Reconstruction of the Szatmáry Palace by MARP

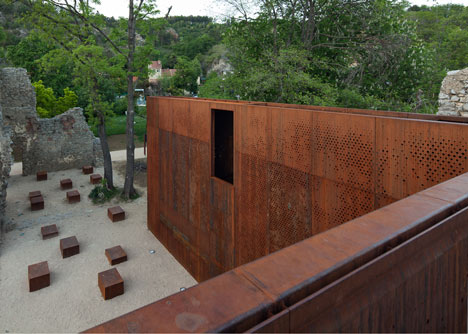

Budapest architects MARP have replaced the missing corner of a ruined Renaissance palace with a Corten steel lookout point.

The L-shaped structure is part of a renovation of the ancient site in the city of Pécs, Hungary, which was almost completely destroyed. The architects stabilised the site and added new elements, including the lookout point, a low-level stage for open-air theatre and Corten steel seating blocks.

"We chose Corten steel as the primary material of our intervention to make the new structures significantly distinguishable from the older parts," architect Márton Dévényi told Dezeen. "The old remaining structures had been so incomplete for centuries that we did not want to rebuild them, we preferred to show their absence."

The lookout point offers vistas over the Tettye valley, similar to those that the original two-storey palace would have enjoyed, while an aperture in the steel wall frames views of the internal courtyard.

Visitors ascend a staircase hidden within one wall and emerge on a walkway that runs along the length of the adjoining wall. A perforated pattern allows light to permeate the structure and filter into the staircase.

Photography is by Tamás Török.

Check out our Pinterest board for plenty more projects made from Corten steel.

Here's some more information from the architects:

The reconstruction of the Szatmáry Palace

The existing ruins of the renaissance Szathmáry Palace is one of Hungary’s most valuable protected monuments. The palace is situated in the city of Pécs which is one of the oldest town of the southwestern region of Hungary with long historical background. The ruins are located in a park of Tettye Valley in the northeast part of the city, where the dense historical urban fabric meets nature. The valley rises almost from the heart of the city, offering a magnificent view of the city from the top. Bishop György Szathmáry (1457-1524) built his own Renaissance style summer residence here at the very beginning of the 16th century. The palace must have been a two-storey building with inner patio, made of local stone. It was said to have been a U-shaped building arranged around a courtyard open towards the South, that is to say, towards the city. A former archeological excavation confirmed that the Bishop of Pécs had a building with inner courtyard built that was rebuilt a number of times later. During the long occupation of Hungary by the Ottoman Empire from the mid-16th century, the palace housed probably a Turkish dervish cloister. This is when the south-east tower must have been built that is still untouched. After the Ottomans had been driven away, the building was left empty and its condition became worse and worse. At the beginning of the 20th century, one part of the building was demolished, and certain openings were strengthened with arches, thus providing a sense of romantic ruin aesthetics. Until recently the ruin was used as a background scene for a summer theatre. Despite the long history and its superb location, the palace in its bad condition was not able to fulfil the proper role following from its historical and architectural importance.

In 2010, it was Pécs, Essen and Istanbul that were awarded the title of European Capital of Culture. As part of this, a priority project focussed on the renewal of public areas including Tettye Park. This project provided an opportunity to put the ruin in a new context and the park could be present in its redefined way as a whole. The ruin in its dense complexity carries a number of qualities, therefore the designers of the intervention studied the current context and condition of the ruin as a starting point.

The Szathmáry Palace are, mostly, ruins of a building, but today this quality does not say too much in itself. It does not particularly reflect a significant renassaince feature. Obviously it lacks the architectural details we know very little about (few of the renaissance stone fragments kept in Pécs can be attributed to the building in Tettye). So it can be said that the architectural reality of the ruins continue to exist through the spatial relations generated by the remains of the wall. However, this shows a very mixed picture caused by natural and human erosion. The volume of damage at the southeast corner is so big that one can hardly picture the supplement of the ruins.

At the same time, the badly damaged ruin, particularly due to the neglected state of the park, appeared as a picturesque landscape element in the valley of Tettye. Pre-war postcards represent the atmosphere of a nice, picturesque tourist destination which undeniably rule the whole landscape. However, the abandoned park began to re-conquer the ruin so much that during high season, the character of the ruin can hardly be made out. From certain angles, it looked like a geological creature. This feeling has still remained if one looks at the ruin closely due to the intense erosion of the former southern side of the building. The image of the picturesque ruin is emphasised by the strengthening arches made through the early 20th century.

