Parc de la Villette is the "largest deconstructed building in the world"

Continuing our deconstructivism series, we take a look at Bernard Tschumi's Parc de la Villette in Paris, one of the movement's earliest and most influential projects.

French-Swiss architect Tschumi designed the park as a deconstructed building.

"It was not about nature, per se, it was an urban moment," Tschumi told Dezeen. "I call it the largest deconstructed building in the world as it's one building, but broken down in many fragments."

Tschumi won an international competition in 1983 to design the 55-hectare Parc de la Villette in northern Paris, beating more than 470 entrants including OMA, Zaha Hadid and Jean Nouvel.

The project was part of president Francois Mitterrand's vision for the economic and cultural development of a semi-industrial district bordering the city's northeastern suburbs.

The brief called for an "urban park for the 21st century" that could accommodate a complex programme of cultural and entertainment facilities.

Tschumi's proposal for a "social and cultural park" containing 35 architectural follies intentionally departed from the classical interpretation of a park as an ordered space for relaxation.

The architect wanted to create a place for activity and interaction, without precedent, rather than designing a traditional park focused on taming nature and producing an artificial landscape.

"I wanted to create a place that people could appropriate, that they could take over and it would not, in a sense, constrain them," he said.

"Much of the strategy was about letting people invent their own way to use the park."

The follies distributed across the landscape feature forms that appear to have been broken apart and reassembled, enhancing the sense of imperfection and disorder that gives the park its distinctive personality.

"The movement of bodies in space was really important both at the large scale of the park – the cinematic promenade and all that – and within the follies themselves, which have rams, stairs, elevators," explained Tschumi.

The theoretical principles supporting the design, which were informed by the work of the French philosopher Jacques Derrida, led to it later being viewed as one of the pioneering works of the deconstructivist movement.

Derrida is known for developing a form of semiotic analysis called "deconstruction", which questioned dominant discourses in Western culture and philosophy.

This desire to analyse and disrupt established conventions influenced Tschumi's pursuit of ambiguity and belief that there is no one interpretation of form or meaning that must be adhered to.

"I am not interested in form," Tschumi once proclaimed. "I attack the system of meaning. I am for the idea of structure and syntax, but no meaning."

The park was one of seven projects included by Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley in their seminal 1988 exhibition, Deconstructivist Architecture, held at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

In the exhibition catalogue the project is described as "an elaborate essay in the deviation of ideal forms," that "gains its force by turning each distortion of an ideal form into a new ideal which is then itself distorted."

This focus on reassessing and distorting familiar forms and architectural practices recurs throughout Tschumi's work, which prior to the Parc de la Villette project had largely taken the form of theoretical drawings and written texts like The Manhattan Transcripts (1976-81).

The park was built on the former site of the Parisian slaughterhouses and wholesale meat market, as part of the redevelopment of the area in the 19th arrondissement.

Tschumi's plan was arranged around existing and proposed buildings, including the enormous City of Science and Industry museum (completed in 1986), as well as several concert venues and the Conservatoire de Paris.

