenaway will create a multimedia event involving Leonardo da Vinci's painting The Last Supper, as part of the cultural programme of this year's Salone Internazionale del Mobile (international furniture fair) in Milan in April.

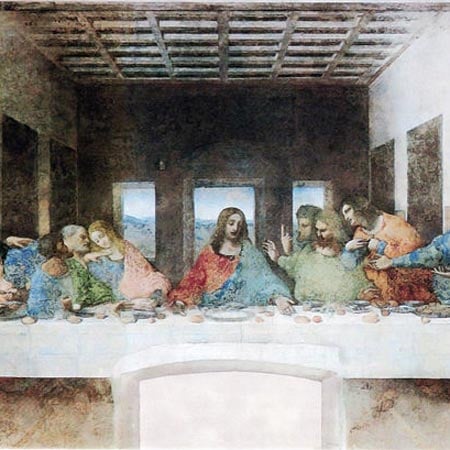

Greenaway (above) has been given unprecedented access to Leonardo's original artwork (below), which is painted on the wall of the refectory of the Santa Maria delle Grazie Church in Milan, and which will be brought to life during a series of live performances involving light projections and sound starting on 16 April, the day before the furniture fair opens. The project is titled Leonardo's Last Supper.

In addition, a full-scale clone of the painting will be presented at the Palazzo Reale in the centre of Milan, which will serve as the focus for a second identical series of events to allow a larger number of people to experience the performance.

Cosmit, the parent company of the Salone Internazionale del Mobile, announced the project at a press conference in London on Thursday, where Dezeen editor-in-chief Marcus Fairs (below, left) chaired a discussion with Greenaway and his collaborator, Franco Laera of Change Performing Arts.

Below is a full transcript of the discussion, followed by a press release about the project. The photos shown here were taken during the discussion.

--

Transcript of discussion at Cosmit Design Forum, Royal Festival Hall, London, February 14 2008.

Speakers:

MARCUS FAIRS (chair), editor, Dezeen [www.dezeen.com]

PETER GREENAWAY [www.petergreenawayevents.com]

FRANCO LAERA, president, Change Performing Arts [www.changeperformingarts.com]

The discussion was preceded by an introduction by ROSARIO MESSINA, president of Cosmit [www.cosmit.it]

MARCUS FAIRS: Thank you Rosario. My name is Marcus Fairs and, as Rosario [Messina, president of Cosmit] was explaining, alongside the furniture fair in Milan this April is a fairly major cultural event. The key protagonist is sitting here on my left, Peter Greenaway, best known in this country as a film maker but Peter says he’s better known on the continent as a museum curator. But also, as you’ll hear when we start to talk about this particular project, he’s really sort of pioneering new modes of cultural expression and new artistic forms. In fact he said to me when we were having coffee earlier that he thinks that cinema in its current state is dead and that perhaps this project that we’re going to talk about is one of the ways of exploring what could happen beyond cinema as we see it.

Also we have Franco Laera who’s been collaborating with Peter for a number of years now on a number of projects. He’s the producer and artistic director of this particular project and he runs a company called Change Performing Arts based in Milan.

So, I think we’ll just get straight into it. Peter can you tell us what are you doing in Milan that involves one of the most famous artworks on the planet?

PETER GREENAWAY: Well, I suppose, an act of some significance which some people might regard as blasphemy. The work I suppose is still seen almost as an icon of pilgrimage so it has all sorts of significances which are not purely aesthetic but represent certainly to an Italian audience and a world audience something I suppose of an apotheosis and the notions that we would have about the responsibility of the painter.

If I could give you something of a back-story: 2006 saw the celebration of Rembrandt van Rijn. He was born in 1606, so [it was the] four hundredth birthday. If you go around the world and ask people who their most famous knowledgeable attitude is towards the notion of the Dutch, who is the most famous Dutch man or woman that they can think of, they will probably come up with two names and both of them will be Christian names - an extraordinary compliment - one is Vincent and the other is Rembrandt. And the third down the list I suppose is a certain rather famous local footballer who is extremely well known in Spain and the Canary Islands but maybe is not perhaps so well known anywhere else.

The notion then that there’s an amazing tradition of painting and notions of visual representations that we’re all familiar with in terms of Dutch painting. De Volkskrant, which is the major newspaper, at the time (roundabout June) said ‘the Dutch have the audacity to give Greenaway Rembrandt’s The Night Watch to play with’; an act of extreme arrogance and maybe some notion of folly. I’ve now been living, I suppose, in Holland for about twelve years and I’ve had extraordinary opportunities to do all sorts of things which somehow or other are related to what I would describe as visual literacy. The idea would be to see if we can make connections between eight thousand years of painting history and one hundred and twelve years of cinema. To the Dutch when I say the English play with things of course I suspect you, predominantly I’m sure, would understand the notion that the English play very seriously with things. I suppose the English have invented most of the world’s games. They don’t necessarily play them very well any more but that notion of serious ludic pursuits, I’m sure, is very familiar to all of us.