The third important peculiarity about the building is that the originally closed inner space of the palace has continued to be part of the park’s public areas today, dissolving the former differentiation between the landscape and the building. Thus the ruin has gained a public space quality in the meantime. Interestingly enough, the open-air performances of the summer theatre set in the ruins emphasised this feature even more.

The reconstruction programme of the Tettye Park basically made it unavoidable to re-define the role of the palace ruin as an emphatic landscape element and architectural monument. When defining the interventions, our main aim was to avoid overwriting the intellectual layers as well as the quality resulting from the ruin’s complexity. The starting point was to accept the existence of these even if the layers were developed either through centuries or just a few decades. At the same time, it was unavoidable to revise and ’retune’ the quality and the meanings carried by the ruin.

During the course of the architectural interventions, together with the monument protection authority, the ruin’s wholescale floorplan and its partial spatial reconstruction was carried out based on the scientific results of the archaeological excavations that preceded the design phase. During the excavation, the base walls of the southern wing believed to have been missing for a long time were discovered, which seemed to support the hypothesis that the building did not have a U-shape. As a result of the excavations, we were now able to draw the ascending wall parts and construct the original floorplan. What we basically did during the reconstruction of the floorplan was to repair the floor level inside the external outline of the whole of the original ruins, and we also attached retaining walls along the eroded southern side and the south-eastern corner, behind which we filled up the eroded ground up to the floor level. This supporting wall has a stabilising role in stopping the erosion that resulted in the sliding. The original floorplan is marked by the walltrace.

During the local spatial reconstruction, we designed an L-shaped, steel structure building part that had been missing from the south-eastern side, which includes a look-out tower and stairs leading to it, as well as a technical facility required for theatre use. It is important to mention that the new construction did not mean to be a formal reconstruction (the latter one was not an aim in fact and the amount of data that was available was insufficient), therefore it does not repeat the original mass properly. What happened instead was that we wanted to create such a mass in the place of the former wall corner that strengthens the building character of the ruin as opposed to its ruin character, framing the city view along with the current corner resembling it to the act of viewing out of a building. On the territory of the ruin, no more reconstructions were done, that is to say, we did not mean to ’complete’ the ruin. Evidently, the look-out tower offers a fascinating view of the city, but at the same time there is a nice view too to the inner part of the ruin, making the floor plan reconstruction neat and revealing.

As a part of the floor plan reconstruction, we re-defined the ground surfaces inside the outer walls of Palace, referring the former usage of spaces: the inner patio became a green lawn zone, while the other older inner areas, where the inner rooms were, received a surface course of mineral rubble of local stone granulations. As part of the interpretation of the ruin’s space as a public space, we applied surfaces that refer to the current public space use rather than to the original floor carpet. In the former inner space of the ruin’s Western wing, a new carpet-like stage was completed for theatrical purposes, rising above the surface level very slightly. The new corner construction, the stage and the street furniture (sitting facilities) all received the same Corten steel carpet.

As part of the reconstruction of Tettye Park, both the ruin’s immediate and distant environment have been renewed. Having replanted the green area around the ruin, the formerly covered, fragmented building that could be characterised as a more unified, magnificent whole has managed to regain some of its original character. We also managed to restore both the physical and intellectual layers that contribute to the ruin’s complexity through applied interventions. It was also an aim to rather define new directions to its future destiny when we placed the parts endowed with the remaining meanings in a new context. Furthermore, the whole area could become a new, exciting part of the city context, in which the re-defined palace ruin plays an outstanding role. Through the re-arrangement of the green surroundings, which included the removal of the traffic located south of the ruin, we created a triple terrace system that defines the centre of the Tettye valley in this place again.

