Nine types of street furniture that "exert an outsized impact on place and mood"

On the Street aims to draw attention to a layer of public architecture that often goes unnoticed. Here, the book's author Edwin Heathcote highlights nine types of street furniture that "slot in amid the big things".

From benches to 5G masts, On the Street: In-Between Architecture focuses on the various structures that occupy pavements in cities and towns across the world.

"This layer of objects is often unnoticed, between the bodies and the buildings, it's at a very human scale," Financial Times architecture critic Heathcote told Dezeen.

"These things, the phone boxes, post boxes, bollards and kiosks populate the city in a similar way to how we ourselves do, slotting in amid the big things."

"The effects can be radical"

Although these items of street furniture are often small, Heathcote believes that they can have an oversized impact on the feeling of our streets.

"Small interventions can exert an outsized impact on place and mood," he explained.

"The effects can be radical, think of streetlighting which opened up the city to a 24 hour life, or they can be fleeting, like the momentary relief of a seat or a drink of cool water from a fountain," he continued.

"But the best of street furniture all exists in some way to make the lives we live in public more comfortable."

"Shift from amenities to surveillance and deterrence"

The book also explores how street furniture has shifted from improving people's experience of cities to observing and controlling them.

"The most radical transformation in the world of street furniture has been the shift from amenities to surveillance and deterrence," said Heathcote.

"What was once a layer of things to enhance street life has become a more sinister network embodying the encroaching trend of surveillance capitalism, in which our data is harvested, our faces recognised, number plates recorded and activity monitored," he continued.

"The designs themselves, thick poles with cameras surrounded by spiked collars and blind-pressed metal boxes do not add anything to the quality of public space, quite the opposite, they take up pavement without giving back."

"Reminders of cities that once were"

According to Heathcote this trend, combined with the growing privatisation of public space, builds a nostalgia towards historic, often defunct, structures that occupy streets.

"As the space of the commons is eroded, as public space is increasingly privatised and as cities abdicate their responsibilities for public space to commerce and retail, these often obsolete pieces of street furniture seem to become old friends," he said.

"Post boxes and phone booths from an era when utilities were publicly-owned, manhole covers revealing the names of long-gone public companies, coal holes appearing as badges set into the pavement. They feel like reminders of cities that once were."

Read on for Heathercote's view on nine types of street furniture:

Phone box

Is there anything more defunct than a phone box? These strange spaces, transparent yet private, were once a refuge and a wonder, tiny rooms of global communication. They smelt of fagsmoke, wet coats and piss and at the end of their lives they acted as sex-worker exchanges with lurid printed cards but they were also a refuge, a truly public interior.

Mobile phones have made them utterly obsolete but, in the UK at least, those in conservation areas survive as heritage. Some are being repurposed, as mini-libraries, espresso stands and defibrillator stations.

The idea of a private room in the midst of a busy street remains curiously seductive, which is presumably why phone booths have such a rich list of appearances in the movies.

Bollard

Bollards have been around forever. Some famous examples in London and the Netherlands were made from old naval canons with cannonballs stuffed into the muzzle and stuck into the ground, an early example of adaptive reuse.

Many subsequent bollards maintained the memory of the canon in their form. Others look a little more phallic. Italy has its ancient stone versions, some going back to the Romans, most of elsewhere has cast-iron types in an almost endless array of designs.

In the mid-twentieth century, the brutalists turned them into concrete, though they proved less durable as the rebars rusted. The bollard, the most basic type of street furniture, has recently enjoyed a revival thanks to terror. City centres around the world are now studded with an array of chunky monsters in metal and concrete, objects designed to deter not traffic but truck bombs.

