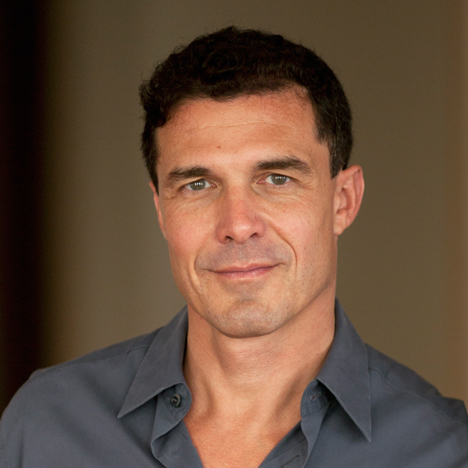

"We don't go to architects who have a signature style" says André Balazs

Interview: hotelier, restauranteur and developer André Balazs is the man behind The Standard in New York, Chateau Marmont in Hollywood and Chiltern Firehouse in London. He told Dezeen why his approach is "kind of like an old-school Hollywood studio" (+ slideshow).

Besides the glamorous hotels and restaurants, Balazs has also developed residential buildings in New York with architects Jean Nouvel, Richard Gluckman and Calvin Tsao.

However, he carefully avoids giving big names free reign on his projects, preferring instead to invite a range of external collaborators to work with his in-house team.

"One of the reasons we have such a big in-house design team is that we don't like to go to architects who have a signature style," he said in a telephone interview with Dezeen from his New York office. "Because then you get their signature style. So frequently we go to younger people who haven't yet developed a signature style."

Balazs hired Nouvel to design 40 Mercer, a New York apartment building, in 2002, before the French architect achieved superstardom by winning the Pritzker Prize. But Nouvel wasn't allowed to do the interiors. "I got Antonio Citterio to do the interiors, because I thought Jean was going to be too tough and hard," Balazs said.

Born in Boston in 1957, Balazs heads André Balazs Properties, which owns and operates the Standard hotel chain. It has five properties across the USA and a new outpost under construction in London, in the Brutalist former Camden Town Hall building on Euston Road.

The building contrasts starkly with Chiltern Firehouse, currently London's most celebrity-saturated hangout, which occupies an opulent Neo-Gothic former fire station in Marylebone.

In fact, none of Balazs' properties bears any resemblance to any other, a result of his approach of treating each new project like a movie script.

"I see my role and my company's role as kind of like an old-school Hollywood studio," he said. "We kind of put together who's the best writer, director, who are the actors we can bring in, who's the best production designer, the best composer and we'll assemble a team. We have people designing uniforms, people designing various aspects of it."

"It's very collaborative, it's a large team effort. You cannot look at any of these places and say this designer did it. They all had very significant contributions."

Balazs is an admirer of mid-century French architect and engineer Jean Prouvé. He owns Prouvé's Maison Tropical, a two-storey steel and aluminium prefab originally erected in Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo in the 1950s.

Earlier this summer this led to Balazs being invited to guest curate Design at Large, an exhibition of mobile, modular architecture held at the Design Miami collectors' fair in Basel. The exhibition included Shigeru Ban's cardboard tea house, Atelier van Lieshout's cave-like fibreglass Original Dwelling and Ikea's refugee shelter, as well as a petrol station designed by Prouvé.

"Given the loose outline of the show – which was prefabrication, modularity, sustainability, a lot of buzz words – and given the highly articulated restaurants and clubs that we've done, that was probably why I was asked to curate it," Balazs said.

"It probably has a lot to with the fact that Jean Prouvé is such a seminal figure in the show. [Prouvé] had originally explored many of these things in his work. [He developed] an architectural and manufacturing methodology and protocol meant to solve very practical needs such as erecting a school quickly or creating affordable housing in a tropical climate."

"Not only was he a genius in terms of aesthetic design but he was also dealing with a lot of these issues. Some unsuccessfully, but he was dealing with them."

Below is an edited transcript from our interview with André Balazs:

Marcus Fairs: How did you get involved in the Design at Large exhibition at Design Miami?

André Balazs: The Design Miami people, [Design Miami director] Rodman Primack in particular, asked me to do it. It probably has a lot to with the fact that Jean Prouvé is such a seminal figure in the show.

Several years ago I bought at auction what I consider to be one of his most interesting houses – the Maison Tropical – which I then showed at Tate Modern about six years ago.

So given the loose outline of the show – which was prefabrication, modularity, sustainability, a lot of buzz words – and given the highly articulated restaurants and clubs that we've done, that was probably why I was asked to curate it.

In my mind I wanted to frame the intellectual concept of the show just to answer the simple question: why this show, why now? I had to keep coming back to Prouvé. He had originally explored many of these things in his work – I mean modularity, sustainability, and things like that.

