Studio Olafur Eliasson wants to be "carbon neutral as soon as possible" says head of design

Studio Olafur Eliasson is writing a no-fly rule into contracts, transporting its artworks by train and remote installing them via video calls in a bid to become carbon neutral in the next decade, says the practice's head of design Sebastian Behmann in this interview.

"We're really trying to avoid all air freight," Behmann said from his office in Berlin. "We try to ship whatever possible by train, even to Asia now."

"We put it in our contracts for commissions that we're not going to fly and we're not going to use ships unless there's no other way of doing it."

The studio started using self-built spreadsheets to track all of its emissions two years ago and discovered that transporting people, artworks and materials around the world accounted for the lion's share of its carbon footprint.

By cracking down on team flights as well as air and sea freight, Behmann hopes that the practice can get a head start on its decarbonisation goals.

"We want to become carbon neutral as soon as possible," he said. "We are currently trying to figure out a realistic scenario but we hope to do it in the next 10 years."

Studio pioneered carbon reporting in 2015

Studio Olafur Eliasson has explored humanity's relationship to the planet and its climate since it was founded in 1995, whether documenting melting glaciers, creating low-cost solar lights or suspending a giant fake sun in the Tate Modern.

As a trained architect, Behmann was originally brought on board more than 20 years ago by the practice's founder, Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson, to help realise his increasingly ambitious large-scale installations.

But it wasn't until 2015, when the studio displayed 12 blocks of glacial ice in Paris's Place du Pantheon for the COP21 climate conference, that he says the studio really began to consider quantifying its own impact on the planet.

"In our world, in our studio, I think that was the first time," he said. "We wanted to have a precise number. So if we bring in ice from Greenland, what does that actually mean? Because it wasn't very clear."

In a move that was almost unheard of at the time, Studio Olafur Eliasson worked with non-profit Julie's Bicycle to create an independent carbon report for the installation, which formed part of the practice's ongoing Ice Watch series.

In total, it found the project emitted 30 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). The vast majority of this, around 93 per cent, was down to shipping the 80 tonnes of glacial ice from Greenland to Denmark in refrigerated containers and trucking them the rest of the way to Paris.

Travel accounted for another five per cent, namely the four short-haul flights from Germany to France that were taken by the Studio Olafur Eliasson team to set up and launch the installation.

Freight is like a "black box"

This outsized impact of transport – and freight in particular – also became evident when the studio started looking at its overall carbon footprint two years ago.

"Transport is the main factor and is also the one that is the hardest to control," said Behmann, who is spearheading the studio's sustainability strategy alongside Eliasson. "Normally it's a black box. You just say pick up here, delivery there and you have no idea what happens in between."

"The only way to change how things are done is to really make a proper breakdown of how your artwork is shipped," he added. "We really had to push a lot to make that happen with our transport companies but it is in fact possible."

Based on this insight, Behmann has created charts for his team showing what modes of transport will generate the lowest emissions depending on the distance and destination, so that each journey can be assessed individually.

"Every transport is different," Behmann said. "It really depends on the possibilities and the timeframe."

In general, long-distance air and sea freight are the worst culprits, as they cannot be easily electrified and sustainable fuels are still in their infancy.

Tokyo exhibition transported entirely by train

Rail transport is the best option, and the one Behmann uses whenever possible. But it also comes with its own set of logistical hurdles, which both clients and insurance companies will need to get used to, he explained.

"It requires some patience from the client because the containers might get stuck for a week and nobody knows where they are," Behmann said.

"And insurance companies get nervous because the train might just stop somewhere where they have no control for a few days, on the border between China and Mongolia or something. But it's an easy thing to overcome, it just has to be done a couple of times."

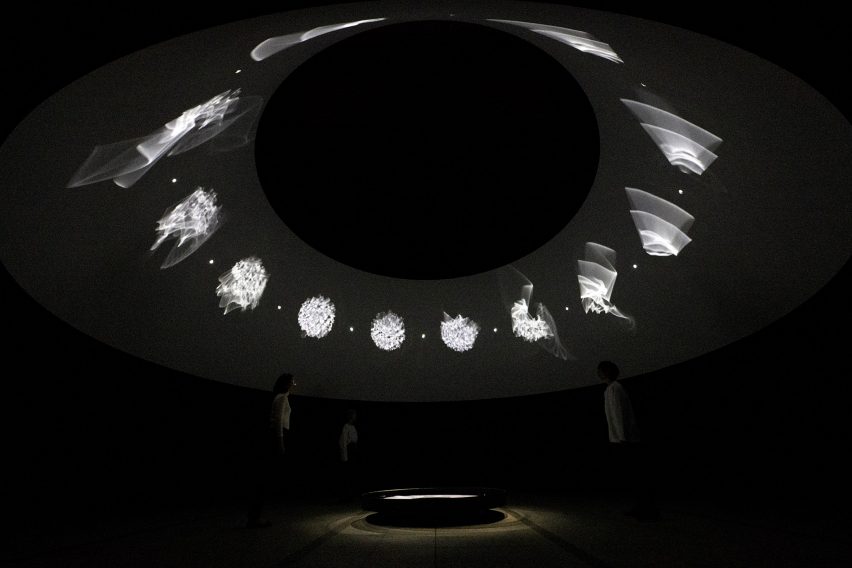

The last major exhibition from Studio Olafur Eliasson, 2020's Sometimes the River is the Bridge, was sent all the way from Berlin to Tokyo's Museum of Contemporary Art via the Trans-Siberian Railway, with only a quick boat trip needed to bridge the gap between Japan and mainland Russia.

"None of us actually travelled to Japan," Behmann said. "We did the whole installation and setup via night video conferences and Olafur didn't go to the opening as it is typically done."

Next step phasing out steel

The studio hopes to "meaningfully communicate" its full carbon footprint to the public later on in the year. But until then, this data is already being used to streamline operations internally.

"Basically, everything that we do in the studio now is tracked," Behmann said. "So every project manager, everybody who does something in the studio, has an overview of their personal impact and that gives them some obligation to do better in the next project."

"It also raises red flags in the early design process when things turn out to be just not feasible," he added. "It's the same as working with a budget, things turn out to be too expensive so you change them."

After overhauling transport, he says the next stage in reaching carbon neutrality will involve phasing out emissions-intensive materials such as steel, which is widely used for public art commissions and outdoor installations such as Studio Olafur Eliasson's Seeing Spheres due to its durability.

"Now is not the time to ship hundreds of tonnes of steel sculptures around the world," Behmann said. "So we're working on an artwork for Tokyo right now, where we're actually using zinc. And this zinc is extracted from the chimney filter of a waste burning facility."

Limits to decarbonisation effort

Packaging poses another challenge. Because, unlike food items, artworks are often stored in their crates for a number of years, making biomaterial alternatives to plastic largely unusable.

"Packaging and crating are big things where there are simply limits to what you can do," Behmann said.

"Most sustainable packing materials might only last a few weeks. If you have them in the box for longer, they start to decompose. They just don't have the lifespan and they actually start to damage the artworks."

A slew of brands including Dezeen, Danish furniture maker Takt and carmaker Volvo has started setting their own decarbonisation goals in recent years, with more than 5,000 businesses now signed up to the UN's Race to Zero campaign to help limit global warming to the crucial 1.5-degree threshold.

But art, design and architecture studios have so far been slow on the uptake, with a few notable exceptions including the practice of British designer Sebastian Cox, which he says is already carbon negative.

The top image is by David Fischer.