Anni and Josef Albers: the married misfits of the Bauhaus

Anni and Josef Albers met at the Bauhaus and both became hugely influential designers. As we continue our Bauhaus 100 series celebrating the school's centenary, we explore the couple's works and legacy.

The Bauhaus had its fair share of couples, not to mention love triangles. But the most enduring was no doubt Anni and Josef Albers, she a middle-class Berliner of Jewish descent, and he the son of a painter-decorator from the town of Bottrop, Westphalia.

Anni, born Annelise Fleischman, hailed from upmarket Charlottenburg. Her mother's family included the founders of the Ullstein publishing empire and her father was the owner of Trunck & Co, a successful furniture business. Early attempts to study painting met an abrupt end when Austrian artist Oskar Kokoschka, upon seeing her works, simply asked "why do you paint?"

As the story for many Bauhausians goes, Anni chanced upon a manifesto while studying at Hamburg's School of Applied Arts, and aged 23 headed to Weimar to apply.

Anni and Josef met at the Bauhaus

On her arrival in 1922, Anni would meet Josef: 11 years her senior and at that point recently appointed junior master. Anni's plans at the Bauhaus went the way of many female students, pushed away from skills such as woodwork, sculpture and painting, which Walter Gropius termed "heavier crafts", and towards its most "feminine" discipline: weaving.

As a man, Josef was better respected, but his working-class background made him something of an outlier compared to the predominantly middle-class school: together, the two have been referred to as the misfits of the Bauhaus.

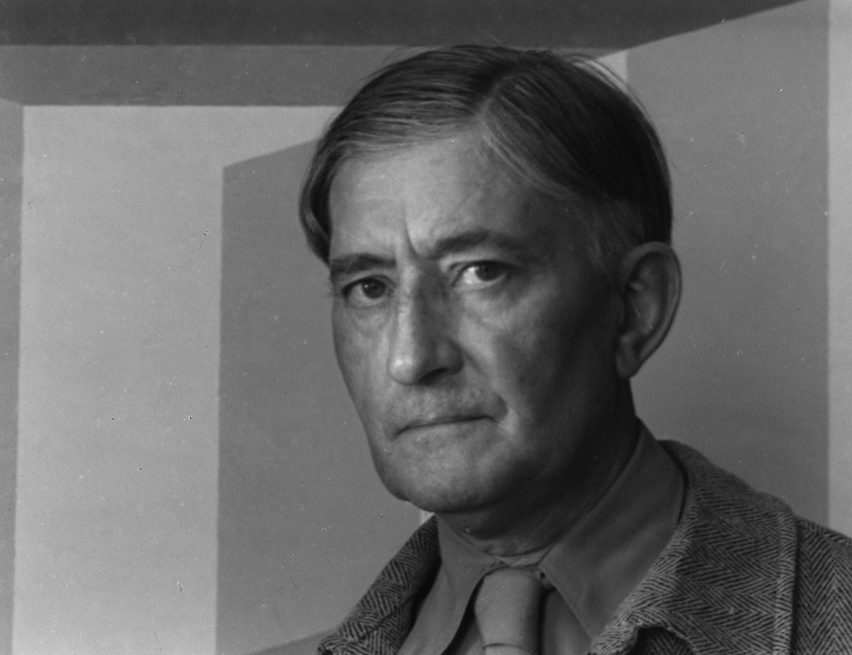

Josef had joined the Bauhaus in 1920, at the age of 32. He had already worked as a teacher in his hometown of Bottrop, and at the Royal School of Art in Berlin, and studied printmaking at the School of Arts and Crafts in Essen. He was also already exploring the glasswork for which he would become famous, receiving his first commission in 1918 for a stained-glass window at a church in Essen.

The Albers were initially frustrated at the Bauhaus

With more experience than the average student, there was a sense that Josef knew very much what he wanted to get out of the Bauhaus, but the school had other ideas.

Enrolling first on Johannes Itten's preliminary course, Josef was then begrudgingly steered towards Kandinsky's wall painting workshop, a time of which he has said: "I had learnt wall painting in my father's workshop. I went to the wall painting workshop only to help my friends".

Josef's passion, glass painting, was considered a "branch" of wall painting, but Albers took this into his own hands, skipping classes to rummage for glass in the town dump and create his early "shard paintings" such as Gitterbild, a stained-glass like grid of metal scraps connected by bent wire.

Seeing these at a student show, Gropius was taken with them enough to appoint Josef as a junior master before he had even completed his apprenticeship exams, becoming head of the glass workshop.

Anni's early years at the school shared a similar sense of frustration: "fate put into my hands limp threads!", she said of attending the weaving workshop – like Josef, she would've preferred glass. But while Josef responded by staging his small rebellion, Anni set about experimenting, turning this traditional medium into shockingly modern works.