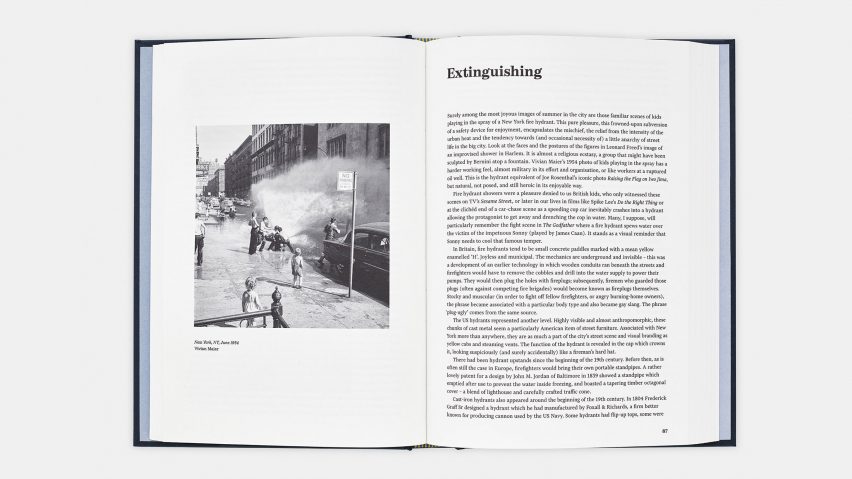

Bench

There is nothing more public than a bench. It is the most democratic element in the city. A place where, at least in theory, the homeless can sleep and the tired can rest, the contemplative can sit and the hungry can eat their sandwiches.

Perhaps that appeal has meant that designers cannot leave them alone. Constant efforts to redesign the bench mostly throw up atrocities and self-conscious 'artworks' along with the occasional glimmer of hope.

But the best benches remain designs that date from over a century ago. Think of the cast-iron-ended sphinxes of London's Embankment or the simple, sinuous lines of the municipal benches seen in Bishop's Park and many other public places.

5G mast

At the beginning of the Covid pandemic, crowds began to gather to set fire to the new 5G masts that were appearing across city streets. The new communication technology was blamed for spreading the virus.

It was a curious throwback to an era of witch trials and superstition. We are as in thrall to technologies we do not understand as the New Englanders were to the Bible four hundred years ago.

Ironically for a communications technology, these masts reveal nothing, they communicate nothing about themselves. We could perhaps understand the technology behind a phone or even a telegraph pole but these strange oversized cotton buds are sinister in their blankness. They add nothing to the public realm. In fact they get in the way, constricting already narrow pavements, impinging on the minimal space we are left after cars have taken their share. Where, today, is the metropolitan ambition?

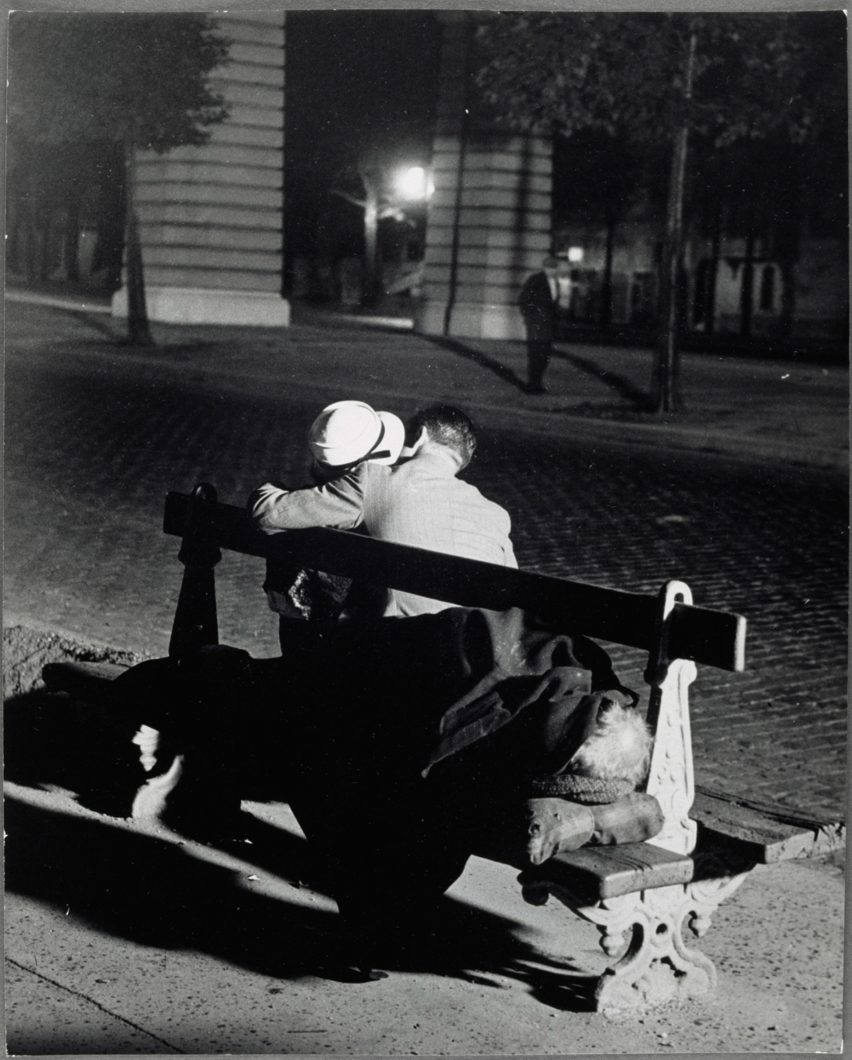

Streetlight

Street lighting changed everything. Suddenly the night opened up, creating public space that was accessible around the clock. London pioneered urban lighting's modern age with gaslit streets making the Regency city safe for shoppers and creating the consumer culture of the sparkling storefront and window shopping.