So the idea then was to re-invest some excitement in this extraordinary painting. Some people say it’s the fourth most famous painting in the world. Number one: Mona Lisa, number two: Last Supper, number three: Michael Angelo’s ceiling in the Sistine, number four: Rembrandt’s The Night Watch. Maybe an awful lot of people know it from biscuit tins and t-shirts but I’m sure there is somehow, curiously, historical consensus memory about this extraordinary painting.

So obviously these things can’t be done alone and my major collaborator is sitting here in the front of the audience: Reinier van Brummelen. A long, long collaboration of cinematic representations. We’ve made many, many films together and many, many other associations.

So we obviously approached this extraordinary icon of Dutch and world art with some trepidation but if I say to you we burnt it, we flooded it and we covered it in blood, and if tomorrow morning you want to go and catch the train to Amsterdam you will still find it there totally untouched.

First of all I think there is a particular, shall we say, pragmatic and practical attitude towards the notion of cultural artefacts like paintings by the Dutch which is peculiarly very lithic.

I think we can safely say the Dutch don’t genuflect in front of their works of art, however serious they might be. And I think they’re very, very keen to make sure that ‘the general public’ (I’m never quite sure who ‘the general public’ is but I’m sure we can make some agreement about that) needs to be in the business, certainly after a very sophisticated visual representative world/the world after the digital revolution, to have some understanding of where all this has come from.

So we projected on the panting. Not a facsimile, not a clone; we actually projected on the real painting.

There’s an interesting story about The Night Watch: Just after the Second World War the Americans were the Marshall Plan, pumping huge amounts of money into Europe, so most of the smaller countries like Holland soon ran up an enormous national debt with huge interest payments. So I think by probably about 1947 to 1948 the Dutch were in enormous hock to America and the incumbent American president said ‘ok, we will forgive you that debt and we’ll wipe it completely away if you give us Rembrandt’s The Night Watch.’ Happily, happily, happily: no. There was no way that was going to happen. Eventually I suppose due to the economic miracle that took place in the early fifties Holland was eventually able to pay that debt.

But that’s another way to make a demonstration of how very, very important this painting is. Its significance is, let me repeat, not only for Holland but for the whole European notion of what we would value in terms of the painting cultural artefact.

The exhibition went on for three months, six thousand people saw it every day and I think we had both a general audience but a very well informed audience. I also ought to say maybe there is a certain cultural crisis in the world at the moment about cultural tourism. Cultural tourism is falling of in Europe. I think Italy reckon there’s an eighteen percent fall in the last five years. It’s not necessarily that foreign foreigners, that is to say people from Japan and America are not going to visit these cultural artefacts certainly in Italy, but people at home so for example in Venice, Venetians, Italians in general are not looking at their heritage. So it’s in a curious way that what we’re doing which I think takes the expectation of every single one of us, now familiar with very sophisticated means of visual representation, represented of course by great I suppose practitioners - let’s mention Hollywood, let’s mention California - but also the whole phenomenon that now makes the business of seeing and looking very apposite and very real time; very much in our pockets, on our cell phones on all the laptops we use; levels of sophistication that almost by osmosis we don’t necessarily be particularly conscious of. But bring these to bear to all the major landmarks I suppose of European western history.

I have to say that the activity was so successful that we generated the possibility almost of making a wish list of all those paintings which we would like to make a dialogue with in terms of contemporary activity and contemporary technology.

Of course we’re very proud after having tackled shall we say Rembrandt and The Night Watch now to be able to do this with this extraordinary painting. A painting that, I suppose, ever since it was created, because Leonardo da Vinci was an investigator, already had its own inbuilt sense of corrosion. He experimented with new media and new methods. I think virtually as soon as the painting was completed it began to decay. And many of you might know it’s in a very, very sad state, not particularly helped by the British of course who bombed it during the Second World War.

That sense of decay and that sense of historical temporality which would be related to a work of art we also want to build into our proposals.

But our long list now of… I don’t quite know what to call them; I suppose the clumsy word is installation which means everything but also means nothing at all… would be brought to bear. They have presented the possibility of us tackling the famous Velasquez Las Meninas in the Museo del Prado. We’re going to tackle Picasso’s Guernica which we’re going to obtain from the Reina Sofia and take it back to the Guggenheim in Bilbao. There’s a famous painting by Veronese in the Louvre called The Wedding at Cana. We’re going to tackle Monet’s Water Lillies in L’Orangerie in the Tuileries gardens. There’s a Seurat in Chicago, a Jackson Pollock in the Museum of Modern Art, New York and - and I never ever thought this was possible - we hope to be able to start long drawn out diplomacy to tackle Michelangelo’s The Last Judgement in the Vatican.

