Deconstructivism "killed off postmodernism" says Peter Eisenman

The legacy of deconstructivism was the death of postmodernism, says US architect Peter Eisenman in this exclusive interview as part of our series investigating the 20th-century style.

One of the best-known architects of the 20th century, Eisenman is widely considered to be part of the deconstructivist movement. However, he dislikes the term.

"I'm very much against deconstructivism," Eisenman told Dezeen. "I think it's a sham. I mean, it doesn't exist."

"That's why I'm surprised that you guys who represent architectural thinking are running a series on something that is absolutely false," he continued.

The term deconstructivism – a combination of the deconstructionist approach to philosophy and the constructivist architecture style – was popularised by a show at the MoMA museum in New York in 1988.

"The show at MoMA was a made-up idea of deconstructivism by [co-curator] Mark Wigley, who actually knew better," added Eisenman.

Eisenman was a follower of ideals of deconstruction that were developed by philosopher Jacques Derrida and considers himself a deconstructionist architect rather than a deconstructivist one. He explained that of the others in the exhibition, only Bernard Tschumi "had any interest in deconstruction".

He didn't, and still doesn't, see the connection with constructivism – a style of architecture that was developed in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s.

"There is nothing in constructivism that has anything to do with breaking down hierarchy, breaking down relationships, one to one related sign and symbol," he said.

"So if you want to talk about deconstructivism we can, but I want the caveat to be that it's a bunch of junk."

Although he didn't approve of the term, Eisenman took part in MoMA's seminal exhibition alongside architects Tschumi, Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, Daniel Libeskind and Coop Himmelb(l)au.

He agreed to participate partly to make up for declining an invitation to be part of the Strada Novissima exhibition at the inaugural Venice Architecture Biennale in 1980, which was hugely influential and included many of the best-known architects of the era.

"I didn't go in to [Strada Novissima] and that was a dumb mistake," explained Eisenman. "It was stupid to stay out. Everyone went in. Aldo Rossi went in, Massimo Scolari, all of Tafuri's team went in. So that was in 80."

"So in 88 when this chance to go into MoMA happened, I said 'screw that. I'm not going to miss the second one'," he continued. "So that's why, clearly, I went in. But knowing that I didn't like deconstructivism as a thing."

He believes that the draw of exhibiting at MoMA was the reason that the other architects agreed to be part of a show that "made the careers of Frank Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid".

"First of all, they were caught," he explained. "They didn't want to be part of a group and I understood that. They didn't want to be part of this group for sure."

"The fact that MoMA gave over a giant space, for monkeys to go and showed their toys, you don't see that anymore. To get into MoMA, or any museum of sensibility. You don't have seven crazy architects. That was a crazy moment."

The architects featured in the MoMA exhibition all shared a way of form-making that rejected the ideals of postmodernism, said Eisenman.

"I think you could say, the iconic forms [are shared]," he said.

"In other words, if modernism was a white box, and Pomo was a grey box with decoration – with whipped cream on it, sprayed out of a can, deconstructivism broke the box open, and you had basically shards," he continued.

"It was a different way of making that didn't start from the box. It started from those shards or fragments. And all of us had that in general, Tschumi, myself included, I would say less than some of the others. But basically, we were shard makers.

Eisenman acknowledges that deconstructivism had a huge impact on the trajectory of 20th-century architecture.

"It killed off postmodernism," he said. "Kitsch postmodernism was at the high point at the Venice Biennale in 80 and deconstructivism killed that off."

"It killed off the decorated shed, that I'll take," he continued. "That's a legacy. I never had thought about it before now, but I would say, that's actually what happened."

Read on for an edited transcript of the interview with Eisenman:

Tom Ravenscroft: Can you tell me how you define deconstructivism?

Peter Eisenman: I'm very much against deconstructivism. I think deconstructivism is a sham. I mean, it doesn't exist. That's why I'm surprised that you guys, who represent architectural thinking, are running a series on something that is absolutely false.