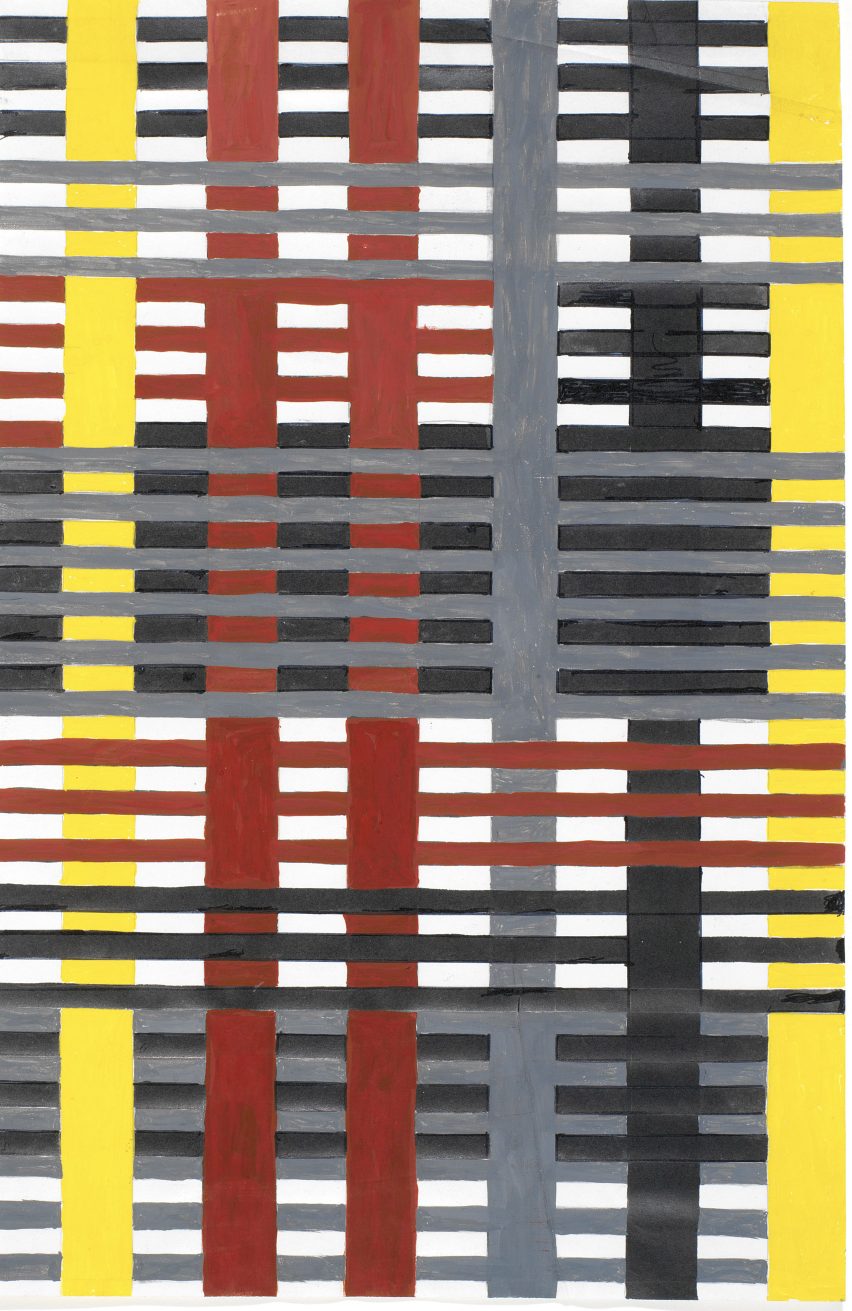

"Gradually", she recalled, "threads caught my imagination". Soon both Josef and Anni were turning paint, glass and thread to vivid explorations of geometry, colour and grids – and soon they were married, in 1925.

Both students became masters

The pair honeymooned in Florence, while the Bauhaus was facing turmoil in Weimar, and soon after their return Josef was appointed master at the new school in Dessau – making him the first Bauhaus student turned Bauhaus master.

Anni designed wall-hangings for the quarters in Gropius' new building (and they would later collaborate on more works, such as the Harvard Graduate Centre), but the shift from craft towards functionalism at the school saw her work turn towards more practical concerns.

It was a soundproof and light-reflecting wall covering made from cotton, chenille and cellophane that would earn Anni her diploma. Briefly, she was a student of Paul Klee, echoing his idea of "taking a line for a walk" with her own desire "to take thread everywhere", and in 1931, with the departure of Gunta Stölzl, Anni took over as head of the weaving workshop.

The Albers moved to the United States at the invitation of Philip Johnson

Following the school's closure, the Albers moved relatively quickly to the United States, arriving in 1933 following an invitation from Philip Johnson to teach at the Black Mountain College – Johnson referred to Anni's diploma wall covering as the pair's "passport to America".

This experimental school, founded in the same year by John Andrew Rice, was based around the principles of educational reformer John Dewey, and in its 24 years of operation was home to many hugely influential figures, including Gropius.

Rice recalled how the Bauhaus "had evidently not been paradise" for the Albers, caught up as they were in its thoroughly un-modern institutional views on class and gender, but Anni would later praise the school's "unprejudiced attitude towards materials and their inherent capacities".

Her architectural collaborations continued, working with Johnson on the Rockerfeller Guest House, but at the newly established Black Mountain weaving workshop, Anni explored "pictorial weavings", works intended as art to be displayed rather than for everyday use.

The Albers were prolific artists until their deaths

In 1950, the Albers moved to New Haven, Connecticut, with Josef appointed head of design at Yale University. Around this time, he was producing what would become some of his most famous abstract paintings in the Homage to the Square series, and in 1963 he published Interaction of Colour, based on his theories of an internal logic governing colour – since made into a phone app. These were accompanied by a series of high-profile glass and painted murals.

A few years later in 1965, Anni would publish her famous text On Weaving, having a powerful impact on textile arts in the United States.

Both continued to be prolific artists, educators and authors until their deaths, Josef in 1973 aged 88, and Anni in 1994 aged 94. The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in Connecticut, founded five years before Josef's death, continues to look after the Albers's estate and support exhibitions and publications: their impact on their respective art forms, as well as modern art education in America, is undeniable.

The first major exhibition of Anni Albers' work in the UK is taking place at the Tate Modern from 11 October 2018 to 27 January 2019.

The Bauhaus is the most influential art and design school in history. To mark the centenary of the school's founding, we've created a series of articles exploring the school's key figures and projects.

See the full Bauhaus 100 series ›

Main illustration is by Vesa Sammalisto, additional illustration is by Jack Bedford.