So, important stepping stone for us is to be associated because I think a lot of eyes are going to be watching. What we’re going to do here is the investigation of the notion of cinema meets painting: after eight thousand years, the dialogue that can be perpetuated to examine the social, political, aesthetic and of course spiritual value of these major benchmark paintings which of course, even thanks to Dan Brown, everybody now thoroughly ought to know about.

So we start this project probably in a few weeks time and we hope to open it exactly on Good Friday and what better day to tackle the last supper than on Good Friday.

So I again like to take this platform to suggest our thanks. I know that an enormous amount of diplomacy’s been going on. We have a lot of detractors, we have a lot of people saying ‘no you shouldn’t do this thing, you shouldn’t turn Leonardo da Vinci into a film, however sophisticated,’ but I think that sense of possible aesthetic combat is also very, very exciting

It’s been suggested that I believe cinema is dead. I’m not going to apologise for that statement. I certainly think that cinema is brain dead but I still believe the notion of a screen is omnipotent. There are probably at least, I don’t know, four cameras in here watching all of you; you’re probably all on a screen now so I would certainly champion, still with a slight smile on my face, that the screen on the mobile phone in my pocket is now going to be far more important than anything in Leicester square or Piccadilly Circus. I think you know that. I certainly know that. It takes some time to get rid of our nostalgic ideas about some notion of cinema that our parents and forefathers believed in but the idea of the screen and notions of visual literacy I’m sure are deeply, deeply on the agenda.

One idea which really fills me with enormous delight: it’s now generally regarded, is it not, that for the last eight thousand years the people who are responsible to be the gate keepers of our aesthetic appreciation are basically the text makers. They’ve been in control for so god dam long. But now thanks to the digital revolution there is a long, slow sea change. And before long if you’re an image master, by god, you’re going to be far more powerful than those text masters of the past.

MF: So we’re talking about Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, which is painted directly onto the wall of the refectory in the Santa Maria della Grazie church in Milan. So once your project is installed what will the visitor actually see when they go to experience your installation? What will happen?

PG: Well most of the paintings of the world, of course, have been removed from their site of manufacture. This particular painting was always intended to be at one end of a refectory eating place for the Dominican monks roundabout, I suppose, from about 1400 up until 1550’s / 1560’s. Very much associated of course with all the secular powers so it was an act again of commission and status as well as a powerful image for Christianity. And Leonardo again, without wishing in any way to give an art history lesson, created a situation where the painting in a sense was an extension of a physical architectural space. An exercise as you can see very obviously in terms of perspective: these lines are intimately related to the circumstances.

So we will not only change the lighting scheme, create dawn and noon and midnight, we will examine the careful cosmology which exists symbolically on this table, we will be able to identify all the particular significances of all the thirty people represented here, we’re going to interview every single one of the apostles to see what they thought about the event, we’re going to relate it to all the other paintings that Leonardo made about the life of Christ to show that we don’t exactly know Leonardo da Vinci’s personal opinions about religious belief, to show him deeply, deeply as a highly spiritual man and to indicate why this painting has somehow touched notions of spirituality since it was ever painted.

The other fascination is (which is related to a particular I suppose social condition) because the painting is so fragile it’s been put up for very restricted viewing.

So I think the figure is that only 25 people are allowed to look at it at any one time. You virtually have to pass through a dust lock to get in, because the actual painting surface itself is so very, very fragile. And what Franco here has organised for us is to open up this possibility by contacting and collaborating with some extraordinary new technology, which if I pronounce to you the word ‘clone’ now first of all you’re going to groan and secondly you’re going to be very suspicious. But the actual technology we’ve involved here I assure you is amazingly sophisticated which virtually in twenty first century terms recreates the painting. Maybe I should ask Franco to explain a bit further.

MF: Franco first, you are going to clone the last supper, right?

FRANCO LAERA: We should say that it was really I think the most challenging thing I’ve done in my life. I mean for one year I’ve been talking to all the scholars, all the attendants, all the people responsible for this place which is really the most difficult place to get in and as Peter said sometimes it’s even difficult for the people living in Milan. My office is just across the street from Last Supper, just by chance, and I can see every day lines of Japanese people just waiting to enter the last supper because they can book the ticket maybe two years in advance. So you can enter this place only at that time in the specific moment and you can stay only fifteen minutes and only twenty five people every time.

