Seven Parisian brutalist buildings that illustrate the movement's "level of experimentation"

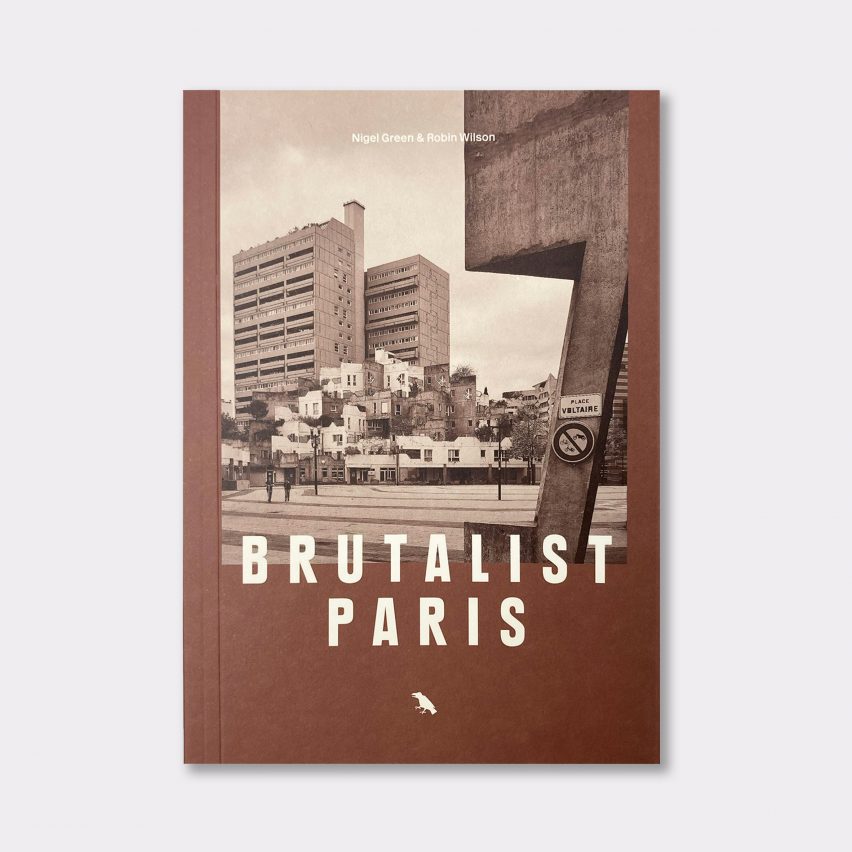

Barlett School of Architecture professor Robin Wilson has shared with Dezeen a selection of eclectic brutalist buildings in Paris that are featured in his latest book, Brutalist Paris.

Published by Blue Crow Media, the Brutalist Paris book is made up of seven essays detailing over 50 buildings completed in the 1950s through to the 1980s.

"The aim is to recognise the level of endeavour and experimentation the period involved," Wilson told Dezeen.

The text explores the social, political and cultural contexts of brutalist buildings in the French capital, and is accompanied by photography by Nigel Green.

Described by Blue Crow Media as "the first cohesive study of Brutalist architecture in Paris", the book's photographs and essays detail some of the city's more celebrated brutalist structures, as well as ones that have been abandoned and demolished.

Author Wilson was drawn to Paris's examples of brutalist architecture because of its diversity of styles and approaches to building.

The book covers a range of building types and scales, from large urban developments to intimate living spaces and brutalist projects that have now been converted.

"I wanted a discursive and comparative reading of approaches, and one which is also contextual," said Wilson.

"This hopefully gives the impression of the account as being one generated by a sense of critical enquiry rather than a straight, fact-focused history, and which also captures a sense of the many journeys that the study involved."

"Parisian architecture of the brutalist period is very diverse in style, approach and philosophy, which makes defining it quite a challenge, and of course, the building materials and technologies change quite significantly over the period," the author continued.

"Many of the architects operating in the 1960s onwards wished to break from the models of modern construction, especially in housing, of the earlier post-war period, including the influence of Le Corbusier," he added.

"There was no general consensus on how to do this, and many radical propositions emerged, not just for new building forms, but also whole new urban environments."

Wilson hopes that from reading the book, readers will gain "a sense of inquisitiveness to visit the buildings and to develop an understanding of Paris as something considerably more expansive and diverse than the familiar, historic city centre."

"Also, to get a sense of what was socially at issue in the work of design for many architects of the period, to achieve architectures that proposed new ways of living and occupying the city," the author continued.

Brutalist Paris is the first book published by Blue Crow Media, which had previously only published city maps and guides.

Read on for the author's picks of seven Parisian brutalist buildings featured in the book:

UNESCO Conference Hall by Marcel Breuer, Pier-Luigi Nervi and Bernard Zehrfuss (1958)

"The Conference Hall is an important building symbolically and technically in the early phase of Parisian brutalism, and a good example of the collaborative projects between international and French architects for new institutions of the post-war period.

"The structure for the Conference Hall was built from in-situ, formwork concrete and bears the marks of its shuttering. Nervi – an engineer – employed a single, corrugated or folded-plate, concrete shell, which allowed for the fusion of structure into the building envelope as a single entity.

"As Marcel Breuer put it, 'not only bones, but bones, muscles and skin combined.'"