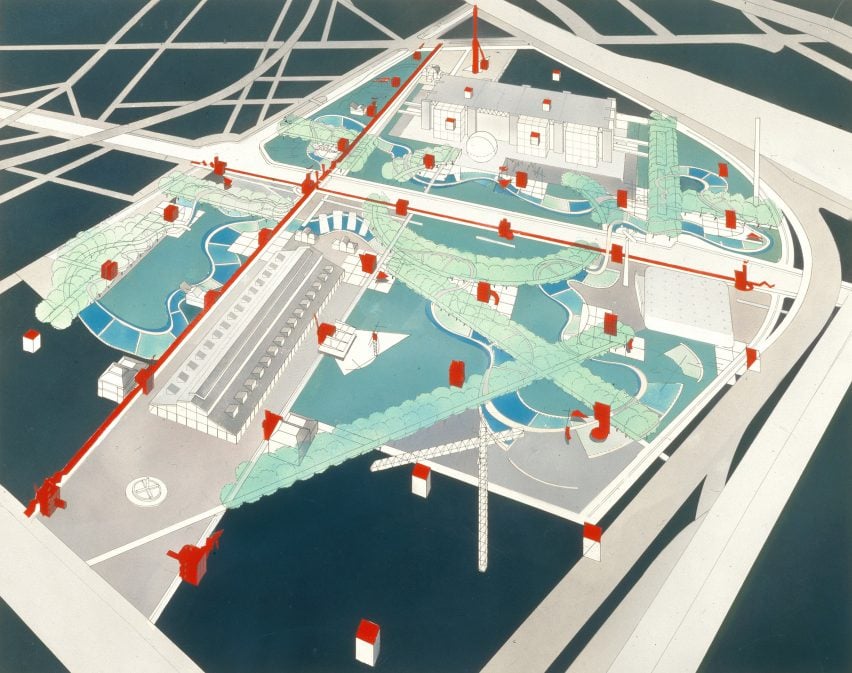

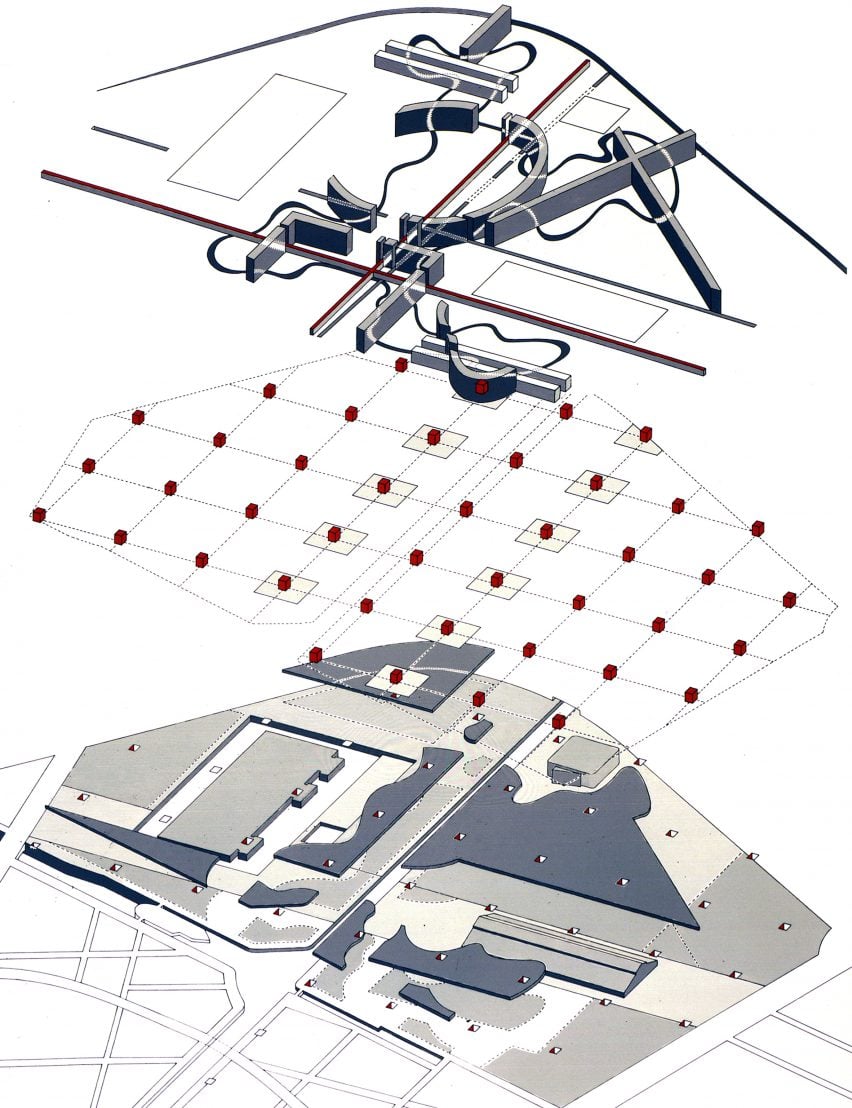

The design is based on a series of points, lines and surfaces, which references the work of constructivist artists in the early 20th century, including Wassily Kandinsky's influential book Point and Line to Plane (1926).

In the Parc de la Villette, the points are provided by the various red follies, which are arranged in a grid system of 120 x 120 square metres.

Despite the ordered distribution of the follies within the park, their differing contextual relationships with existing structures, green spaces and the two canals that traverse the site result in varied intersections and experiences.