So it was in the beginning really even in my mind impossible to think that this could be possible. When I saw the first time the Rembrandt I was so impressed I said to Peter “We have to do something in Italy it’s such a great country. We have million masterpieces so you have to think and you have to find a way to make this kind of event also in Italy.” And he said “are you sure that you want to do it?”

“What are you saying? You did something incredible”

“I mean really, are you really sure?”

“Yes” I said, “why are you asking me?”

“Ok, I want to do Last Supper.”

I said “No thank you. Thank you but no. It’s impossible”. Because really even now if we think about this it looks something impossible. Even I think thanks to the fascination of the work, this incredible work that Peter ad Reinier have done in the Rijksmuseum - and I hope we have a chance to look at it later on - I was able to let’s say convince or better to create partisans to this enterprise and then, not touching at all the schedule of the visits of the visitors who have booked the tickets two years in advance, we will take a specific section of the day between seven thirty and eleven thirty pm and then using the same kind of format so twenty five people every time; every group will have twenty minutes to get inside the last supper. In the first section people will have chance to look at the painting as anyone can see it today so with the museum type light which according to my personal experience is not really the best possible light but they are really very difficult in accepting to have an higher light pollution. They are very concerned that this can modify the very fragile pigments of the painting.

So then I imagine that Peter can say better but the usual light will be dimmed off then there will be the central part which will be event created specifically. Then there will be a third section where people will see again the normal light on the painting.

MF: How long will the event last?

FL: It only will be twenty minutes. Usually they are allowed to stay for fifteen minutes but for our event of the section every look will be twenty minutes.

MF: Of the actual projection?

FL: If you imagine twenty five people every twenty minutes means seventy five people every hour. For three hours… I mean the calculation is very easy. We can do this just for two months, maybe three months. So still we are a small number of people can attend this event.

And then we started with how to say also thanks to the fact that we have as our partisan Cosmit and this Milan design week, the furniture fair and we have three hundred thousand people in town during the week so how we can solve the matter of showing this masterpiece to a larger number of people. And then the idea of the clone came up. We call it clone because we cannot say copy we cannot say photo is not, it will be because not existing we are doing it, it will be the result of the balanced combination between high technology I mean the company has created the most heavy photo file in the world which is more than twenty five or twenty gigga having in one photo so in one picture and people can access this also through internet is existing already it already is possible to access, this photo has a resolution of more than 500 dpi in the size 1:1 so it’s the most heavy photo existing in the world.

So using this technology with this detail combined with the capacity of very good restorers we will print in different sections the entire last supper. It will be then reconstructed on site and then I mean the print will be done in different layers with the same kind of pigment and the background will be exactly the same background as Leonardo has used to paint the Last Supper. We say painted because people believe that this is a fresco. It is not a fresco and that’s the reason why it’s so deteriorated. It’s not a fresco. He did it with the technology and pigments of painting but on a wall which is plaster. Just fifty years after Rosari was writing in his text that the painting was already gone I mean nobody could see it.

So we have used also a 3d model of the refectory. So what we call the clone will be really another piece of work, another piece of art where many people are collaborating just to get this extraordinary… some would call it facsimile, I prefer to use the word clone. But this will give us the chance to install this artwork in the centre of Milan and of course in this case we will not have all the restrictions that we have in the Refectory.

Of course this will not be done in a very …. Not reproducing exactly the refectory in the Santa Maria della Grazie which is the church where still it is but trying to rebuild a different situation that can give also the chance to Peter and Reinier to use very advanced technology in high resolution projection.

MF: And that’s going to be in Palazzo Reale.

FL: In Palazzo Reale, yes. And of course this will, I mean we can have a lot of people in every time but with absolutely the same structure. It will be twenty minutes but to look, whereas it could be twenty five, it could be one hundred and fifty so the number could be much larger.

MF: And in order to understand what you’re going to do with the painting (because effectively you’re going to project light onto it and play sound to bring the painting to life) maybe now’s a good time to show the short video we have of The Night Watch: the project that Peter did with Rembrandt’s painting in Amsterdam.

PG: And if I could just say by no means a justification but what you’re going to look at now is a timid little DVD; the screen is small, the resolution of the colours… you know how the language goes. But imagine what we are about to see projected on the real, iconic original. So maybe we could project. Here we come. It has a sound track so let’s make it nice and loud as well please.

DVD plays

MF: In Rembrandt’s The Night Watch Peter there’s a narrative, isn’t there? There’s a kind of murder mystery or there’s a suggestion of conspiracy and I know that in your movie you touched upon that. But this thing that we’ve just seen hasn’t really gone into that, it just kind of unlocks various layers of the picture, you’re not really kind of, there’s no real narrative in that piece is there?