Architects: Marp, Budapest

Márton Dévényi, Pál Gyürki-Kiss

Assistants: Ádám Holicska, Dávid Loszmann

Landscape planning: S73, Budapest

Dr. Péter István Balogh, Sándor Mohácsi, János Hómann

Structural engineering: Marosterv, Pécs

József Maros, Gergely Maros

Steel construction planner: J.Reilly, Budapest

Zoltán V. Nagy, Péter Bokor

Electrical Planning: LM-Terv, Pécs

Gábor Lénárt

Mechanical services: Pécsi Mélyépítő Iroda, Pécs

Erzsébet Bruckner, Ferenc Müller

Competition phase: 2007

Design phase: 2008-2010

Construction: 2009-2011

Gross area: 1040 m2

Client: City of Pécs

Photos: Tamás Török

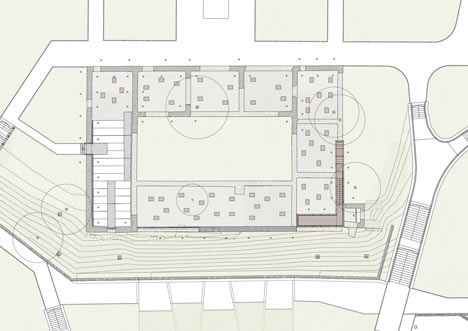

Above: site plan

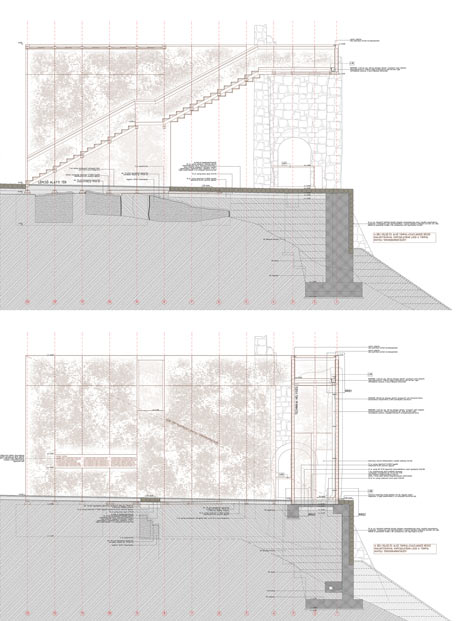

Above : section

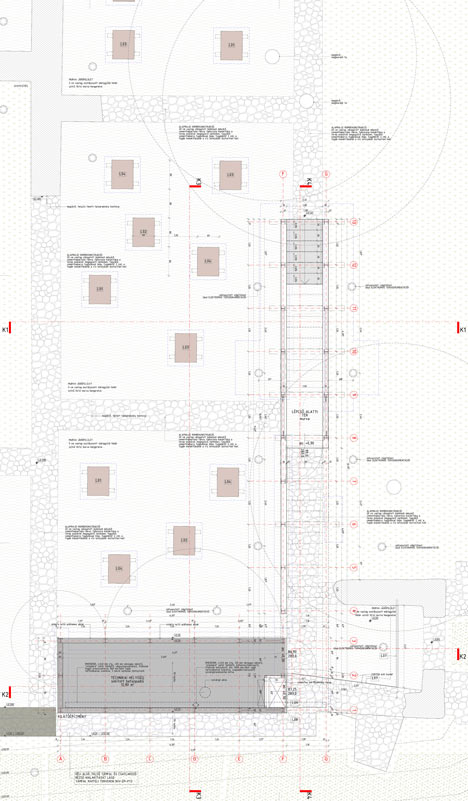

Above: floor plan

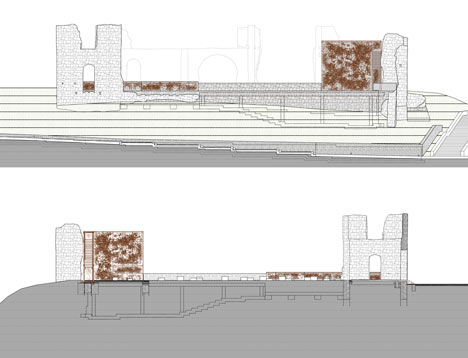

Above : elevations

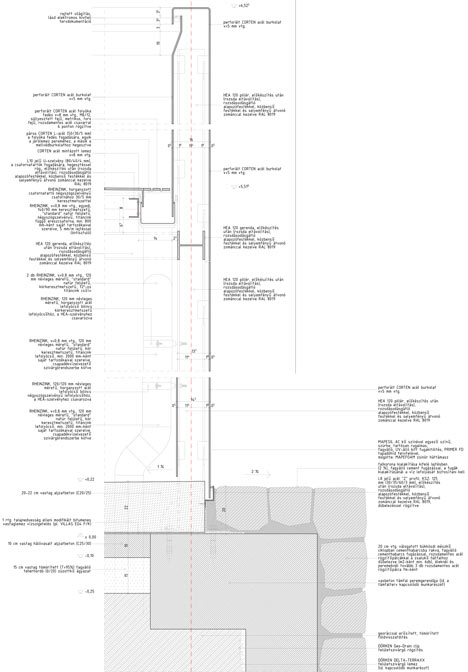

Above: details

Above : axonometry