"Cities born fully formed are simply bad ideas thrown at the world"

Proponents of the built-from-scratch smart cities emerging around the globe fail to understand that communities cannot be created through technological innovation, write Adam Scott and Dave Waddell.

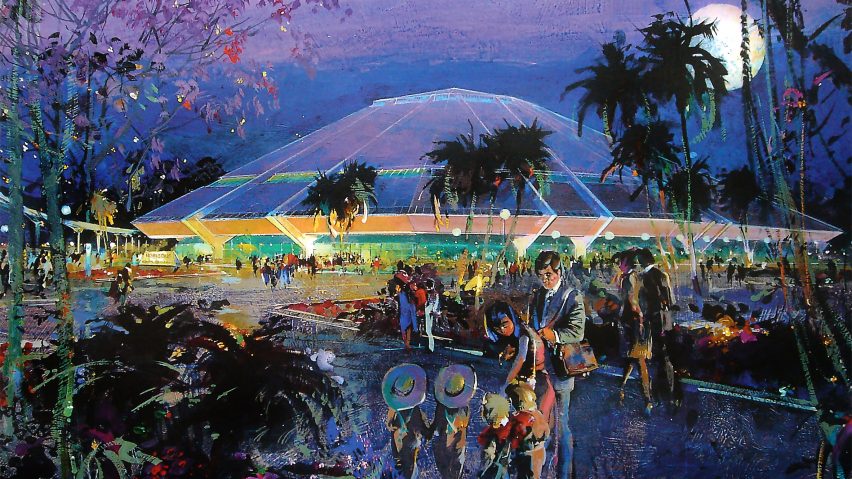

As he lay dying of lung cancer in his hospital bed in 1966, Walt Disney used the ceiling panels as a grid for the design of his city of the future. EPCOT, or Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow, was the pioneering animator and film producer's final obsession.

Planned as part of the Disney Florida Project near Orlando, EPCOT was to be an ever-improving radial garden city built from scratch, accommodating 20,000 people. It would comprise a domed 50-acre business district, underground transportation, an automated rubbish collection service, and carefully delineated residential, commercial, and recreational zones.

"It will be a planned, controlled community," explained Disney. "There will be no retirees; everyone must be employed."

The city owned and managed by Disney and partners, its citizens would be required to forego democratic rule and the right to own property in return for the privilege of living in a city free of slums and full of homes for "modest rent", underwritten by nuclear family values and always at the cutting edge of technological innovation. "It will be a planned, controlled community," explained Disney in a film made just before he died. "There will be no retirees; everyone must be employed."

That EPCOT never got built we owe to Disney being a heavy smoker. Had he lived, it's unlikely he would have been deterred. As it was, the corporation managed to extract from the Florida legislature almost everything required to begin construction, and only lacked Disney's drive to finish the job. In its place, we have Disney World's Epcot theme park, which borrows heavily from EPCOT in terms of ideas, particularly its belief in the all-conquering power of progress, always non-ironically couched in a nostalgic vision of small-town America.

That said, The Walt Disney Company did not altogether fail to follow through on elements of its founder's vision for the creation of a masterplanned community. The Floridian town of Celebration is as close as it gets to a real-world attempt to realise Disney's nostalgia for his own childhood.

Founded in the mid-1990s and located on that self-same land purchased by the corporation as part of the original Florida Project, the once Disney-owned Celebration is not EPCOT's community of unrepresented progress-driven renters. On the contrary, it is a community of well-off homeowning residents, variously attracted by the lure of Disney, the dream of small-town living, and the surety of a wise property investment. Like most of middle-class suburban America, there is a lack of employment, affordability, and diversity, a paucity of walkable everyday services and retail outlets, and a top-down form of governance.

The reader will be forgiven for believing that we are at the end of the story. Sadly, it has only just begun. Disney may have died and with him the will to make EPCOT happen. The madness, however, lives on.

Much of what Disney envisaged for his experimental masterplanned community is the ideological driver at the centre of a new wave of city-building

Today, much of what Disney envisaged for his experimental masterplanned community is the ideological driver at the centre of a new wave of city-building. The smart or U (for "ubiquitous") city is very much his thing, particularly the sort that begins from scratch, that is an ingeniously engineered kit of parts, and that has solved the problem of "mess".

The fully fledged pioneer of the EPCOT-plus city is South Korea's New Songdo. Promising its citizens "an unparalleled quality of life as technology, resources and innovation come together to create a world-class international community", it's underpinned by a package of "smart services", managing everything from the home to traffic to health, and is so technologically advanced as to have done away with the need for so-called "3D" – or "dirty", "dangerous" or "difficult" – industries. It is, say its developers, the world's first "city in a box", costing in the region of $40 billion.

Truth is, world first or not, with no manufacturing and municipal service industries to speak of, Songdo doesn't feel like a city. Seduced by their own technological knowhow, its creators blunder in thinking the complexity of a real city can be replicated by a vast and predetermined system of input-output solutions.

Similarly, they mistake Songdo's citizens – much like Disney does in his vision for EPCOT – for functionaries whose desirability is measured on the same input-output basis as the rest of the city. They've failed, claims author and architect Rachel Keeton, to create the "truly smart city", which as well as attending to "every level of society", ought to address "the parts of the city that defy definition", leave "room for spontaneity, flexibility and grassroots initiatives" and welcome diversity and transparency.

As an EPCOT-type city of the masterplanned community, Songdo's no one-off. Like Disney, who preferred to invest in an EPCOT rather than apply his prodigious levels of creativity to solving Los Angeles's urban sprawl rather than retrofit the cities we have, the favoured solution is often to start over: there are currently, says the writer Wade Shepherd, 120 city-sized projects taking place in 40-plus countries, a development that will see Earth's urban environment more than double over the next century.

These largely U-cities are considered much the cheaper and easier option: there are fewer established cultures to work around, through or with; there's no existing infrastructure to get in the way of the computing substructures deemed critical to these cities' systems and functions; and the regulations that might usually act as a check on the designs of developers are thin on the ground.

They'll have no economic reason for existing, lack any form of identity and culture

Ironically, it's exactly these reasons that serve as clues to the relatively poor success rate of the built-from-scratch city in achieving high-tech masterplanned utopia. Unless an urgently constructed answer to a gargantuan hole in the market – and able to adapt to changes in that market – cities born fully formed are simply bad ideas thrown at the world.

Some may stick, most will not. They'll have no economic reason for existing, lack any form of identity and culture, and likely have to suffer the outcomes of their creators' predilection for technology as answer to all problems. Lonely, boring, empty monuments to technical wizardry, they'll be like like Songdo or India's Lavasa or China's Ordos: living proof that communities can't just be conjured out of thin air, and that the city facilitates rather than designs the life it holds – as Walt Disney will no doubt have discovered, had he lived to drive EPCOT into creation.

Adam Scott and Dave Waddell are authors of The Experience Book, published by Black Dog Press and released in September 2022. This article is an edited excerpt from the book.

The image is by Ryman via Flickr.