PG: No. In the Rijksmuseum indeed we did make a presentation of a conspiracy theory that Rembrandt paints this painting as a s’accuse, accusation, against the local oligarchy of Amsterdam of the 1620’s which holds a conspiracy and a murder. It’s a little difficult to see of course, we can’t show you in the video but if you went to the original you would see that a gun is going off amongst this mêlée of thirty four people

MF: Can we bring back up the first frame of the movie? Is that possible?

PG: But I think that even if you were to bring it up because of the manipulation of shadow it in some senses has to be pointed out.

But traditionally again I suppose, rather like the da Vinci, The Night Watch has been on public show for 400 years so an awful lot of people have seen this film and commentated on it and there’s a general feeling that there are fifty mysteries in this painting which don’t necessarily hang together to make a satisfactory explanation of what really Rembrandt was trying to do. And there’s an even greater mystery I suppose which is related to Rembrandt’s life. He was a sort of Mick Jagger/Bill Gates figure at the beginning of his career: incredibly wealthy, was earning by selling one painting what the average tradesman would earn in one year and also he was highly desirable company. He was, you know, you wanted to go and drink with him in the nightclub. He painted all the chattering classes. But then in 1642 when he painted this painting there seems to be an amazing collapse in his career and he’d lost everything so within fifteen years he was living in a one up two down little suburban allotment house at the bad end of Amsterdam. And it’s always been very, very difficult to explain why this happened. And our theory which we presented indeed in the Rijksmuseum and which is also the substance of this feature film that’s now opening in Europe called Nightwatching is to explain that this is Rembrandt’s s’accuse. He was bold enough, arrogant enough to actually play a David and Goliath game by making an accusation of all these rich fat bourgeois cats who were organising and controlling the powerbase of Amsterdam at that time; to actually accuse them to their faces. To paint within the very painting they’d commissioned from him a massive accusation. Working out all the clues, far too many and too complicated to tell you now, but please go and see the film and you’ll understand, to explain why that is happening there, why that man is wearing this, why that shadow is there, why are there thirteen pikes, why does this man look like Judas Iscariot, etc etc etc.

In order to make a demonstration that eventually all these thirty for people - you must remember Murder on the Orient Express where everybody was a victim or everybody was associated - well imagine this is Rembrandt’s Murder on the Orient Express. So all these people connive to create a situation for their own financial advancement, which is actually deeply involved with Charles the First and his parliament and the beginnings of the civil war in this country. Which also helps to explain a big revenge theory: all these guys got together to destroy Rembrandt. The explanation why he lost his fortune, why all the women in his life were abused, why all his creditors turned in the money etc etc etc.

So it is - you’re right - we have created a scenario based upon I suppose conspiracy theory to make a grand visual investigation of what’s significant about this painting. But here I suppose there are other devices. I said already that we flooded the painting, we burnt it and we covered it in blood. To all you visitors of Amsterdam you probably know the ubiquitous sign of the three crosses. All over Amsterdam there are three crosses. They are meant to represent the three crosses of Saint Anthony, and in English that means Flood, the Flee and Fire. Flee is a little problematical but it represents the plague. Any you pray to Saint Anthony to “please don’t burn our city” (it’s made of wood before 1600), “please don’t flood our city” (I live in Amsterdam and my basement is two and a half metres below sea level) and “don’t visit us again with the plague.” It’s the first big city on the Atlantic sea border, has enormous contacts with the Far East. Every three to five years the plague comes round yet again and a least I suppose ten to twenty percent of the Amsterdam population perishes. So we’ve instituted those notions: we, as you can see, we have flooded so to speak with a huge rainstorm, we have burnt the city by inference and also at the beginning we’ve actually covered the ground with blood as an indication of the notions of plague.

But on a much simpler level if you’re looking for a straight, red line narrative it’s a day in the life of. The film begins with the cock crow and it ends with the midnight bell. So you have in a sense an opportunity, an excuse, to use all different types of lighting scheme and at the end here is a little coder to make a demonstration of how Rembrandt has devised the picture in a series of basically three levels.

I think one of the other sort of hypertexts of the film is in a curious way that Rembrandt is not a painter at all: he’s really a man of the theatre. And there’s a way in which this, with it shallow stage, its presentation of characters playing with costume it’s whole mis en seine, is really a frozen moment of early seventeenth century theatre. Most of that theatre in fact was imported from England. There’s lots of references to the works of Webster and Ford being played on the post Calvinist, post Puritanical stage in Amsterdam in the 1620’s and 1630’s.

