Breaking Ground book on buildings by women "is both needed and problematic"

Jane Hall's Breaking Ground aims to rectify gender inequality by singling out female architects from their male counterparts. But, ahead of International Women's Day this year, Mimi Zeiger argues this corrective project could do more harm than good.

As a female writer who writes about female architects, I'm often asked to make lists of female writers and female architects. These requests mostly come from men. Well-meaning men, who want to do right by their differently gendered colleagues.

Although these asks raise the hackles on my back a little, I dutifully reply. However irritated, I've internalised my gendered role to be helpful. I want to promote my sisters-in-arms. I want to manifest an equitable field with my recommendations. And I fear that if I don't answer another panel, lecture series, or exhibition will launch into the world with pitiful representation.

I'm no martyr in this respect. Many of us regularly do this kind of professional housekeeping. Indeed, if we ignore the gender equity aspect, it's a form of gatekeeping. But it was just after a recent request for a list of women that Jane Hall's Breaking Ground: Architecture By Women landed on my desk.

The volume reinforces ongoing labours to repopulate the canon

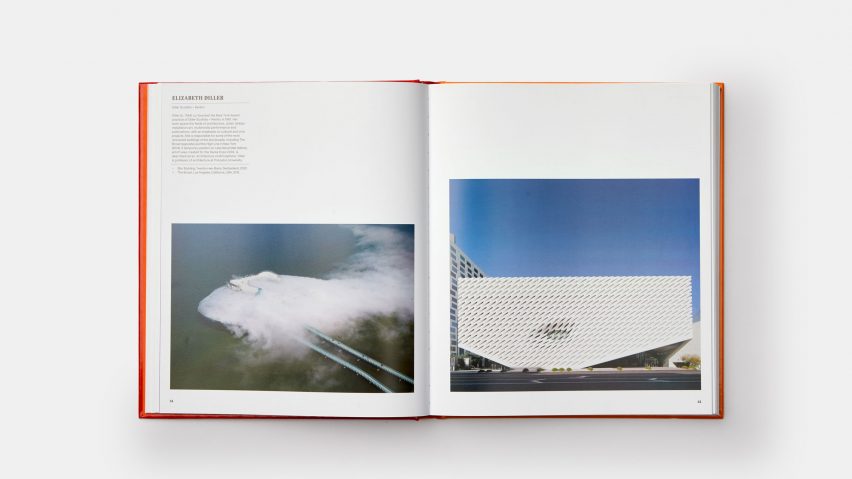

It's a beautiful volume; bold with a tomato red cover and bright orange text. Colour photographs of built work by dozens of renowned architects fill page after page, occasionally punctuated with rousing quotes by leaders of the profession, beginning with Dorte Mandrup's resounding statement: "I am not a female architect. I am an architect."

Flipping through the 223 glossy pages, I reflexively and rather cynically snorted: "It's a binder full of women," harkening back to senator Mitt Romney proverbial phrase. Breaking Ground is an inevitable sourcebook for populating lists, syllabi, and juries, and, as such, is both needed and problematic.

As a pedagogical tool, the volume reinforces ongoing labours to repopulate the canon with figures such as SOM partner Natalie de Blois – whose authorship is often eclipsed by Gordon Bunshaft and who's Union Carbide Building on Park Avenue is currently under demolition – and British modernist Jane Drew.

A majestic, double-page spread of Lina Bo Bardi's Sãu Paulo Museum of Art is a reminder of her architectural accomplishments, and she has entered mainstream consciousness just within the last couple decades.

Designs represent the persistence of trends from the mid 2000s rather than any kind of gendered authorship

Efforts were made to include a global, non-Western perspective. Works by practitioners from India, China, Latin America, and Africa are presented in the same heroic manner as those by Europe and the United States. For example, OMA's Casa da Musica in Portugal illustrates the work of OMA partner Ellen Van Loon.

It fills a full page across from Amateur Architecture Studio's Ningbo History Museum in Zhejiang Province, China. The museum illustrates Lu Wenyu's contribution to the practice she shares with Wang Shu, a contribution overlooked by the 2012 Pritzker Prize committee, who only awarded the prize to Shu.

Both photographs capture the building as an object. Shot from the exterior, context is largely cropped away and people serve the purpose of scale figures. From this perspective, the two buildings start to take on formal similarities: broad shouldered massing, angled geometries and a reductive material palette.

These designs represent the persistence of trends from the mid 2000s rather than any kind of gendered authorship. Indeed, Hall wholesale rejects the idea of "'women' as an aesthetic category".

