"Zaha stood out from the start" says son of former AA head

Zaha Hadid 1950-2016: Zaha Hadid was "part of a mini-rebellion" as a student at London's Architectural Association, setting the tone for the career that followed, says Nicholas Boyarsky, son of former AA director Alvin Boyarsky. In this exclusive interview, he shares some of the drawings from his father's collection, and remembers growing up under Hadid's influence.

Alvin Boyarsky was director of London's Architectural Association from 1971 to 1990, a period that saw architects including Hadid, Bernard Tschumi and Rem Koolhaas pass through the doors as students and young teachers.

His son spoke exclusively to Dezeen following Hadid's sudden death on Thursday at the age of 65.

"Zaha stood out from the start," Nicholas Boyarsky told Dezeen. "She would, for example, make her own clothes by stapling cloth together."

"She was part of a mini-rebellion against the prevailing early 70s ethos in architectural education when many students did not really draw or design but talked instead of megastructural systems and processes, alternative lifestyles and so on," he said. "Zaha and her friends went to Alvin and demanded to draw architecture, and Alvin set them up with an independent studio. I guess the die was cast from that point."

Hadid joined the school as a student in 1972, where she met Alvin as a first-year student. It was there that she met Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis, who would go on to set up OMA.

Alvin Boyarksy and Hadid remained close friends until his death in 1990, and Nicholas said his father was "instrumental" in the architect's early career.

"She would come to the house and we would all go on what I guess would now be called urban explorations," he remembered. "We would drive in my parents' little Mini to the abandoned Royal Docks and break in to experience the huge post-industrial wastelands."

"I remember particularly when Zaha won the Peak competition in Hong Kong, and the Barrel Vault to the rear of the AA became a painting studio to prepare for the exhibition and publication," he said. "It was as if all the resources of the AA were diverted to one cause."

Nicholas – who now runs his own practice Boyarsky Murphy Architects with his wife Nicola – also told Dezeen about his own memories of being part of Hadid's unit at the AA and later of working in her office.

"We would have tutorials in her tiny house in Kynance Mews in the early hours whilst watching the movie American Gigolo over and over and eating wonderful food," he said.

Over the years, Hadid gave Nicholas' father a selection of her own drawings, including a competition entry for the residence for the Irish prime minister from 1980 and a 1988 drawing of a table she produced for a client.

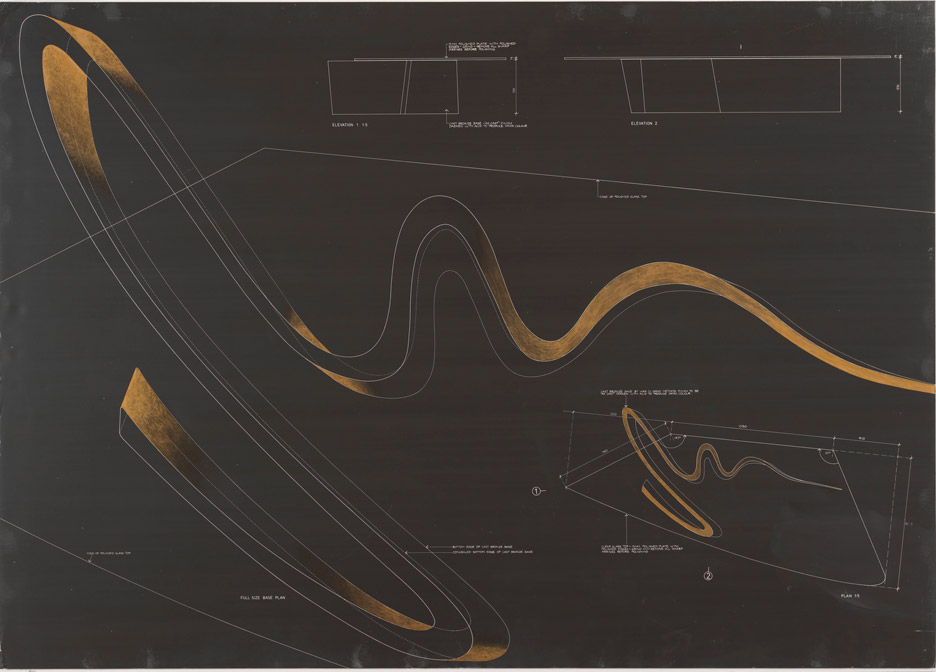

"[The drawing] from 1988, is a photographic negative print with hand-applied bronze paint on paper called Sperm Table," Nicholas told Dezeen. "It is self-explanatory! It is typical of Zaha's wicked sense of humour, carried through exactingly."

"This small sample of drawings typifies the way that Zaha developed and tested her vocabulary and skills through many different media and drawing techniques," he added.

Alvin Boyarsky's collection includes others drawings he was given by architects including Frank Gehry, Daniel Libeskind, Rem Koolhaas, Lebbeus Woods, Eduardo Paolozzi, Coop Himmelblau and Bernard Tschumi.

The collection has been on show across North America as part of an exhibition titled Drawing Ambience: Alvin Boyarsky and the Architectural Association. The drawings are due to be shown next in Europe and then Japan, and are also showcased in a book of the same title.

Drawings courtesy of the Alvin Boyarsky Archive.

Read the transcript from our interview with Nicholas Boyarsky:

Olivia Mull: What was the relationship between your father and Zaha like? Can you explain how they met?