Telecommunications Building by Pierre Vivien (1970)

"An unexpected brutalist objet trouvé (found object) of western Paris, the Telecommunications Building is important within our array of buildings for its singularity as a form.

"Built by the architect responsible for the post-war reconstruction of Boulogne-sur-Mer, it is employed as a Telecommunications Building but is more productively engaged with as a scale prototype (1:10) for a unit of utopian urbanism."

The Administrative Centre of Pantin by Jacques Kalisz and Jean Perrottet (1973)

"Kalisz's Administrative Centre of Pantin, now the National Centre of Dance, has been, since the outset of our project, one of our benchmark projects of Parisian brutalism.

"The original programme of the building amounted to an immensely ambitious centralisation of the administrative departments of Pantin. By 1997 the building had been returned to the state, after a period of gradual abandonment by the municipality.

"The repurposing of the building as the National Centre of Dance was completed by Antoinette Robain and Claire Guieysse in 2004, one of the very successful examples of the adaptive re-use of a brutalist building in Paris."

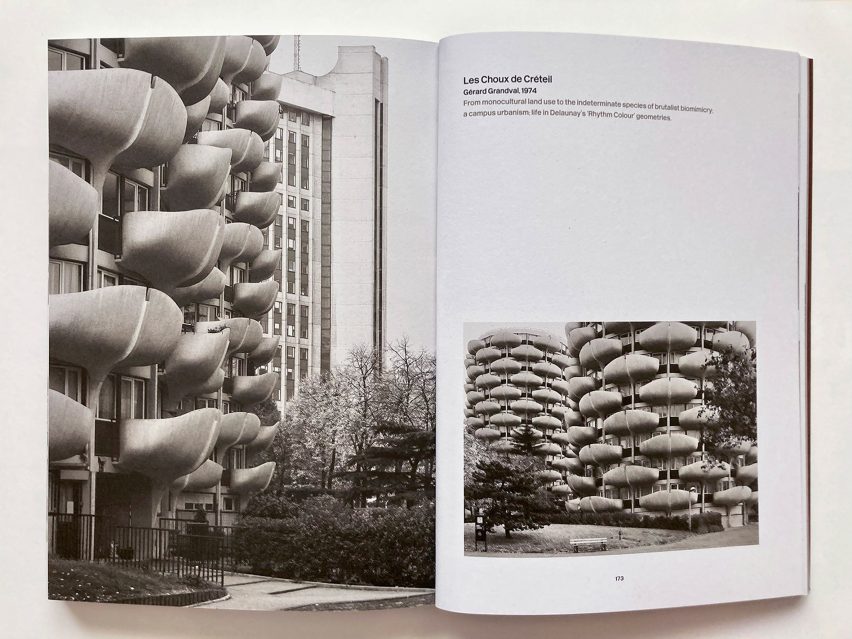

Les Choux de Créteil by Gérard Grandval (1974)

"Les Choux buildings are a brutalist social media favourite. Their promiscuous relationship with the camera lens undoubtedly derives from the combination of the volumetric generosity of the balconies and their seemingly endless repetition as mass-produced elements – a genuinely spectacular combination of industrial production with organic form.

"The name Les Choux derives from land use. Grandval recounts that there were no historical references within the original site, only the cabbage stalks of a flat agricultural landscape – there was a large Sauerkraut factory, the Choucrouterie Benoist, nearby."

Jeanne Hachette Complex by Jean Renaudie and Renée Gailhoustet (1975)

"This urban project in Ivry-sur-Seine is distinct from many of the other peripheral urban scale developments in that it involved the redevelopment of an existing town centre, rather than establishing of a new one.

"The Jean Hachette phase embodies the core aim of Renaudie's oblique, 'combinatory' urbanism as a vehement rejection of standardised architecture and the separation of city functions in the urban zoning of the older mode of functionalist modernism.

"It combines apartments, offices and commercial zones in an intense medium-rise urbanism and remains one of the most radical architectural achievements of the 20th Century."

Les Damiers by Michel Folliasson, Jacques Binoux, Abro and Henri Kandjian (1976)

"This was a very ambitious housing project of its time that involved the clearance of old housing stock in the working-class area of Courbevoie, creating generous apartments and commercial zones in a stepped arrangement of terracing.

"Despite its own monumentality, it is now dwarfed by the commercial and financial tower blocks of La Defense, and currently undergoing a slow process of decanting and demolition.

"Its demise is largely a result of inflated land values in this area of Paris. What is also being erased here is a distinct period environment of public art of the decorated facade and public furniture."

Cité Rateau by Jean Renaudie and Atelier Renaudie (1984)

"This is a remarkable housing development in north Paris, but an example of a brutalist architecture that has endured very poor practices of maintenance and alteration. It was designed by Jean Renaudie and realised by Atelier Renaudie, which was established by his son, Serge, after Jean's death in 1981.

"It possessed a remarkable ground plane of complex circulatory and public spaces, but a planned integration of work and living spaces was never completed by the commissioning client.

"These images are from 2018, but in returning to the project in 2022, we discovered Cité Rateau transformed by an obtrusive regime of gated access, which now prevents the porosity of circulation from the street previously enjoyed and destroys the basis of its radical, communal, spatial philosophy."

The photography is by Nigel Green.