Number one, deconstruction is not deconstructivist, okay? Deconstruction is a serious philosophical idea. It contains two basic ideas that interest me as an architect. One, it attempts to break up the hierarchies that exist in any common English speak – like up/down, in/out, black/white, etc. Dualities and dialectics are always based on hierarchy.

Number two, it was about the free play of signifiers. That was what Derrida was about. And he was very much against what he called the metaphysics of presence.

The show at MoMA was a made-up idea of deconstructivism by Mark Wigley, who actually should know better because I reviewed his PhD thesis. I was his external examiner and he did a brilliant job on deconstruction. Mark Wigley knows absolutely well, that deconstruction and deconstructivism are two different things.

In any case, I thought the show did two things unexpectedly, it killed off postmodernism, finally in 1988. Kitsch postmodernism was at the high point at the Venice Biennale in 80 and deconstructivism killed that off, but it also killed off itself at the same time. It had no purchase after a couple of years.

But it made the careers of Frank Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid – those people all went on to be hero figures in architecture. And I think the only one who really had any interest in deconstruction was Bernard Tschumi. Who was almost left out of the exhibition, but that's another story...

So if we are talking about deconstructivism, I'm the wrong guy.

Tom Ravenscroft: So why did you contribute to the 1988 MoMA exhibition?

Peter Eisenman: Well, in 1980 I was asked by Paolo Portoghes to go into the Strada Novissimam, which was the ultimate of the Pomo kitsch sensibility. But Manfredo Tafuri, with whom I was friendly at the time, called me and said Peter you cannot go into that show as it's against what you and I believe in.

I didn't go and that was a dumb mistake. It was stupid to stay out. Everyone went in. Aldo Rossi went it, Massimo Scolari, all of Tafuri's team went in. So that was in 1980.

So in 88 when this chance to go into MoMA came up, I said "screw that, I'm not going to miss the second one". So that's why I went in. But, knowing that I didn't like deconstructivism as a thing.

There is nothing in constructivism that has anything to do with breaking down hierarchy, breaking down relationships, one to one related sign and symbol. So if you want to talk about deconstructivism we can, but I want the caveat to be that it's a bunch of junk.

Tom Ravenscroft: It sounds like you don't have an issue with the deconstruction part of the term, but do have an issue with the constructivist part of the term?

Peter Eisenman: Quite true. Constructivism has nothing to do originally with deconstruction as a philosophic idea. And the only people that would understand that are Bernard, Mark Wigley and myself. The rest of the guys didn't like it, but they wouldn't know why. And they didn't mind the publicity.

Tom Ravenscroft: So what traits do you think you and the other six in the MoMA exhibition shared?

Peter Eisenman: You could say the iconic forms. In other words, if modernism was a white box, and Pomo was a grey box with decoration – with whipped cream on it sprayed out of a can – that deconstructivism broke the box open. You had basically shards.

You wouldn't have a pickle building today in London if it hadn't been for the decon show, because the idea that the figure was the ground was a new idea. And the minute you don't have a frame for the figure, that figure can become the ground.

And so that was what these guys and myself included had in common. Certainly Wolf Prix's thing on the rooftop in Vienna, certainly Zaha's The Peak, Frank Gehry always, and still. But, those things have nothing to do with Russian constructivism. Rem is the only legitimate heir to Russian constructivism. He was doing models of Russian stuff when I first knew him in New York in 73 or 74.

Tom Ravenscroft: So what you shared was a new way of form-making?

Peter Eisenman: Yes, a different way of making that didn't start from the box. It started from those shards or fragments. And all of us had that in general, Tschumi, myself included, I would say less than some of the others. But basically, we were shard makers.

Tom Ravenscroft: Where do you think the shared desire to rethink form-making came from?

Peter Eisenman: We came after four iconic architects, Rossi, [Robert] Venturi, [Oswald] Ungers and [James] Sterling. My generation doesn't have that. As a generation, those guys really did some really interesting things.

