"Social responsibility has been forgotten" - author of book on Ulm School of Design

News: social responsibility has fallen down the agenda of today's designers and design schools, according to the author of a new history of Ulm School of Design, the German institution that reshaped design education in the 1950s and 1960s.

"Social responsibility is more important than ever. In recent years this has been forgotten," Dr René Spitz told Dezeen. "Since the 1990s, design [has] largely concentrated on the formal aesthetic finish: elegant, eccentric, unusual, luxurious. We have failed to formulate new answers to the question of what societal responsibility is today – specifically, beyond phrases and slogans."

In his new book, HfG IUP IFG Ulm 1968-2008, the Cologne-based writer, academic and design consultant considers the impact the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm (HfG) has had since its closure in 1968 after just 15 years in operation.

"Ulm was unique", says Spitz. "There was no other school of design which was fed from a similar socio-political impulse."

Following in the footsteps of the Arts and Crafts movement and the Bauhaus before it, Ulm taught students to question the designer's place in society.

"The special quality of Ulm was to focus on this question and to combine it with a humane, holistic approach and scientific methods," he explains. "Nowhere else was the theoretical deliberation and practical experiment so concentrated on the question of the designer’s social responsibility."

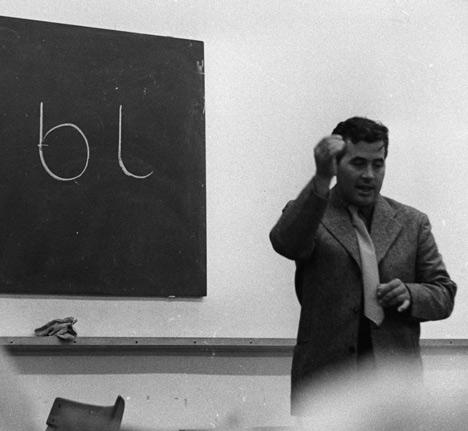

Above: Otl Aicher, one of the founders of Ulm School of Design, pictured in 1954

The school's answer was to encourage an approach to design that would help build an open-minded and democratic society – an especially pertinent ambition in post-war Germany.

"That's why they didn't care about the design of luxury products, like an exclusive coffee set. They developed durable goods," such as stackable tableware for youth hostels and concepts for practical family cars, explains Spitz.

HfG was also known for its collaboration with Braun in the 1950s, which saw the newly-hired designer Dieter Rams working with teachers and students to develop the functional and economical style that became the German consumer products company's trademark.

Despite its brief lifespan, the school's influence continued through its subsequent iterations as the Institut für Umweltplanung (IUP), which existed until 1972 to serve existing students, and, since 1988, the Internationales Forum für Gestaltung (IFG), the platform from which the HfG Foundation now operates.

Spitz became interested in the history of the school in the 1990s when he worked alongside Otl Aicher, one of Ulm’s founders along with Inge Scholl and Max Bill, and between 2004 and 2007 he was chairman of the advisory board of the IFG.

Today's designers still have much to learn from the legacy of Ulm, concludes Spitz, explaining that researching a design problem thoroughly and placing it in context is vital.

"This sounds simple, but it's hard because you need a lot of time if you really want to understand a complex situation," he says. "We must get deep below the surface. Otherwise we keep on producing problems."

Dezeen has been reporting on the changing face of design education in recent weeks, following a warning that the Royal College of Art will become a "Chinese finishing school" if the UK government doesn't do more to encourage young people towards art and design, while graphic designer Neville Brody, who's dean of communication at the RCA, has slammed politicians for removing creative subjects from the curriculum.

Photographs are courtesy of Dr René Spitz.