"Edward Burtynsky is one of the most interesting photographers of buildings"

The abstract landscapes depicted in the work of photographer Edward Burtynsky offer a frightening look at the extent of human impact on Earth, says Owen Hatherley.

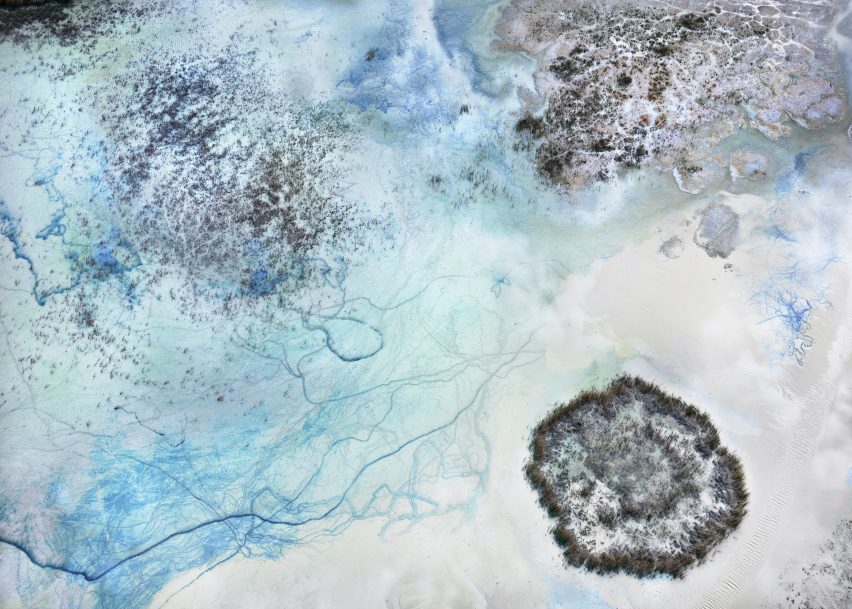

I'm in a gallery looking at several enormous photographs, though it isn't clear that they are photographs, unless you look at the captions.

Some look like abstract expressionist paintings, swirls of paint dotted and dragged along a canvas, murky and intricate but completely without realism. But then I read the caption and it says "Phospor Tailings Pond #2, Polk County, Florida, USA, 2012", or "Dryland Farming #17, Monegros County, Aragon, Spain, 2011". And what looks like an art-brut rendering of a series of daggers is "Salt Pans #25, Little Rann of Kutch, Gujarat, India, 2016".

In just a couple of photographs, you can clearly see traces of familiar objects – cars parked amidst reservoirs in the graph-like constructivist image of "Pivot Irrigation/Suburb, South of Yuma, Arizona, USA, 2011", or the clearly visible, if diagrammatic, pattern of descending paddy fields in "Rice Terrace #4, Western Yunnan Province, China".

They all look pretty, at first. But when you try and piece together what you're seeing, and try to relate it to any landscape you know, they're frightening.

They all look pretty, at first

This is Water Matters, an exhibition by Canadian landscape photographer Edward Burtynsky at Phase 2, the gallery space inside the London office of multinational engineering firm Arup.

It is the second of two recent exhibitions of his work in London, the other being part of Photo London, in which he showcased some yet more experimental work that used augmented reality to place the viewer in his manufactured landscapes.

For some decades now, Burtynsky has been one of the most interesting photographers of the built environment; not necessarily of architecture, even though he did begin as an architectural photographer, but certainly of buildings.

He has spoken about an interest in finding the biggest manmade structures possible – dams, power stations, refineries, and most recently, huge industrial-agricultural transformations of the landscape – and documenting them, often in a series, as a means to understanding, rather than ignoring, the infrastructure and production networks that lie behind every aspect of modern life.

Seeing these two shows in London, though, posed difficult questions about what it is Burtynsky does; and how work that is evidently meant to be cautionary so often looks horribly beautiful.

Burtynsky's photographs don't moralise

Burtynsky's books have straightforward names and subject matter, like Oil and Water, and their historical, analytic accompanying texts answer better than most the commonly made criticism made by Bertolt Brecht about industrial photography, that "a photograph of a factory tells us nothing about the social relations in that factory", but tells us only whether that factory is "beautiful" or not.

Instead, Burtynsky orders the images into sequences that create links between only apparently disconnected things, like ship-breaking in Bangladesh, "towns" on the freeway in the US made up entirely of drive-in chains, landscapes of burning tyres that resemble the apocalyptic paintings of John Martin, immense spaces that he calls "inverted skyscrapers", and so forth.

All are the direct result of the processes that get water into your taps and fuel into your vehicles. However, they're not polemical as such, preferring a stark, hard look at a landscape rather than an argument against it. Where there are alternatives, they can be slightly sentimental. Water, for instance, juxtaposes totally unsustainable irrigated American desert suburbs with people bathing in the Ganges.

There are moments here, as in the two films that Jennifer Baichwal has made about his work, Manufactured Landscapes and Watermark, that can verge on Brass Eye's distinction between "good science" and "bad science". But in their own right, Burtynsky's photographs don't moralise: this is what the world looks like, this is what is necessary to maintain your lifestyle, make up your own mind.

His recent works, soon to be collected in a volume titled Anthropocene, depict what he calls a "great acceleration" in the transformation of the landscape by human beings. Some of the extremely drastic work on show at Arup comes from this idea, where it's no longer clear what is human and what is natural, and the idea of an untainted Earth becomes absurd.

To document this, Burtynsky's photographs have become increasingly high-tech in the way they are produced, not necessarily in the sense of digital manipulation – the photographic fictions used by a (sometimes superficially similar) photographer like Andreas Gursky – but in the use of drones and helicopters to take the pictures in the first place, allowing him vantage points that would otherwise be impossible.

It's no longer clear what is human and what is natural

The ideas showcased at Photo London were similarly ambitious, not only the augmented reality, but the possibility of three-dimensionally printed versions of his photographs that you could enter, making these already huge and overwhelming images even more immersive, the next best thing to being there.

What has always been fascinating in Burtynsky's photographs is the same as what has sometimes made them uncomfortable – the sublime, "a sense of awe at what we as a species were up to", that you can get lost in, to the point where landfill is treated with the same panoramic grandeur as some sort of grand Victorian history painting, Phospor extraction is rendered as Jackson Pollock, and mining as Piranesi.

I wonder if that isn't undercutting the apocalyptic critique that lies underneath these images.

Bertolt Brecht's friend Walter Benjamin regarded one of the most indicative things about fascism to be an ability to regard destruction with pleasure, as a sublime spectacle. That is obviously not Burtynsky's intention – he clearly wants viewers to think about the spaces he depicts, in order to understand them – but it's often the effect, so lush and pictorial are the photographs. And they're getting more and more so, the more elaborate the technology gets. They imply that we can understand the built environment as it really exists, but only if we, like Edward Burtynsky, are able to fly over them in a helicopter or send a drone to photograph them.

It would be nice to know as well what the disasters documented by his drones look like from the ground.