My generation, that is those in that show, never quite believed in those guys as a didactic, intellectual or conceptual force. And you can see it in Rem's work and Wolf's. In mine as well. Danny, I mean, we were all different, but not quite as iconic as Jim and Ungers.

Deconstruction was only one way of explaining this, as far as I was concerned. There were, I mean, Frank's stuff is new expressionism, Rem's stuff is new cool.

I think that those seven architects were pretty much what came after the postmodern four, let's say. Oh, I would put [Alison and Peter] Smithson in for five.

There's been nothing since then, I mean, architecture schools have no pedagogy. There's no social presence, there's no idea of what to teach, what to build.

The reason, I think, is because the client has become a developer. Where the developer is, is not about where architecture could be. We don't have meaningful people now. I mean, there are some young people – there's a group in London. What are they called? Assemble. They're really good. They're they're meaningful. They're serious. So I think they're one of the best young groups.

Tom Ravenscroft: Were there shared values for the deconstructionists – maybe Derrida, Bernard and yourselves?

Peter Eisenman: That's it. The rest? First of all, they were caught. They didn't want to be part of a group and I understood that. They didn't really want to be part of this group for sure.

The fact that MoMA gave over a giant space, for monkeys to go and show their toys, you don't see that anymore. To get into MoMA, or any museum of sensibility. You don't have seven crazy architects. That was a crazy moment.

Tom Ravenscroft: So do you think the exhibition popularised the term? And that you seven couldn't say no to the press, including yourself by the sounds of it?

Peter Eisenman: I've always said that. Mark wrote a terrific book on deconstruction. Why we had to have deconstructivism, you really should talk to Mark about it. Did you speak to Bernard?

Tom Ravenscroft: Yes. And Daniel, Frank said he wasn't a deconstructivist.

Peter Eisenman: In Joseph Bernini's book, it says that Frank was the only deconstructivist. I love Frank. Frank and I are going to do a semi-final studio for both of us at Yale in the fall. We're going to do a diptych studio, okay. A build sort of Romeo and Juliet, Yogi and Boo Boo. And we're two different people and it's going to be a wildly interesting studio.

Last one. Both of us are over 90. And we are brothers of a strange sort. Let's say. I love Frank. I've always said that. I always have the analogy of two race cars. And my race car was always with the windshield covered in mud being split up by Frank's tires out front.

But you know, he isn't a deconstructivist because there is no such thing as a deconstructivist. Wolf maybe, the Hong Kong project of Zaha's is possibly a decon project. Danny, I don't know what you want to call what Danny does. Bernard, I don't think so. Basically, Wolf and Zaha come closest to whatever that is.

Tom Ravenscroft: And you and Bernard are deconstructionists not deconstructivists?

Peter Eisenman: I think I'm a deconstructionist. Yeah. I mean, I didn't want to talk about deconstructivism because I don't want to say anything bad about it.

I think it finished post-modernism. That's quite something. We didn't realise that was going to happen. But it did.

Michael Graves and I were really friendly. We started out together at Princeton. And Michael turned out to be an arch postmodernist. Most talented, but he was upset and so was Charles [Moore], that they weren't included. I mean, when your friends are in the MoMA, celebrating what the hell else? And you're not included. That's not good.

Tom Ravenscroft: So is killing Pomo the legacy of deconstructivism?

Peter Eisenman: That's great. It killed off the box as well. It killed off the decorative shed. Call it this way. Of all the things that Venturi did one, of the most iconic was the decorated shed. It killed off the decorated shed, that I'll take. That's a legacy. I never thought about it before now, but I would say, that's actually what happened.

Tom Ravenscroft: So the legacy is that it moved the conversation on from Pomo boxes to shards?

Peter Eisenman: The most iconic architect today is Bjarke Ingles. And he is a shard architect. I mean, you know, he's not a philosophy major. He's not interested in social movements. He's interested in plying his trade and the icons that he plies are shards, they're not boxes, they're not decorated sheds. So I would say that he is the legacy.

Tom Ravenscroft: And what about how it impacted your legacy?