The burden of greatness shadows the aspects of the profession that are collaborative

Breaking Ground's dilemmas lie in default format of the coffee table book and publishing's requirement to celebrate each architect as extraordinary. Otherwise, why should she be included in such an atlas?

As early as the 1970s, feminist architects identified this as a problem. Elsewhere, I've written about the landmark exhibition and book Women in American Architecture, edited by architect Susanna Torre, who is included in Breaking Ground. In both her introduction from 1977 and a more recent interview, Torre questions the notion of sole genius. The burden of greatness shadows the aspects of the profession that are collaborative.

Book publishing and media favour the clarity of individual narratives. She also stresses the structural inequality separating labour into public and private realms, thus diminishing the parts of a woman's identity that are personal, domestic, and in terms of caregiving, unequal to her male counterparts.

There's a humbling number of terrific women making really good architecture in Breaking Ground. Developers, lecture series organisers, magazine editors take note. Yet in emphasising female contributions, Hall goes so far as to single out female members of firms, isolating individual designers within practices.

Weiss, with no Manfredi, Diller with no Scofidio or Renfro, or in the case of Momoyo Kaijima, Atelier Bow with no Wow

This corrective is unsettling. The pendulum swings to the opposite side: Weiss, with no Manfredi, Diller with no Scofidio or Renfro, or in the case of Momoyo Kaijima, Atelier Bow with no Wow. However, with Charlotte Perriand or Lilly Reich, removing the modern master blocking the view proves a relief.

Last spring, around the time that Greta Thunberg was nominated for a Nobel Peace prize, writer Rebecca Solnit penned an essay entitled, When the Hero is the Problem. She focused on the false front presented by the word "singlehanded", noting that how it makes for a great and easily digested narrative of one person's efforts in the face of crisis. But it also masks the everyday efforts of many.

So, for example, in focusing only on Sweden's young climate activist, we ignore a growing climate crisis movement that is struggling to be heard. Hero culture, even in a profession like architecture, suggests that problems (design or environmental) can be cracked alone – that change is a solo accomplishment.

"The narrative of individual responsibility and change protects stasis, whether it's adapting to inequality or poverty or pollution," writes Solnit. "Our largest problems won't be solved by heroes. They'll be solved, if they are, by movements, coalitions, civil society."

The whole introduction is nuanced, with keen dissection of identity and visibility in a media age

The irony, of course, is that Hall is a member of the British collective Assemble and thus well versed in discourses around shared authorship, interdisciplinarity, and collaboration. Her introduction, co-written with Audrey Thomas-Hayes, illustrates facility with these issues and acknowledges the awkwardness of the "singlehanded" slant.

"The inclusion of a number of female 'halves' in this book does not seek to distort these unions but exists to emphasise that in many ways it is impossible to disentangle the interconnected working relationship of women from those with whom they work," they write.

Later, Hall and Thomas-Hayes recognise the complexity of ascribing authorship in practices that are non-marital unions and the societal biases that result in female partners having to prove their contributions to projects. They argue that inclusion is "intended to promote an expanded idea of how architecture in reality gets made". The thought is rightfully empowering.

Indeed, the whole introduction is nuanced, with keen dissection of identity and visibility in a media age. It says all the right things and is pretty much perfect. Still, there's a disconnect between the relatively short text and the subsequent visual rollcall of architecture by women.

The fight isn't between men and women – the goal of parity is necessary on many fronts within the field

Essayist Jia Tolentino writes about feminism and capitalism in her book Trick Mirror (excerpted in the Guardian last summer). The disconnect at the heart of Breaking Ground lines up with her critique of market-friendly feminism. She writes:

"Feminism has not eradicated the tyranny of the ideal woman but, rather, has entrenched it and made it trickier. These days, it is perhaps even more psychologically seamless than ever for an ordinary woman to spend her life walking toward the idealized mirage of her own self-image. She can believe – reasonably enough, and with the full encouragement of feminism – that she herself is the architect of the exquisite, constant and often pleasurable type of power that this image holds over her time, her money, her decisions, her selfhood and her soul."

The title of Hall and Thomas-Hayes introduction, "Would They Still Call Me A Diva?", is taken from Zaha Hadid's famous quote. The authors leave out the tail end of the question, "if I was a man?". I'd like to think of this edit as a changing of the terms of engagement. The fight isn't between men and women – the goal of parity is necessary on many fronts within the field.

Instead, this is an ongoing skirmish between the well-argued text of the introduction and the glossy pictures. Between the everyday experiences of practicing architecture and the media representations. Between a woman and images of women. Between an architect and images of architecture.