3D-printed buildings to become reality "in the not-too-distant future"

Interview: 3D printing will revolutionise the way buildings are designed and built - and could herald a new aesthetic, according to Bart Van der Schueren, vice president of Belgian additive manufacturing company Materialise.

"I do believe that in the not-too-distant future we will be able to print really large-scale architectural objects," Van der Schueren said. "We will really see it on a level of houses and so on."

Van der Schueren spoke to Dezeen earlier this year when we visited leading 3D-printing company Materialise in Belgium as part of our Print Shift project, which documented cutting-edge developments in the 3D-printing world.

In this previously unpublished extract from the interview, Van der Schueren predicted that 3D printing would first be used to manufacture cladding for buildings, before being used to print structures containing integrated services such as plumbing and electrical conduits.

"You could think of making plastic structural components, which are covered by metals for aesthetic reasons, or [print] insulation [inside] the structure," he said. "It’s certainly something that I can see developing in the next 5-10 years."

This will give architects radical new aesthetic freedom, he predicted. "I see certainly in the coming years a development where architects will be able to become more freeform in their design and thinking thanks to the existence of 3D printing."

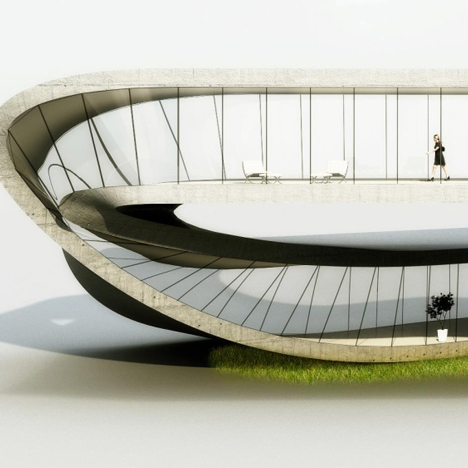

At the start of this year several architects announced plans to build the first 3D-printed house. In January, Dutch firm Universe Architecture unveiled designs for a dwelling resembling a Möbius strip.

Shortly after, London studio Softkill published a proposal for a home made of interlocking fibrous plastic modules (main image). The DUS Architects from Amsterdam announced that they were constructing a canal house in the city, using an on-site printer.

However, none of these proposals have yet been realised.

See our movie in which Van der Scheuren explains the three most common 3D-printing processes. Read more about 3D printing in our print-on-demand magazine, Print Shift.

Here's an edited transcript of the interview with Van der Scheuren:

Marcus Fairs: Is 3D printing of architecture a realistic possibility?

Bart Van der Schueren: There is a potential for 3D printing of architecture. If we are honest with ourselves, 3D printing started in architecture. It started in Egypt, stacking [stone blocks] on top of each other, layer by layer, and that way they created the pyramids. But of course what we mean by 3D printing is slightly different from what the Egyptians did.

What I am seeing happening is that there is a lot of research going on in the development of concrete printers; large gantry systems that extrudes concretes in a layer by layer basis [such as Enrico Dini’s D-Shape printer]. I do believe that in the not-too-distant future we will be able to print really large-scale architectural objects. We will really see it on a level of houses and so on.

But it’s not necessary in architecture to use those large printers. You can see it [working] also on a slightly smaller scale, like the panels that are required to cover architectural structures. Today in lots of cases those panels are limited in complexity because of the fabrication problems. These architectural elements can take advantage of 3D printing’s freedom of design complexity. So here I see certainly in the coming years a development where architects will be able to become more freeform in their design and thinking thanks to the existence of 3D printing.

Marcus Fairs: So it could affect the way buildings look?

Bart Van der Schueren: Yes. It could also affect other things like the integration of facilities into components, like the integration of air channels and cable guides and insulation in one single piece. Or you can think of the integration of loudspeakers in furniture and things like that, so they’re interior architecture. I’m expecting that there will be a big change and shift in the way that architects are thinking and looking and working, and making products as a result of that.

Marcus Fairs: How could 3D printing change architecture beyond the cladding? Could it be used to print more efficient structures?

Bart Van der Schueren: More organic-looking structures are already being investigated. There is research going on to make use of topological optimisation. This is a kind of computer design by which you define by boundaries of certain conditions and then the computer will organically grow a structure that matches the boundary conditions.

This can result in very organic shapes. It will still take a little bit of time, but for cosmetic uses or smaller components it is already possible today.

Marcus Fairs: What new developments are you expecting to see in the near future?

Bart Van der Schueren: 3D printers today are built typically to print with only one material. There are a couple of exceptions but typically a 3D printer will use a single material. What I am expecting is that printers in the future will combine different materials and in that way you can start thinking of making gradients or graded materials where you can then really change the function of the components. From an architectural point of view this can really have fantastic opportunities.

Marcus Fairs: Can you give some examples of this?

Bart Van der Schueren: An example would be mixing metals and plastics. In that way you could think of making plastic structural components, which are covered by metals for aesthetic reasons, or to [print] insulation [inside] the structure. There is still a lot of research to do but it’s certainly something that I can see developing in the next 5-10 years.