Peter Eisenman: Charles Jencks was a force of nature. And Charles was playing this up. I mean, he had Michael Graves on one side and Frank on the other side and me. I appeared often in Charles Jencks' work. But I don't think I'm going to be remembered for the Decon show. We'll see.

Tom Ravenscroft: Why do you think people call Wexner or the city of culture deconstructivist buildings?

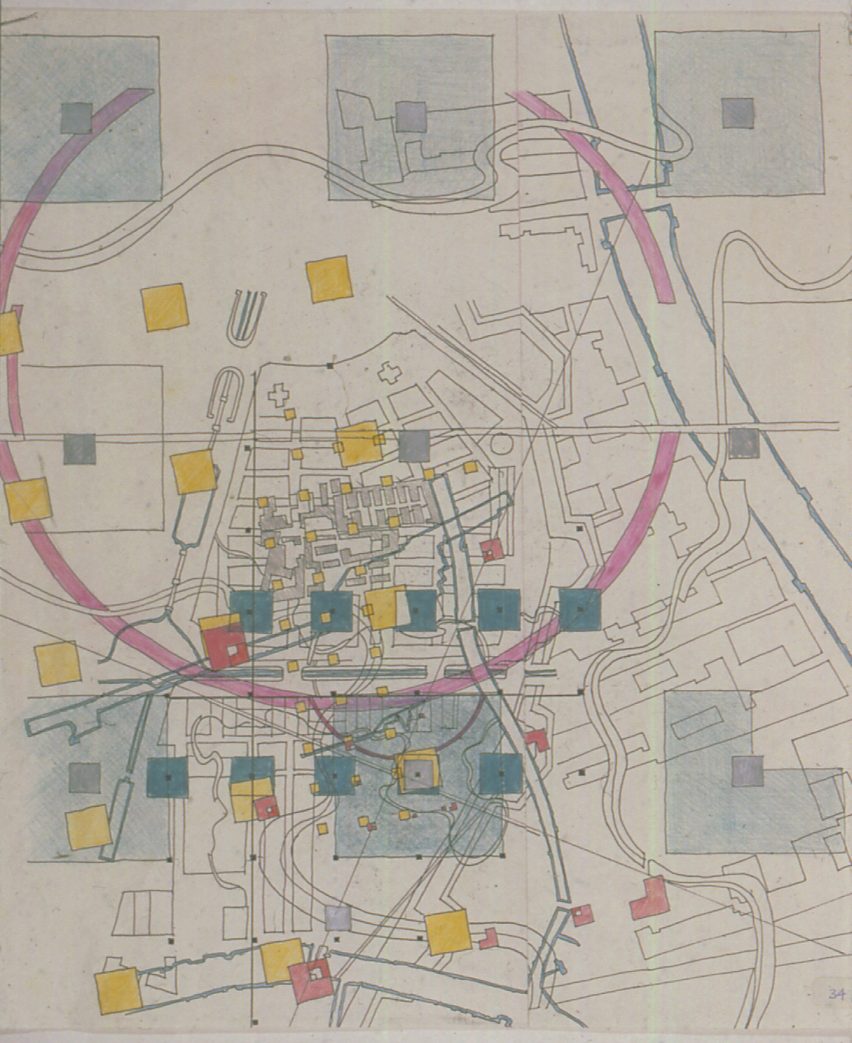

Peter Eisenman: People just don't see well. Go to the city of culture, it has nothing to do with deconstruction or deconstructivism. It's an earth project. I'm interested in the ground. I'm interested in how the ground works with buildings and I love Santiago. I think it's a really iconic project. But nothing to do with decon.

Tom Ravenscroft: And what about Wexler, as that is often described as deconstructivist?

Peter Eisenman: Tom, I can't help what people say or think. Okay. Whatever they want to say or think they can, as long as they spell my name right.

Deconstructivism is one of the 20th century's most influential architecture movements. Our series profiles the buildings and work of its leading proponents – Eisenman, Gehry, Hadid, Koolhaas, Libeskind, Tschumi and Prix.

Read our deconstructivism series ›