"Appreciating the role of colour in architecture is a great missed opportunity of the Bauhaus"

It's a shame that, although colour theory was taught at the Bauhaus, it wasn’t significantly applied to architecture, says Michelle Ogundehin in this Opinion as part of our Bauhaus 100 series.

The Bauhaus employed four artists whose theories on the use of colour underpin everything we think of as contemporary colour theory. So why, despite this enduring influence, did they have so little impact on the architectural output of the day?

At its simplest, theorising about colour can be broken down into three core lines of enquiry: how should colours be ordered, which ones work best together, and how might they most "correctly" be employed.

And while Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus, was renowned for his personal disdain for the use of colour in his buildings, it's testament to his desire for debate that colour theory was taught as part of a mandatory foundation unit at the school. However, it's notable that he invited artists to do this, not architects.

As such, the course was led initially by the Swiss expressionist Johannes Itten, followed by Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and finally Josef Albers; each adding their own unique twist to the quest to decipher colour.

It's testament to Gropius' desire for debate that colour theory was taught as part of a mandatory foundation unit

Originally trained as a primary school teacher, Itten, driven by a desire to impose a logical structure upon the spectrum, had a very methodical way of working. Although he wasn't the first to come up with a colour wheel – that honour is said to fall to Sir Isaac Newton in 1666, and certainly many after Newton did the same – the sophistication of his approach distinguishes him, and ensures many of his ideas remain relevant today.

For although he arranged colour in the traditional format of primary, secondary and tertiary colours, he further refined his wheel with theories of seven possible modes of contrast between the shades. As he put it, "he who wants to become a master of colour must see, feel, and experience each individual colour in its many endless combinations with all other colours. Colours must have a mystical capacity for spiritual expression, without being tied to objects."

Thus, notwithstanding his rigorously analytical thinking, he also highlighted the less tangible, psychological affects of colour and was one of the first to associate different hues with varied personality types, as well as the idea of warm versus cool colours. In this way, much current seasonal colour analysis, particularly as used by the cosmetics industry, owes a debt to the teacher turned painter.

Post Itten, Kandinsky, a Russian pioneer of abstract modern art, taught at the school until it closed in 1933. He encouraged his students along a more freewheeling and emotive path. For him, colour had profoundly spiritual connotations and he believed it could only be interpreted as a kind of musical score with certain colours expressed as specific notes (for example yellow was a middle C).

And yet, in a move that I find contradictory to his musical analogies, he also assigned to colours geometric shapes; thus yellow was also best represented as a triangle; blue by a circle, and red always as a square.

But the direct application of Kandinsky's theorising to architecture was negligible

Regardless, the very confluence of these seemingly opposing paradigms resulted in the paintings which made him famous, and arguably inspired many great artists that followed from Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock to Julian Schnabel. But the direct application of Kandinsky's theorising to architecture, or even design, was somewhat more negligible.

His teaching at the Bauhaus overlapped with that of the Swiss painter and printmaker Paul Klee, very much a comrade in arms. He supported Kandinsky's ideas of colour harmony and its relation to music, and also passionately advocated its disassociation from a purely naturalistic, representative role in art. For both Klee and Kandinsky, the sensorial potential of colour was its true power, whether neatly categorised or not.

Disappointingly though, it seemed it was only within the privacy of their own homes that either felt able to take their colour concepts off the canvas and into their surroundings. The pair lived in adjacent semi-detached houses for six years, and when renovation work was carried out on the properties in the early 1990s, reports revealed some seven-different layers of paint and over 200 shades applied to the walls.

For both Klee and Kandinsky the sensorial potential of colour was its true power

Built by Gropius as part of the Dessau campus, the exteriors were all classic white and grey intellectually-inspired modernism, but inside had become a kaleidoscopic riot. Kandinsky's living room is documented as having been yellow, pink and gold leaf; the bedroom cyan and the entrance boasting pale violet walls, a black floor, and a staircase in yellow and white with a bright red handrail.

Next door, Klee contrasted red lacquer with plaster pink, baby blue and grey. How exciting it might have been if this experimentation had been more openly discussed and carried forth into the architecture and interiors of the Bauhaus movement itself, rather than being closeted away as personal play.

A degree of salvation then was seen in the appointment of Josef Albers. The son of a painter and decorator he was a working class, church school-educated misfit among the wealth and privilege of the other masters, but it was he who got closest to solving the colour classification conundrum; in that he rejected it.

In his book, Interaction of Colour, published in 1963, he wrote: "In visual perception a colour is almost never seen as it really is – as it physically is. This fact makes colour the most relative medium in art. In order to use colour effectively it is necessary to recognise that colour deceives continually. To this end, the beginning is not a study of colour systems."

When one thinks of the Bauhaus it is probably only strictly monochromatic visions of its iconic architectural output that come to mind

In place of such systems then he proposed a more inclusive way of working that revolved around context and crucially, he understood that his pursuit was not for a single "solution" but rather a continual, and highly subjective, journey of discovery.

Unfortunately for the students of the Bauhaus, the opportunity to develop his ideas only came once he'd left the school, first at the Black Mountain College in North Carolina where he and wife Anni fled after the Nazis gained control in Germany, and then at Yale, from where he eventually published his seminal tome.

And so it is that when one thinks of the Bauhaus, if not the modern movement as a whole, it is probably only strictly monochromatic visions of its iconic architectural output that come to mind. Certainly there is no doubt that it was a powerful catalyst for stylistic change; however it was driven by an almost exclusively well-to-do male cabal and that came with limitations.

In short, appreciating the role of colour in architecture is one of the great missed opportunities of the Bauhaus. While the school appeared open to discussion about colour, the overriding sentiment was to contain and classify it, then move on, with the implication that colour was incidental, rather than fundamental, to the built environment.

In other words, good for art and theory, but dare I say it, potentially too feminine for the might of architecture. Then again, even Itten acknowledged, "only those who love colour are admitted to its beauty and presence. It affords utility to all, but unveils its deeper mysteries only to its devotees."

Pause for thought then on how much richer Gropius's Bauhaus legacy might have been if he'd allowed his artists to truly impact his practice. After all, it's only when theory is translated into active truth, that ideals really come to life.

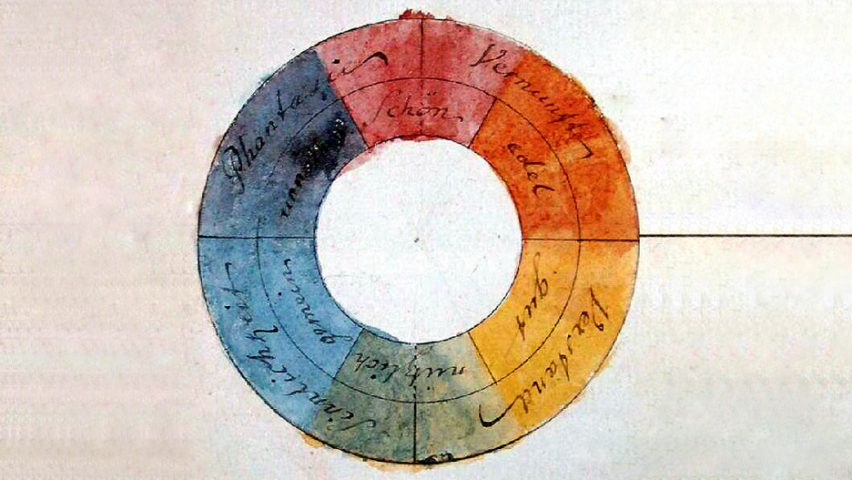

Main image shows Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's colour wheel from 1810.