[He developed] an architectural and manufacturing methodology and protocol meant to solve very practical needs such as erecting a school quickly or creating affordable housing in a tropical climate. Not only was he a genius in terms of aesthetic design but he was also dealing with a lot of these issues. Some unsuccessfully, but he was dealing with them.

Marcus Fairs: How do you go about choosing architects and designers for your projects? Your hotels, restaurants are all very different from each other.

André Balazs: They're extremely different. We've also along the way done three ground-up residential developments in New York City, ranging from a relatively small one on the edge of SoHo [One Kenmare Square], which we did with Richard Gluckman to a super-luxury building in a historic district in SoHo with Jean Nouvel. It was before he won the Pritzker Prize, it was his first building in the United States.

The only person in the world who I thought was appropriate for working in that kind of muscular architecture, namely the cast iron for which SoHo is known and protected, was Jean Nouvel. So we started working with him [on 40 Mercer]. It was meant to be a hotel, until 9/11, when we had to switch it to residential. And I got Antonio Citterio to do the interiors, because I thought Jean was going to be too tough and hard.

And we did [William Beaver House], a 330-unit, 48-storey tower with Calvin Tsao [of Tsao & McKown], which is in the financial district, in Wall Street.

So I think whether it's architecture, interior design or decorating – which is distinct from interior design, which is more programatically focused – I really start off by imagining a story for the building and then together with our internal design team, which is very oriented towards the production, we bring in different people who might help address that particular narrative.

In the case of let's say the Standard High Line in Manhattan, it was being built on an empty lot and I didn't want to do a replica of a building that would have been a cast-iron framed building. I thought that would be Disneyesque and meaningless.

And then with the Standard High Line we worked with James Stewart Polshek, who was the dean of Columbia's Graduate School of Architecture at the time, because it was going to be something very, very classically New York. It was not a historic district. We could build entirely as we wanted. And Todd Schliemann, who at the time was a partner in the firm that is now ENNEAD, Todd is someone I've known for a long time, we went to school together at Cornell Architecture School. Here we wanted to build a building that was an expression of the brand, the Standard brand.

That was a ground-up construction. So we brought in a guy called Shawn Hausman, who was a set designer but has worked for various Standards, and paired him with Roman and Williams to do the production work, and worked with all of them in house. And in each case the team that was put together was put together because there was some sort of vision of what was needed.

Chiltern Firehouse for example: many years earlier I had seen a project in Morocco, a small hotel, that I had admired. I looked at Olivier Marty, who's one of the partners at Studio KO, I worked with them along with architect David Archer, who had worked in my office for years.

It's a Grade 1 listed building. David worked on the architecture, Studio KO was brought in for some of the interiors. So there's a story for each of them. We put a team together to illustrate a narrative.

Marcus Fairs: How do you see your role in these projects?

André Balazs: I see my role and my company's role, in addition to operating hotels and restaurants, as kind of like an old school Hollywood studio. We will say, look, we're going to make a surfing movie.

Marcus Fairs: A surfing movie?

André Balazs: Let's say I was a studio head and I said I think the market is right to do a movie based on surfing. Or let's do an adventure thriller. We kind of put together who's the best writer, director, who are the actors we can bring in, who's the best production designer, the best composer and we'll assemble a team. We have people designing uniforms, people designing various aspects of it. It's very collaborative, it's a large team effort. You cannot look at any of these places and say this designer did it. They all had very significant contributions.

Marcus Fairs: So you're not after a signature building?

André Balazs: You know one of the reasons we have such a big in-house design team is that we don't like to go to architects who have a signature style. Because then you get their signature style. So frequently we go to younger people who haven't yet developed a signature style.

Even Christian Liaigre, when we did The Mercer, was not the Christian Liaigre who became well known for a particular look today. In fact the look he's known for today is a direct consequence of where we collaboratively got to in the process of doing The Mercer.

So the reason we have an in-house team is that most people we work with have never done what we're asking them to do. So much of the production, filling in the gaps, comes from our more seasoned in-house team, but the flavour and the direction is why we team up with whoever I think is the right designer or architect. The projects don't really require architecture. Some do, some do only for a period, and then they need different levels of planning. Much of the interior design in the sense of planning – in fact all of it – comes from us. And then we team up with a decorator or an architect.

Marcus Fairs: What's the movie script for the Standard in London?

André Balazs: We just began interior demolition at the Camden Town Hall building. Camden's history, there's a certain political history to Camden that's relevant in the thought process. It's very relevant that it's a building of a certain sort of Brutalist architectural nature, from the early 1970s. This all becomes part of the narrative that we deal with. It is Kings Cross, it is across from St Pancras, it's Camden, it's a Brutalist building. So those are the starting points to weave some kind of story.