UCL researchers translate endangered languages into 3D-printed objects

An anthropologist and an architect from University College London have collaborated on a unique way to preserve endangered languages – by capturing their character in the form of 3D-printed objects.

Alex Pillen from the university's anthropology department and Emma-Kate Matthews from the Bartlett School of Architecture made use of parametric design software to visualise the sound and grammatical patterns of four different languages and gave them a physical form using a 3D printer.

The aim was to find a new way to document the world's endangered languages and communicate complex aspects of language that are usually lost in translation.

"We do, of course, have recordings of these languages to preserve the way they sound, while the vocabulary can be preserved in a dictionary," said Pillen. "But what is more difficult to preserve is the grammar because this is often presented in a very dry manner by linguists."

"You get transcripts, annotated with very technical terminology. But by producing the geometry of grammar in 3D, we allow people to have an immediate intuitive relationship to these languages that are under threat – or that might disappear."

The project began with Pillen looking for a cover design for her book on the Kurdish language that would roughly be "the architecture of the Kurdish language incurred through an abstract design".

To realise this idea, she went to Matthews – a PhD student focusing on the intersection of music and architecture. Matthews developed the parametric algorithm to translate the languages into visualisations using the 3D-modelling software Rhino.

The duo chose to build four models based on four languages: Kurdish, the Amazonian language Tariana, an ancient Mesopotamian dialect called Akkadian and, for comparison, American English.

They picked a speech sample to use for each, except in the case of the already extinct Akkadian, for which they used a written sample from a clay tablet.

In particular, the researchers wanted to focus on capturing the grammatical character of the languages due to the parallels they perceive between grammar and geometry.

"Grammar is defined as the whole structure and system of a language, and has been compared to a geometrical order for centuries," they write in their paper, published in the Nature journal Humanities and Social Sciences Communications.

The duo honed in on the grammatical element of the evidential – a qualifier that is added to a sentence to indicate the source of the information that is being conveyed.

According to Pillen, evidentials are most prominent in Native American, Amazonian and Aboriginal languages, which have complex grammatical structures, while English speakers have to add longer phrases such as presumably, reportedly or I was told.

In the Tariana language, speakers are grammatically obliged to indicate the source of the information they are discussing at all times using a hierarchy of evidentials, which denote everything from the speaker having directly observed something to the repeating of information relayed by someone else.

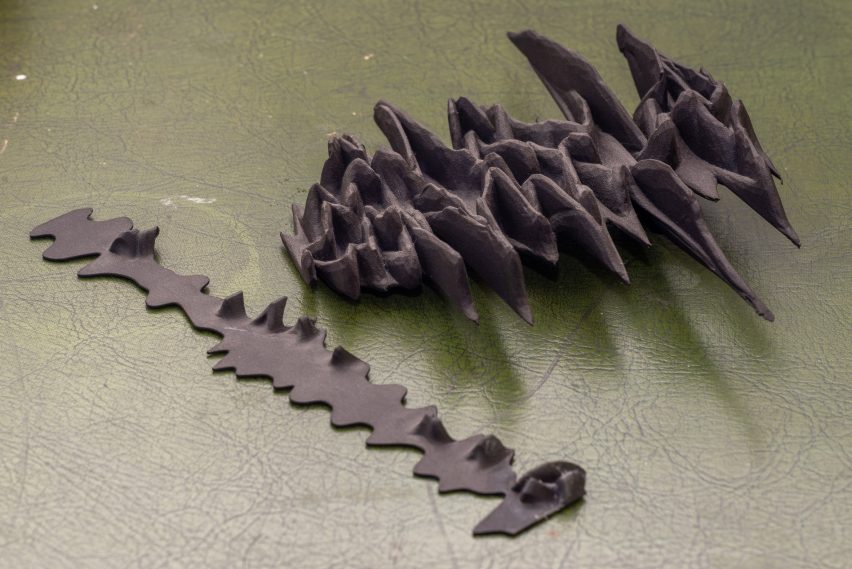

This gives the Tarianan 3D model its pattern of dramatic crests.

To translate these evidential systems into 3D space, Pillen and Matthews assigned each statement a numerical value corresponding to its evidential weight and plotted this onto the z-axis inside Rhino.

The number of syllables was plotted along the y-axis and the timeline on the x-axis, allowing the design software to turn these points into a smooth, undulating 3D shape.

Pillen and Matthews then 3D printed the designs, starting in nylon plastic before moving on to a silver alloy that better showcases the designs' intricacy and a rubber-like thermoplastic polyurethane that has a fabric-like smoothness.

The duo liken their approach to visualising the "shape" of humanity's natural languages to the envisioning of DNA as a double helix.

"The double helix of DNA and structure of virus particles are by now familiar as images that circulate widely," their paper reads. "By contrast, the shape of humanity's natural languages, and their high-dimensional form mostly remain to be explored and modelled as visual material."

"The contemporary software we have at our disposal and methods for digital design allow us to visualise the natural forms of human language."

In the future, the researchers want to expand their method to incorporate larger datasets and perhaps create moving images with evolving shapes.

They say that around 1,500 of the world's languages are at a high risk of being lost in the next century, affecting the identity and wellbeing of people from those communities.

Another recent design project that has aimed to preserve endangered languages is Typotheque's North American Syllabics typeface, which was designed to make it easier for Canadian Indigenous communities to communicate digitally.