So those are our ways in which we can find I suppose the most primitive of narratives to be relative, to give you fairly true knowledge the temporality of the notion of giving the static image a sense of time, and certainly a soundtrack, and to make it a presentation of an exemplum of this high Baroque notions of artificial light and drama of the theatre. I would argue the cinema was not invented by the Lumier brothers in 1895 on the twenty sixth of December, but was actually created here by people like Rembrandt and his amazing artificial light painting contemporaries. So you’d have say Caravaggio, Velázquez, Rubens and Rembrandt. So these are the people who invented cinema, that’s my thesis anyway, at the very beginning of the seventeenth century.

MF: And with the Last Supper, there’s few paintings in the world that have been subjected to so many conspiracy theories and readings and you mentioned Dan Brown I mean most people’s understanding of the work of Da Vinci has now come through the cipher of The Da Vinci Code and the whole novel, so what can you add to that painting? What can you undo that Dan Brown did to that painting? How are you going to treat that painting in comparison to what you did with the Rembrandt?

PG: Well obviously Da Vinci watchers over four hundred and fifty years have offered many, many theories and Dan Brown’s only the last one and after all, as we all know, he copied that and borrowed that from other people too. So I think you know, first of all I have nothing against… I don’t want to be culturally snobbish about Dan Brown or the Da Vinci Code. It’s another way to get people to look; look, look, look, look: this is a fascinating object. Why? Why? Is it this way? Is it that way?

I’ve always argued there’s no such thing as history, there are only historians. There’s no such thing as art history there are only art historians. In the curious way Gibbon writing about The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire is no more valid than Ridley Scott making Gladiator. And there’s a curious way, you all know and I know, most people learn their history from the cinema. But why shouldn’t we actually have interpretations. We might find them vulgar. We might find them uninformed. We might even find them mischievous but at least it does something very, very profound: it gets you to look at the damn thing again. And that’s very, very important.

MF: And is that, ultimately, the purpose of this: to get people to look at art and think about art?

PG: Well I sincerely believe we’re text merchants. Across all the language barriers we’re very sophisticated about handing words but most people, I have to of course to except you because you’ve all had a design education, haven’t you? Haven’t you? Haven’t you? Haven’t you? You’ve all been to art school; you’ve all been to design college; you’ve all been trained. But most people are visually illiterate. Because it’s the way we have devised the major means of communication. That’s why we’ve got such a ridiculously stupid cinema. You know, it’s not an image based phenomenon; it’s a text based phenomenon. Every time you see a film you can see the director following the text: tragedy, tragedy and we’ve had to live with that for one hundred and twelve years. I feel very, very pessimistic, as you can tell, about the notions of where cinema currently is but I do have an enormous amount of enthusiasm about what happens next. Because I do think that the digital revolution in a curious way has wiped the slate clean and we can begin again.

So here’s an opportunity to encourage the notion of visual investigation; to bring to the fore this very, very great language which we all share about the forms and the fascinations and the successes of the notions of visual communication.

MF: So, the Last Supper: what are the things and the stories within the painting that you would bring out? And also with Rembrandt you’ve then made a feature film. Will you be making a feature film from this?

PG: No. No, I shall be going on forever and forever with this so called “illustrating all the famous paintings of all time”. Well I don’t think there’s any point in doing that.

MF: I was going to ask you how’re you going to do the Pollock?

PG: Well wait and see. I think it’s exactly the device I intend. Just very briefly and I’m sure we all have some knowledge I think of this painting. There’s an incredible musical play of hands and feet and gestures here, which some people have interpreted and actually musically mutated as a symphonic form which works both backwards and forwards. We’ll examine that with light and with music. There’s almost a cosmography of all the objects on this plate which really does represent and preclude even our contemporary ideas, they say, about the notions of astronomy. Pluto was certainly not known at the time but it is said that Pluto in fact is envisaged about the particular combination of objects on this table. We will write that out large and project it on the ceiling of the refectory so you can understand these connections. The notion of the disposition according to all sorts of Cabbalistic notions based upon initial letters is also very, very significant as we wander through. The martyrs and the non-martyrs are all worked out in a particular order. The geometrical, arithmetical proportions again are all related to Platonic geometry and Euclid and Archimedes and are continued throughout the rest of the actual physical space. In these refectories there was also a way in which one end of the room was always devoted to the last supper and the other to the crucifixion. And the crucifixion actually in this refectory in Milan is by no means a superb painting, though a very interesting one, and there are relationships in a sense architecturally from like a sense of conversation between this painting and the painting on the other side. And the notion, very obviously, of the light – the light of the world – being behind Christ’s head which develops with these panels forever getting bigger and bigger. And so on and so on and so on: a great sense of multilayer hypertexts which da Vinci of course has very, very powerfully instigated into this painting.

Which also means its sense of decay and its sense of ephemerality is also somehow nicely self reflective too. As thought it’s something you really have to look at now because tomorrow it might not be there. So we want to build in that sense not only of the painting being painted but of the history of that painting ever since it has been painted.