Nicholas Boyarsky: Zaha must have first come to Alvin's attention as a first-year student. She was part of a mini-rebellion against the prevailing early 70s ethos in architectural education when many students did not really draw or design but talked instead of megastructural systems and processes, alternative lifestyles and so on. She always spoke in disbelief and exasperation (even at her Royal Gold Medal lecture this February) about the bus project in Ching's Yard where students customised a double-decker bus that would travel around Britain bringing new ideas to architectural schools. Once constructed, they discovered that they could not get the bus out and it had to be craned over Bedford Square.

Zaha and her friends went to Alvin and demanded to draw architecture and Alvin set them up with an independent studio. I guess the die was cast from that point. Zaha stood out from the start. She would, for example, make her own clothes by stapling cloth together. They became increasingly close as she started teaching and then producing her early work, which Alvin was instrumental in encouraging and facilitating her development. I remember particularly when Zaha won the Peak competition in Hong Kong and the Barrel Vault to the rear of the AA became a painting studio to prepare for the exhibition and publication. It was as if all the resources of the AA were diverted to one cause.

Zaha often came for dinner with my mother and father at their home. There are many many stories that Zaha would recount about her relationship with Alvino, as she called him, over the 25 years following his death in 1990. One, that she didn't know about, was how Alvin often used to say of her admiringly: 'She must really be Jewish, the way she swears' – this was highest praise.

Olivia Mull: When did you first meet Zaha and what are your strongest memories of her?

Nicholas Boyarsky: Probably around 1982 before I started to study architecture. She would come to the house and we would all go on what I guess would now be called urban explorations. We would drive in my parents' little Mini to the abandoned Royal Docks and break in to experience the huge post-industrial wastelands.

I really got to know her when I joined her Unit 9 trip to Moscow and Leningrad to visit Constructivist buildings in 1983. This was fabulous, the trip was also joined by Nigel Coates, Madelon Vriesendorp, Zoe Zenghelis, Rob Cole, Lisette Khalastchi, Sumaya and many others. We would stay up all night drinking vodka and Zaha would tell wild tales and sing and laugh.

Her students from this period such as Mya Manakides, Alastair Standing, Brian Ma Siy, Aris Zambicos, and later Kar Hwa Ho, remained to this day some of her closest friends alongside Kathy Jenkins and Ban Shubber.

A few years later I joined her unit, which was totally crazy. We would have tutorials in her tiny house in Kynance Mews in the early hours whilst watching the movie American Gigolo over and over and eating wonderful food prepared by Kim Lee Chai. Later I worked in her office for a spell. She was always incredibly generous, inclusive and supportive.

Olivia Mull: Can you briefly describe each of the drawings and what they show?

Nicholas Boyarsky: The first, from 1980, is an ink drawing of Zaha's competition entry for the Residence for the Irish Prime Minister, Dublin. Its an extraordinarily dynamic drawing with many different projections showing volumes crashing into or over an inhabited walled garden. Zaha is here first developing her style following her more rectilinear OMA-inspired projects.

The second, from 1984, is a hand-applied gouache and ink wash called The World (89 Degrees). It is a study for a larger painting that was exhibited at her Peak Show. This is a composite drawing that shows all her projects to date from her fourth and fifth year projects, the Tectonic Bridge and the Museum of the 19th Century, to the Irish Prime Minister's House, her entry for the La Villette competition and her scheme for the Peak.

The third, from 1986, is of the Kurfurstendamm Office Building, West Berlin. It is a study for a small office building on a narrow vacant plot at the end of a block. It is typical of the way that Zaha would study and develop the form of a building through a multitude of perspective studies, that were often conceived as an evolving series of rotations. Colour and washes were the applied to emphasise the layered forms.

The fourth, from 1988, is a photographic negative print with hand-applied bronze paint on paper called Sperm Table. It is self-explanatory! This was part of a series of furniture pieces that were produced, as one-offs I believe, for a client who did not like them so they ended up in Zaha's flat in Courtfield Gardens. The Sperm base was cast from bronze with a glass top. It is typical of Zaha's wicked sense of humour, carried through exactingly.

Olivia Mull: How do you think these early drawings relate to her built projects?

Nicholas Boyarsky: This small sample of drawings typifies the way that Zaha developed and tested her vocabulary and skills through many different media and drawing techniques. In particular they exemplify the key role of her hand in all her work.

Olivia Mull: Can you describe this period that Alvin was chairman of the AA and the environment?

Nicholas Boyarsky: Others can do this better than me, and more critically, but it was not only Zaha that Alvin encouraged and championed. Think also of other homegrown AA talents such as Peter Wilson, Nigel Coates, the NATO group, McDonald and Salter, even Bernard Tschumi.

Olivia Mull: The AA under Alvin was an incubator of thought and talent, how do you think it shaped the architectural landscape today?

Nicholas Boyarsky: I am not a historian but it is interesting to reflect that, in spite of the emergence of digital tools, it can be argued that this period remains a paradigm for critical design. The growing interest in the Drawing Ambience show amongst younger generations of students would appear to bear this out.

Olivia Mull: Can you describe the collection as a whole?

Nicholas Boyarsky: There are about 50 pieces dating from 1970 to 1988. There are collages, screen prints, drawings, sketches and paintings. They were all given to Alvin. The works are by students and staff from the AA such as Zaha, Peter Wilson, Nigel Coates, Peter Salter, Alex Wall, Stefano de Martino, Rodney Place, Jan Kaplicky and so on. A wider network of his friends and collaborators is represented in pieces by Mike Webb, David Greene and Peter Cook of Archigram, Superstudio, OMA, John Hejduk, Lebbeus Woods, Daniel Libeskind, the Russian paper architects Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkivn, Coop Himmelblau, Frank Gehry, and Eduardo Paolozzi to name a few. The drawings have never been shown before as a collection. They have been touring in North America and they are to be shown next in Europe and then Japan.