A system of lines based on classical axes is translated into straight, curved or meandering promenades that promote movement through the park and guide users towards points of interest.

An elevated walkway follows the Canal de l'Ourcq, which crosses the site from east to west. Other paths intersect and splinter off in different directions, responding to points within the site and the surrounding area.

The park's surfaces comprise a set of circles, squares and triangles translated into green spaces and paved areas used for recreation or hosting events. These surfaces are warped to create a fractured topography connected by the twisted and broken paths.

Ten themed gardens break up the expansive site and provide opportunities for visitors to relax, interact, gather and play. These include a mirror garden, wind garden, bamboo garden, youth garden, and a dragon garden.

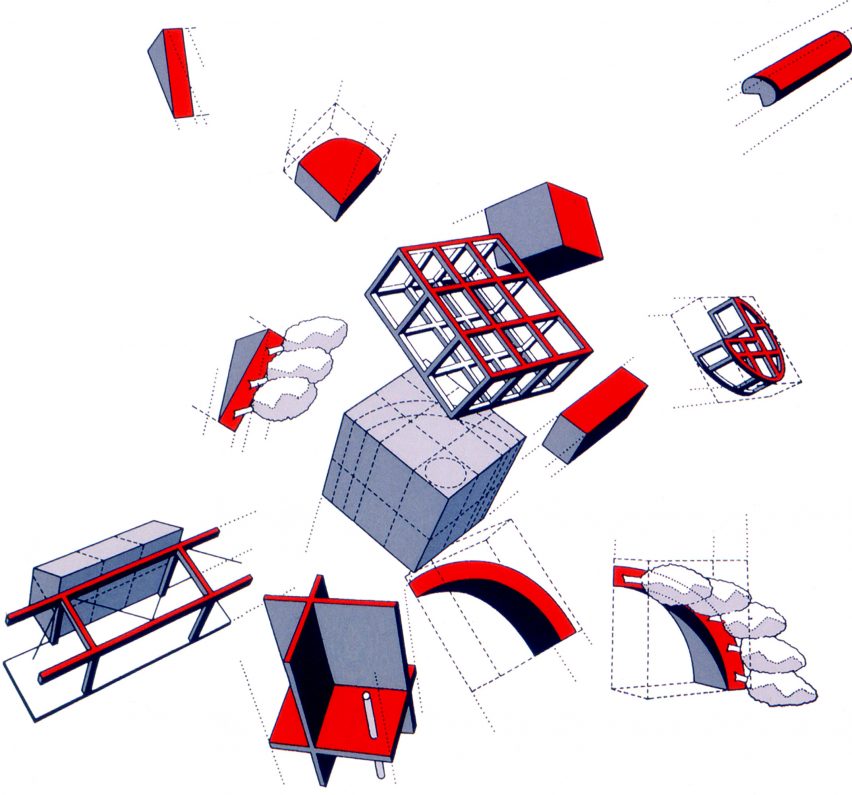

The follies positioned around the park are based on a 12-metre cube that is pulled apart into various components and then recombined to create artistic assemblages.

Each unique structure is built using concrete and red-enamelled aluminium panels. The repetition of forms and colour creates a sense of coherence and their even spacing helps visitors orient themselves in the large park.

Like the rest of the park, the follies are designed to exist independently of any historical precedents and even their functions are arbitrary, with several having been used for different purposes since their completion.

Many of the follies are purely sculptural, while others provide spaces for amenities including cafes, ticket offices, lookouts and a 700-seat concert hall.

Parc de la Villette's informal, user-defined spaces and buildings proved controversial and the park was also criticised for its vast size and lack of engagement with its historical context.

However, the project achieved the objective of redefining how a park could be designed for the 21st century. Rather than taking people out of the city, it became a part of the urban context that emphasises and promotes interaction between people and place.

Ultimately, the work proved influential as a manifestation of Tschumi's theory of an "architecture of dysjunction" that offered a new typology for urban planning based on de-structuring and de-centring programmatic requirements.

Deconstructivism is one of the 20th century's most influential architecture movements. Our series profiles the buildings and work of its leading proponents – Peter Eisenman, Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, Daniel Libeskind, Tschumi and Wolf Prix.

Read our deconstructivism series ›

The illustration is by Jack Bedford.