MF: Well it’s been a fascinating conversation. We have to go to lunch quite soon but I’m sure we’ve got a few minutes to take some questions. Does anyone have a question for Peter or Franco?

AUDIENCE: I’m Rob Booth from the Guardian. I was just interested in that you talked about you’d had a lot of criticism from certain sectors about what you’re planning to do. Could you explain – and you said you were excited about that as well - so could you explain who’s criticised you, what they’ve said?

PG: Well mainly the Germans and you know how Germans talk about art but don’t make it. There are more manifestos in Germany than there are paintings.

But it’s that notion of ‘as is leave as is’, that notion of a particular perfected time of history, which of course is absolute nonsense and the notion that you are not supposed to give a static image a sense of temporality. You are not supposed to turn a static image into a theatre proposal. You are not supposed to investigate it even in a sense by simply projecting artificial light on it. But we all know all our museums are full of artefacts which have been taken out of context so what context are you taking them from and what context are you outing them back into? So as Franco suggested we will allow the so called public to look at the so called painting in the so called real light. But there’s no such thing as a real light. So this is a very fluid, highly subjective situation. So I think what most of the critics are basically saying is ‘leave alone. The stats quo is good enough’ and you know and I know that’s completely unsatisfactory. And we want to be able to tackle those rather mismatched, ways of thinking and which we look at important works of art.

RB: Sorry, you just said the Germans, but can you be a bit more specific?

PG: It does seem to be a blanket absolute accusation but it is curious, it is. I was fascinated by this. I live just opposite the Rijksmuseum. I have a ticket in my pocket which I can visit this thing, the Rembrandt, virtually any time I like. I’ll tell you an amusing story: you know these artefacts obviously have to be looked after and when we first worked on this painting (we had to work on it at night of course) there were five guards and the jangling of keys. By the time we’d been there about I suppose ten days there was only one guard and after the third week of working they gave us the key to get into the museum. So there’s a sense of trust of course and we’re very happy about that. I hear terrifying things about the British Museum Did you know that they always turn the electrical switches off every night because the British Museum is so full of cats that the guards are up every five minutes running around the galleries to see who’s broken in but it’s only the cats apparently. We’re not supposed to know that of course.

MF: Don’t worry, they can keep a secret.

PG: The knowledge that our National heritage is being safely kept, we can be a bit sort of dubious about that I think.

So, but I think the criticism really is from that famous old phrase notions of the shock of the new, leave it as it is, don’t interfere, don’t change my opinion about it in order to promote your own particular theories. This is a temporary situation. It’s on for two months. We will go away and somebody else can do what they need to do. But I think the general purposes of our intention I hope we’ve explained is simply to get people to look. To examine this extraordinary heritage we all have which even more in an information age is now part and parcel of our total experience.

I proselytise the notion of visual literacy. This is another way to do it.

FL: If I could just add very quickly, there’s been a lot of discussions regarding the way of restoring this painting. What you see… I would say that, I mean maybe you hear this and you believe this is blasphemy but only thirty… you see not a lot, but only I believe twenty percent or thirty percent of what you see is Leonardo. Nearly seventy percent is the work of a restorer. A very great restorer, the name is Pinin Brambilla, but it’s the work of a restorer. So the chance we have also with the new technology is to make a restoration through projection of light; a restoration without restoring. So in a different sense the high technology gives the chance to do something incredible in the direction of restoring the work of the piece of art, the work of a masterpiece without touching it at all. So I think that this is a great opportunity.

PG: There was another feeling too, you know, you should not project bright contemporary light on these paintings. Let me give you another anecdote: you’re probably aware that museums have this system of lux. There’re all sorts of set figures. You go in front of an artwork and you measure the receptivity of light projected on an image and if you take a scale of values I suppose let’s take for arguments sake it’s a hundred the amount of light that we were projecting on this painting was probably in the region of about thirty or forty and when we actually investigated what the museum was putting on it (and they were the people who were obviously the guardians) I suppose their light readings were up in the sixties and the seventies. So what we were doing was far, far less worrying in terms of this notion of how to light an artwork than anything we were doing. I also understand you know most people’s cameras now have got this infra red focussing device. That possibly could be far more dangerous than anything we did. So it’s that feeling again about damaging an important work of art which might also be embedded in this criticism that we were confronted with. I won’t say it was major, major criticism every single day but it was certainly part, I suppose, of the whole argument that we as practitioners who encourage the business of visual interpretation need to take on, need to refute, need to have out in the open if only in a sense to give up arguments to explain the total notion of the context and so forth of the paintings.

