Door handles from Lina Bo Bardi's 1951 house go into production

Door handles created by late Modernist architect Lina Bo Bardi for her home in São Paulo have gone into production 62 years after she designed them.

The horn-shaped lever handles are being manufactured by British design brand Izé, founded by Financial Times architecture correspondent Edwin Heathcote, who has licensed the design from the Lina Bo Bardi Foundation.

"They lent us a pair of the original handles from the house which we then copied and cast, then they gave us the rights to produce them," Heathcote told Dezeen.

Bo Bardi created the handles for the 1951 Casa de Vidro (Glass House), which she designed for herself and her husband in the Morumbi neighbourhood of São Paulo. She always intended for the handles to go into production, Heathcote said.

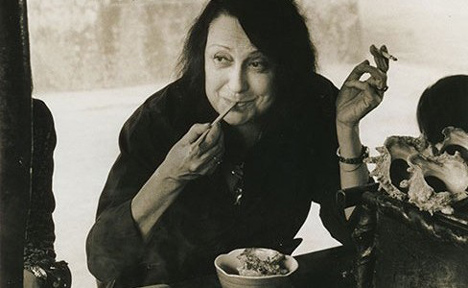

The glass-walled Casa de Vidro, surrounded by jungle and raised up on stilts, has recently been hailed as an important Modernist landmark as part of a wider re-evaluation of the work of Bo Bardi, who was born in Italy in 1914 and died in Brazil in 1992.

"I think it's a particularly humane type of Modernism," said Heathcote, comparing the house to villas by Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe. "I think this building provides a paradigm of how Modern architecture doesn't have to dictate how it's used. It can be looser and more amenable to transformation."

Bo Bardi and her husband Pietro Maria Bardi moved from Italy to Brazil in 1946, where she completed a number of social housing and private projects. Her work, including her São Paulo Museum of Art, has only recently become more widely recognised; last year she was the subject of Lina Bo Bardi: Together, an exhibition at the British Council Gallery in London.

Heathcote believes the delayed recognition of Bo Bardi's work is partly due to Brazil's geographical isolation and partly due to the fact that she is a woman.

"São Paulo is a long way from New York and Europe, where the prevailing trends have been coming from," he said. "It's only now that Brazil is getting richer and opening itself up at lot more. People are travelling there, the arts scene is happening, people in Europe and America are realising how good the architecture in Brazil was."

"I think [it's] probably also because she was a women, much like the Eileen Gray situation," he added, referring to the Irish Modernist designer whose importance was overshadowed by her male contemporaries. "Eileen Gray has only really been picked up in the last twenty to thirty years and has only really been recognised in the last five or six years, and I think its the same with Lina Bo Bardi."

Heathcote set up Izé in 2001 to produce door handles and other fittings for architecture projects. "It turned out that the door handle was, proportionate to its size, was the most influential piece of the building that I could think of that I could get into manufacture," he said. Previous products include handles designed by Studio Toogood and Eric Parry.

Photos of Casa de Vidro are by Edwin Heathcote. Here's an edited transcript of the interview with Heathcote:

Daniel Howarth: How did you come to set up a company making door furniture?

Edwin Heathcote: My background is in architecture and I have always been interested in production and the design of the object. I gave up architecture but I was still interested in the design and being part of the building process, I tried to isolate the smallest but most important element that would lend itself to manufacture; I didn't want to get involved in the whole building process.

It turned out that the door handle was proportionate to its size; it was the most influential piece of the building that I could think of, that I could get into manufacture. We started by reviving some of the designs from the twenties and thirties and then the fifties. We started commissioning people at the same time, and we've been plugging away at it for a dozen years.

Daniel Howarth: How did you get the rights to produce the Bo Bardi handle?

Edwin Heathcote: We worked with the Lina Bo Bardi Foundation, which is based in the house she designed for herself, the Casa de Vidro in São Paulo. Over the period of a about a year they lent us a pair of the original handles from the house which we then copied and cast, then they gave us the rights to produce the handles.

Daniel Howarth: Why is the house and the design so special?

Edwin Heathcote: I think it's a particularly humane type of Modernism. I think that there's been a type of Modernism that's been made iconic, the kind of Corbusian villa has become the kind of symbol of the Modernist house. The Corbusian villa and Mies' Farnsworth House offer these sort of twin poles, and they're very keen to achieve a kind of perfection. I think that the Lina Bo Bardi house is looser, it has a kind of humanity to it that is slightly lacking in both of the other, both in Corb and in Mies.

It has a sort of, I hesitate to say, a Brazilian joie de vivre. But I think its something of that in it, this house in the jungle, the way it's integrated into the landscape is very informal. Inside you have this feeling that you're part of the landscape, the tree comes through the middle of the house and the courtyard. It somehow much more integrated in the surroundings. It's a sort of alternative Modernism.

Daniel Howarth: What makes Bo Bardi stand out as an architect?

Edwin Heathcote: There's one building in particular: SESC Pompéia [a former factory in São Paulo that Bo Bardi and her husband converted into a multi-purpose building between 1977 and 1982]. That building in particular has been up by contemporary commentators as an example of how you can achieve quite a fierce Modernism, using existing industrial buildings and an existing urban context, and create a real piece of city, create a functioning, organic piece of city, which is adaptable and which people can adopt as their own.

I think the tendency of Modernism has been to impose a building which is either then used or not used. Obviously some Modernist social housing is an example of the failures. But I think this building provides a paradigm of how Modern architecture does't have to dictate how it's used. I can be looser and more amenable to transformation.

Daniel Howarth: Why was she unrecognised for so long?

Edwin Heathcote: I think São Paulo is a long way from New York and Europe, where the prevailing trends have been coming from. There's this kind of band of LA, New York, Europe, Japan, which have been the northern hemisphere grouping that has dominated architectural culture. I think it's only now that Brazil is getting richer and opening itself up at lot more, people are travelling there, the arts scene is happening, people in Europe and America are realising how good the architecture in Brazil was, I think for a long time they just hadn't really noticed. They were too concerned with their own issues.

I think [it's] probably also because she was a women, much like the Eileen Gray situation. Eileen Gray has only really been picked up in the last twenty to thirty years and has only really been recognised in the last five or six years, and I think its the same with Lina Bo Bardi.