"Poverty should never be an Instagram filter"

Iwan Baan's arresting images of the Kenyan school built by architect duo Selgascano are a typical example of the slum porn that has infiltrated western media, argues Phineas Harper in his latest Opinion column.

As a racist president settles into a newly gold-curtained Oval Office and a wave of xenophobia sweeps Europe, dramatic racial inequality has been thrown into stark focus. The representation of black people in the media and broader post-colonial power imbalances require urgent examination.

It is simply not possible for white people today to over-consider the incredible inheritance left to them by colonialism. It lurks in almost every part of cultural life and, while it is absurd to argue that all customs associated with colonialism are permanently tainted, the very least we should demand is a moment's reflection on why we still drink gin and tonic or IPA.

So too should we see our architectural culture in a context of latent colonialism. Architecture was deeply co-opted in colonising projects. Whether the imposition of grid plans in Khartoum, whose civic centre was laid-out to mimic a Union Jack, or the mangled version of Ebenezer Howard's Garden City theories used to build townships in Apartheid South Africa, failure to acknowledge the colonial backdrop of international architectural taste is a denial of history.

Humanitarian firms seek to both confront, but simultaneously rely on, post-colonial power imbalances

Nowhere in architecture is the shadow of colonialism more obvious than the group of practices whose work involves projects in the Global South. Often clumsily clumped together as "humanitarian" some of these firms are extremely effective, others are very flawed, most sit somewhere between.

Humanitarian firms seek to both confront, but simultaneously rely on, post-colonial power imbalances; many raise capital from philanthropic charity, others tap aid budgets or corporate sponsorship. A few harness the labour of young gap-year travellers. What's common to all is the familiar sight of largely wealthy white designers working in largely poor black contexts.

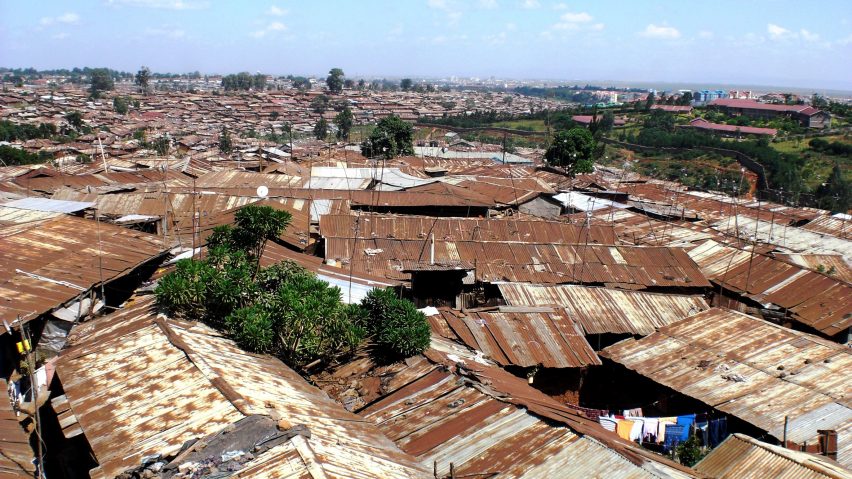

The Slum Porn chartroom on Reddit "for the appreciation of the strange beauty of all wild, informal and organic architecture" has 1,125 subscribers. This cliched objectifying language is unsurprising, as is the sight of Iwan Baan's photographs peppering the forum. Baan is a hugely popular Dutch architectural photographer courted by designers the world over. His 87,000 Instagram followers are treated to a perpetual feed of his globe-trotting snaps, often gravitating to sites of developing world poverty in which he is fascinated.

Western fixation with the architecture of extreme deprivation is not intrinsically negative, but there are prominent examples of a shallow gawping engagement which are nauseating and even exploitative.

MoMA's current Insecurities exhibition, for example, is a collection of artefacts seemingly assembled by curators googling "refugee" and "architecture" then throwing money at whatever flashed up. Displaced people are treated like a homogenous mass with little discrimination between Syrians fleeing war, Kenyans born and raised in semi-permanent city-camps and Mexicans hounded out of America by Trump.

The Kibera school is one of many projects featured on Iwan Baan's Instagram feed

Baan hit the headlines recently with the publication of his new set of photographs of Selgascano and Helloeverything's Kibera School, a two-storey structure made from scaffolding poles nestled in the largest slum in Nairobi. The project was instigated by Baan himself to replace Kibera's existing school building co-funded by the Danish art gallery Louisiana and hipster co-working wonderland Second Home.

The school itself is challenging, embodying the problematic nature of rich white designers working in the Global South. It is, of course, not a brilliant school – that truth is unavoidable and worth stating frankly upfront. It lacks acoustic or thermal insulation, its translucent polycarbonate roofing is hard to clean and it is very dirty less than a year since completion. Electrics are chaotically patched in. It is impossible to lock securely (many of their text books were stolen in a recent break-in). It fails to measure up to building regulations whether British, Spanish or Kenyan.

This is not a game-changing piece of design, yet it is presented with missionary-like piety

However, despite its flaws, the new building is surely an improvement on what came before. It is certainly brighter, more airy and unlike many Kiberan structures, stays cool in the fierce sun. The construction pumped money into the local economy – despite the fact that, as the school was first erected in Copenhagen, the materials budget went to Danish rather than Kenyan firms. Furthermore, its striking form is imbued with the glamour of rising starchitects, which has value in itself; teachers report fundraising has got easier thanks to the increased publicity. Local boys even shot a rap video there.

It is the presentation of the project however that is troubling. This is not a game-changing piece of design, yet it is presented with missionary-like piety, as a literally glowing beacon of hope for its grateful users.

This mismatch between realised quality and critical reception is symptomatic of post-colonial attitudes, which consistently reward whites beyond their achievements. You can't shake the feeling that, were this a Kenyan-grown project, instigated by unknown black architects rather than white westerners, it would have gone unremarked on.

A driving force behind the building's publicity is Baan's astounding photographs, which demonstrate man at the height of his craft. They are also deeply questionable – in one shot, taken at dusk, the new school luminesces in the background like a crystalline jewel while, in the foreground, a tiny boy stands by an open sewer overflowing with refuse. It's a stomach-churning image of western architecture draped in a moment of Kiberan squalor, appropriated as an aesthetic device.

The photography is also duplicitous. No one expects buildings to be immune to wear and we all know Photoshop exists, but consider these two images: Baan's photograph of a ground floor classroom published on 5 January show a spotless, seemingly bright space posed with happy children packing the benches.

By contrast, architect Andrew Perkins' photo of the same space taken on 17 January reveals a dark, grubby room with paint noticeably flaking off the metalwork. Flip back to original site photos of the preceding school's classroom and it becomes clear how little has substantively changed.

Humanitarian work is rarely treated seriously in architectural criticism, neither celebrated nor critiqued with sincerity

This kind of architectural photography is visual sophistry, presenting OK work as spectacular. Worse, Baan appears to have no qualms in co-opting black bodies to jazz up his shots, obscuring rather than contextualising the architecture he documents.

This practice is given credence by the media who, in rushing to publish the pictures, are complicit in uncritically reproducing the objectifying imagery. It highlights a broader problem in architectural criticism in which humanitarian work is rarely treated seriously, neither celebrated nor critiqued with sincerity. Baan and his peers are powerful image-makers but shots like those of the Kibera School, regardless of its built qualities, are pure slum porn. Poverty should never be an Instagram filter.