MF: One more question here at the front

AUDIENCE: Corrine Julius; Radio Four. One of the things that struck me actually in The Night Watch was, although you’re talking about visual literacy, in order to get that visual literacy sonic literacy is much, much more important.

PG: Well you know I’m meant to be a practitioner of visual imagery and cinema and I’ve always believed that a cinematic experience is sixty percent sound and forty percent image. But again it’s part of the notion of a five senses world. And in a sense to make silent paintings, if you think about it, is more of an aberration than to add sound.

CJ: Sound makes the best pictures.

MF: Do we have one final question? Ok, lunch time. Thank you ever so much to Peter Greenaway, Franco Laera, and to Rosario [Messina, president of Cosmit] for making this [press conference] happen and also for making this far more important event in Milan happen in April.

ENDS

--

Press release issued by Cosmit:

--

Peter Greenaway: Leonardo’s Last Supper

On the occasion of Saloni 2008, British artist Peter Greenaway gives new life to the world’s most celebrated masterpiece, merging an extraordinary wealth of languages including visual arts, cinema, poetry, music and some of the most cutting-edge new technologies.

Saloni 2008 will open with the exceptionally innovative and pioneering event conceived by Greenaway, visionary artist and filmmaker who particularly enjoys Italy and its art history: presenting his audience with a surprising new take on Leonardo’s Last Supper, Greenaway will create an inspiring multimedia event taking place in front of what is undoubtedly the world’s most mysterious and influential piece of art.

Leonardo’s masterpiece has survived both the fast natural ageing process caused by experimental painting techniques conceived by the artist and the many attempts to restore its initial aspect, as well as having outlasted bombings during World War II. The Biblical scene will come to new life under the spectator’s eyes thanks to live projections of images and light bouncing on the very painted surface, accompanied by a soundscape of voices, music and noises.

The performance will take place in the Refectory of the Dominican Friary in Santa Maria delle Grazie Church: on the very wall of the refectory, Leonardo portrayed the moment when Christ announces one of the apostle will betray him, causing disruption and dismay among them. The audience will take turns in groups of twenty-five people at a time, because of the fragile conditions of the painting. The event will loop many times during the evening, outside the normal opening hours.

To offer the same experience to a wider audience, thanks to a groundbreaking combination of sophisticated technology and craftsmanship, a perfect copy of the painting will be realized, a “clone” of the same size and scale, featuring the same exact characteristics and surface texture of the original, which will be on show in the Sala delle Cariatidi in Palazzo Reale during the week of Saloni.

The project makes use of the most cutting-edge technologies ever applied to Leonardo’s fresco, thanks to an international team of collaborators coordinated by Change Performing Arts.

A digital photographic image of Leonardo’s masterpiece was realized by Hal9000, featuring a degree of resolution never reached before; moreover, the Central Institute for Restoration in Rome has provided the 3D scanning of the Refectory in Santa Maria delle Grazie Church. Combining the digital information with the expertise of professional restorers, Factum Arte – directed by Adam Lowe – is realizing the “clone” of Leonardo’s painting.

Reiner van Brummelen – director of photography and collaborator in many of Greeenaway’s cinematic projects – has worked with the British filmmaker on the design of the event, supported by Stereomatrix and V-Factory – Change Performing Arts’ digital media department – and especially by Euphon/Mediacontech Group, Italian leader in digital technologies applied to the media and communications industry.

The event is produced by Change Performing Arts with the artistic direction of Franco Laera. Previous credits of Change Performing Arts commissioned by Saloni include the installation Rooms and Secrets at the Rotonda della Besana, in 2001, and the exhibition 1951-2001 Made in Italy? at the Triennale di Milano in 2001, Imaging Prometheus at Palazzo della Ragione in 2003 and Theatre of Italian creativity in 2003, in New York.

Refettorio del Convento di Santa Maria delle Grazie (16 aprile – 29 giugno 2008)

Sala delle Cariatidi a Palazzo Reale di Milano (16 – 21 aprile 2008)

Credits

Refectory of the Friary of Santa Maria delle Grazie (16 April – 29 June 2008)

Sala delle Cariatidi of Palazzo Reale of Milan (16 – 21 April 2008)

Credits

Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities

Superintendency for Architectural and Natural Heritage of Milan

A project by

Change Performing Arts and Superintendency for Architectural and Natural Heritage of Milan

in collaboration with Municipality of Milan / Culture Council

supported by Central Restoration Institute, Superintendency for Historical and Etno- -anthropological Heritage of Milan, Stereomatrix, Factum Arte, Hal9000, Euphon/Mediacontech Group, V- -Factory

visual design and direction of photography: Reiner Van Brummelen corporate identity: Studio Cerri & Associati

artistic direction: Franco Laera