Cristóbal Palma photographs ill-famed Buenos Aires slum before redevelopment

As works began to transform the notorious Villa 31 slum into an official Buenos Aires "barrio", Chilean photographer Cristóbal Palma documented its distinct architecture.

Villa 31 is the most well-known "villa miseria" in the Argentinian capital, home to more than 40,000 people including both Argentinian nationals and immigrants from neighbouring countries.

Palma started visiting in 2019 when work was already underway to integrate the neighbourhood into the infrastructure of the city, with sewage systems, running water and connection to the power grid.

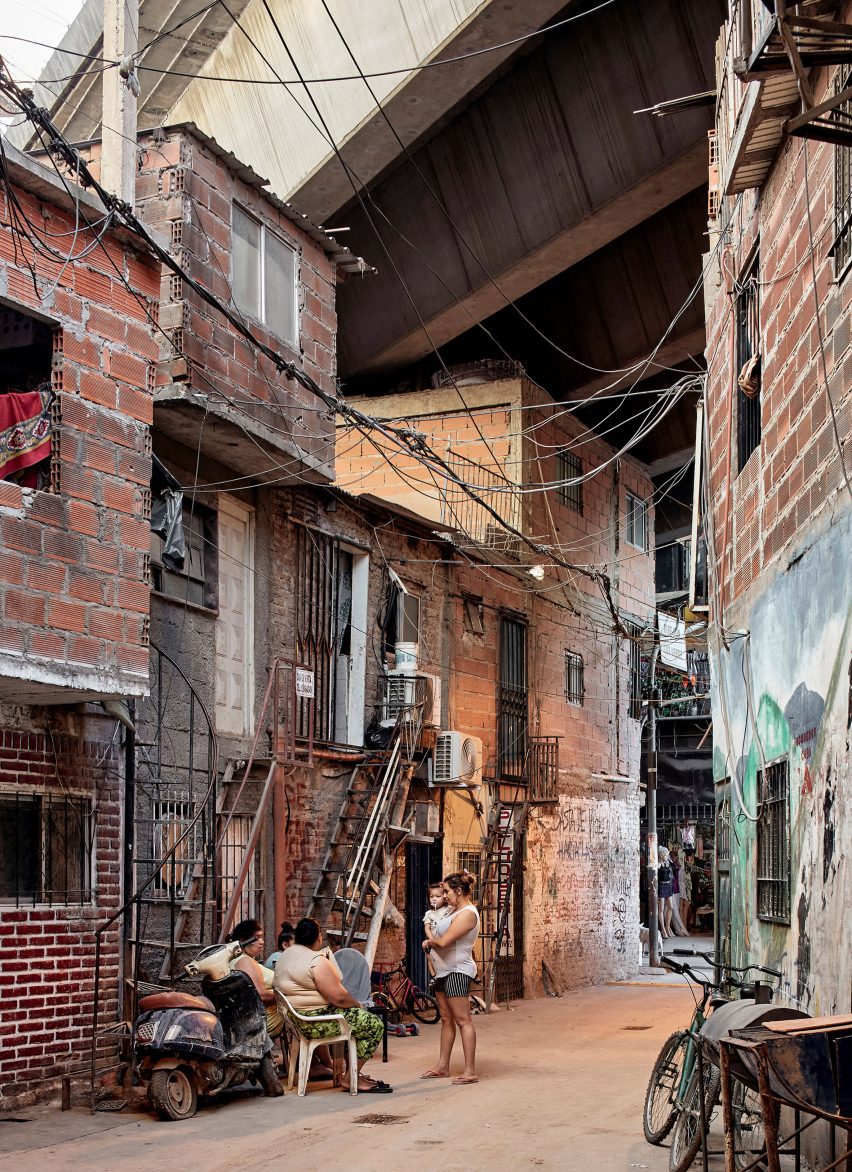

His photographs reveal the ad-hoc buildings and dense streetscapes that defined this unplanned part of the city.

"It was unique from other kinds of favelas because the pressure on land was so great," Palma told Dezeen.

"It had a funny kind of metropolitan feel because it was so dense, with up to six or seven storeys of construction. I got the sense that, although it was very poor, there was a lot of pressure to have land there."

Villa 31 has a definitive border, bounded by a highway on one side and a railway line and station on the other.

This fuelled its isolation, despite a location close to the city centre and adjacent to the affluent Recoleta neighbourhood. Since the 1930s, it had developed without any centralised planning or regulation.

As a result, the resident-built homes were built along narrow, unpaved streets. Cables hung overhead, illegally drawing electricity from nearby power lines, while rain caused the streets to fill up with polluted water.

"Some of the structures felt very precarious," Palma said. "It felt like they were about to collapse."

"But it was also a kind of paradigm of what a city could be if there were no cars," he added.

"The way people interacted with public spaces felt, in a way, very sophisticated."

In 2016, the city government started drawing up plans to redevelop Villa 31 and improve conditions for its residents.

The project was not welcomed by all; media coverage revealed that many residents were fearful of the changes, with concerns they would be forced to leave their homes without any eventual benefit.

"It's very politically charged," said Palma, "because so many different people have tried to do different things there over the years".

The scheme, funded by the city government, the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank, has already transformed the newly renamed Barrio 31, with more changes still to come.

As well as paved roads, sewage and power, the neighbourhood now has three schools and a bank, and is served by buses for the first time. Residents can also get mortgages to buy their homes.

Palma felt it was important to create a record of how things were before redevelopment began, offering insight into what life was like for the residents of this neighbourhood.

"In Latin America, these kinds of favelas are usually on the periphery; you don't get to see them unless you go there. But this one was so very present," he said.

His photos show buildings rising up around the highway flyover, made from an assortment of different materials, while others show rooftops covered with materials, washing lines, water tanks and paddling pools.

He also captured portraits of some residents within their homes.

"From the outside, it looked very homogeneous," he said. "But once I went in, I noticed all of these different sub-neighbourhoods, some more affluent and some more precarious."

"It was so dramatic with the highway going through," he continued. "Some people could actually touch the highway from their bedrooms."

Another thing the photographer observed was the lack of nature within the neighbourhood, besides the occasional tree. "It was a big contrast with the rest of the city," he said.

Palma is one of the judges of this year's Dezeen Awards. He has run his own photography studio, Estudio Palma, since 2008 and is one of the leading architectural photographers in Latin America.

He is currently showing four large-scale prints from the Villa 31 series in an exhibition at Galería Gallo, which is part of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile in Santiago.

The exhibition Construcción Villa 31 is on show at Galería Gallo from 10 August to 4 October. See Dezeen Events Guide for more architecture and design events around the world.