Lighting was of course only new in the West. Baghdad had streetlighting a millennium ago, while Chinese cities had wooden conduits carrying volcanic gas lit to illuminate their streets.

Previously lightning had been left to property owners, using lanterns or candles at their windows. Making it a municipal responsibility (often controlled by the police), was part of a moral campaign. It was thought that illuminating the darkest urban corners would deter sex workers from soliciting, criminals from lurking and potential revolutionaries from gathering and plotting. It did not.

Yet lighting retains its moral dimension. Anyone who has seen the fiercely bright floodlighting in an urban estate lit up like a US prison yard will have felt the stigmatisation of an illumination that makes public space look like a potential crime zone. In contrast, bouji neighbourhoods like Hampstead or St James were allowed to retain their Victorian gaslighting as heritage. Like everything else in England streetlights illuminate issues of class as well as space.

Pissoir

Baron Haussmann's rebuilding of Paris as a formal, revolution-proof city in the nineteenth century had a parallel plan to populate the streets with a layer of coordinated street furniture, from kiosks and advertising columns to pissoirs.

These latter were part of efforts to clean the city up and deter people from pissing in dark corners. Open to the elements but with the midriff obscured, they were a halfway house between full public lavatories and open urinals.

Hugely popular but prone to rust and, in summer at least, appalling smells, they also became a magnet for a queer cult, the soupeurs, who would take pieces of bread to mop up piss and eat it. Part of the city's cruising networks, a facility intended to adjust the morals of a city became known as a place of perversion.

The intent of street furniture is usually clear, the way in which it might be subverted so often less so. That women's facilities were barely even considered illustrates perfectly how gender was inscribed in the city through its language of things.

Water fountain

Fresh clean water was a wonder of the modern metropolis. In the wake of John Snow's findings that dirty water caused disease, cities began erecting fountains in huge numbers.

Partly as a means to supply safe water, partly in an effort to deter drinking, as beer was otherwise the default refreshment of cabmen, porters and workers. As public amenities they were made super-visible, carved in monumental stone or cast in heavy iron. The Wallace Fountains of Paris have become landmarks, punctuating the city with an emblem of public good. They were often funded by anti-alcohol associations. That they are now not funded at all is a disgrace.

It might be worth comparing the UK's new bottle-refilling stations. These could have been beautiful amenities, points of public gathering and symbols of a new urban ambition of sustainability and a free resource. Instead, they are plastic atrocities more closely resembling a corporate expo mascot or a failed emoji. This is where our urban ambition is.

Newsstand

Another seemingly defunct piece of communications infrastructure, the newsstand was once the dynamo of the public arena, bringing global news to the street corner. These kiosks proved hugely attractive to photographers, from Rodchenko to Vivian Maier, each seemed to capture an aspect of these curious structures with appeared like little theatres, their headlines as curtains.

Stanley Kubrick, a one-time photographer for Look magazine, captured a New York newsstand in 1945, a shot which captures the ennui and the drama, the dejected newsman, and the dramatic headlines (FDR Dead). Some survive but papers have mostly given way to souvenirs or sweets. Trevor Traynor's lovely series of New York news vendors capture their chaotic vitality brilliantly.

Memorials

The smooth steel pole seems like the blandest expression of modern engineering. Yet these posts, supporting traffic lights, CCTV cameras or street signs, often find themselves at the junctions where tragedies occur.

They are then reimagined as the sites of despair and commemoration. Photos and flowers taped to a pole in memory of a victim of knife crime or a traffic accident. Teddy bears and kids' drawings rain-blurred inside see-through plastic wallets.

Street furniture might appear to be imposed on us but we are also able to adapt and adopt, to use it as a frame for our concerns. Guerrilla knitting, graffiti, stickers, vandalism, protest, these bland things can become our public forum in the most unexpected of ways.