"The idea is that the phone disappears"

Smart glasses, wearable computers and skin-mounted sensors will soon guide people through airports and shops and allow them to pay for goods and services, according to John Hanke, the head of Google Maps (+ interview).

"I think the general idea is that the phone as an object kind of disappears," said Hanke. "People are working on skin sensors and other ways of transmitting information to us in a way that's passive and that doesn't require us to divert our attention in the way that we do with the phone today."

In an interview with Dezeen to mark the UK launch of Field Trip, Google's new location-based publishing app, Hanke said: "When people pull out their phones and begin interacting with an application they're basically pulling themselves into this bubble and putting up a wall between themselves and the real world around them. So it can take on this negative, anti-social aspect whenever you're using smartphones and the internet."

Hanke, who invented Google Earth and runs Google's NianticLabs division, added: "We can use information technologies to enhance your experience with the real world without taking you out of the real world."

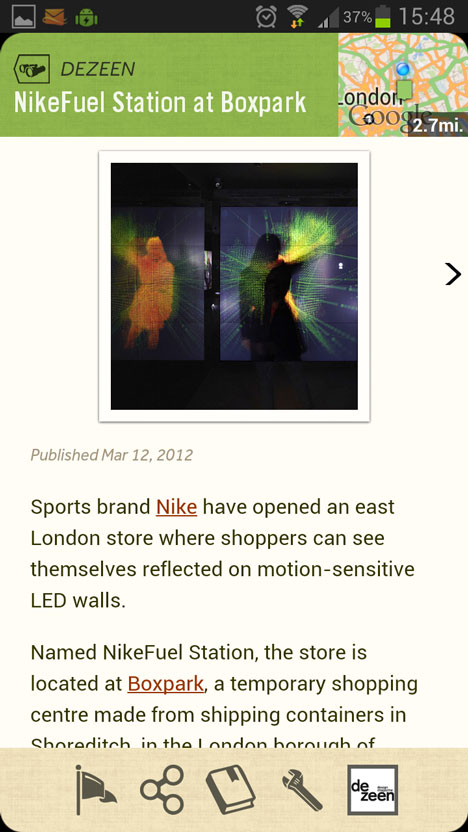

Field Trip works out where you are and provides information about your location from a variety of websites, including Dezeen. Users browse text and images about nearby buildings, shops and services. Field Trip launched in the USA this autumn and will be rolled out to other countries next year.

Hanke predicted that location-based technology will soon allow people to navigate within buildings and make purchases. "Google has been working on this indoor location-mapping technology that allows you to get high-fidelity, high-accuracy location inside," he said. "So that you can, for example, find your gate in an airport, or to find a specific aisle in a store, or to find a specific exhibit within a museum."

Earlier this year Google unveiled Google Glass (top image), a concept for spectacles that display data. These could eventually allow users to find and pay for services such as cycle and car hire: "In the future the whole transaction could happen through Google Glass, payment and everything."

Read more about Field Trip in our earlier story and see all our stories about Google.

Here is a transcript of the interview between Hanke (above) and Dezeen editor-in-chief Marcus Fairs:

John Hanke: I'm John Hanke. I run a group called NianticLabs at Google, which is kind of a start-up exploring mapping and mobile technologies. For about six years before that I was the vice-president of product, in charge of Google Maps, Google Earth and Google Local.

Marcus Fairs: When did you join Google?

John Hanke: I was a CEO of a company called Keyhole that created the original Google Earth technology. We were acquired by Google in 2004. We came in and then relaunched our product as Google Earth.

Marcus Fairs: Tell us a little about that. How did it come about?

John Hanke: We started working on that around 2000. A lot of people had this vision of a map that would be this virtual globe that would have satellite imagery and would have these information layers available. We were inspired by science fiction. There's an author named Neal Stephenson who had described a product like that in a book he wrote called Snow Crash. So there was this archetype, and it was just time for it to happen. The technology has finally made it possible to do it, so we wanted to see if we could make it real.

Marcus Fairs: There’s a very long history of maps, from people scratching lines on bits of bark through to the early maps of the world, but what difference did it make to people's lives when they could zoom in on any point in the whole world? How did that change the way people thought about their lives and the planet they live on, as well as how they were going to get the next place?

John Hanke: I guess I would leave it to other people to draw the grand conclusions about what kind of an impact it's made on the world. But I think it has to be a positive experience for people to be able to browse around the world and when you look at a country, to be able to zoom in and see that it looks a lot like the place that you live.

You know, when you explore China you're not zooming into a big red polygon, you're seeing houses and cities and a landscape that you can relate to. I mean, I think there has to be an underlying positive impact on the world for people to have that experience or exploring and seeing similarities.

Marcus Fairs: And in terms of that kind of technology, how detailed can it get? Can it get to the point where you can zoom in and figure out if your friends are in the cafe already? How much real-time data can that kind of technology provide?

John Hanke: Well as you probably know, Google is now doing indoor mapping and indoor Street View so that you can go from space to a city to the street to the inside of a cafe or restaurant and experience what it's like inside. And you have all of these kind of real-time technologies for knowing about what's going on, where your friends are, so I think we're getting closer to that idea that you can know what's happening at any place on the world at any time. It's not fully realised yet, but we're getting there.

Marcus Fairs: A problem with digital maps, apps and social media is that if you're looking at your phone you're not looking at where you are. You're not concentrating on your route and you're not enjoying the city, your friends, your family.

John Hanke: Yes and that’s the area that my new group is working on. Some people call this augmented reality, some people talk about ubiquitous computing, but the gist of the idea is that we can use information technologies to enhance your experience with the real world without taking you out of the real world.

People have written about this problem of the information bubble. When people pull out their phones and begin interacting with an application they're basically pulling themselves into this bubble and putting up a wall between themselves and the real world around them. So it can take on this negative, anti-social aspect whenever you're using smartphones and the internet.

So we would like to explore this frontier of providing information that enriches your life and your experience of the real world, but does it seamlessly by working in the background and by sequencing that information automatically.

So we launched this application called Field Trip in the US about a month ago that does that. It looks in the background for interesting things around you. We work with publisher partners who make their feeds available within that product and it tells you about cool stuff that's nearby without you having to pull out your phone and press buttons on a UI. It all happens in the background.

Marcus Fairs: Why did you invite Dezeen on board?

John Hanke: Well I'm a huge fan of Dezeen and its great coverage of global design community, and we're delighted to be working with you.

Marcus Fairs: How will our content be useful to someone who’s interested in architecture or design?

John Hanke: The notion is that I can take a stroll through the streets of London and the application will automatically surface a card. Or if I had a headset connected it can actually read that information to me. If I'm walking by a place that Dezeen has written about - it might be a piece of architecture or it might be a really cool local shop, it might be a great coffee shop, or some other piece of design - it will tell me about that without me having to constantly be doing searches or interrogating an app.

Marcus Fairs: How precise is the mapping technology? Could you use it to navigate around a room or does it only really work on the scale of a block or a street?

John Hanke: For what we're doing with Field Trip right now the accuracy is tens of metres, so it’s really designed for use outdoors. We would love to have it work indoors. The location technology is really just now getting good enough to do that. The problem historically has been that GPS doesn't penetrate indoors, so you don't get that very high quality precision location inside of a building. You have to fall back to something like wifi-based location when you're indoors, which tends not to be accurate.

But Google has been working on this indoor location-mapping technology that allows you to get high-fidelity, high-accuracy location inside, so that you can, for example, find your gate in an airport, or to find a specific aisle in a store, or to find a specific exhibit within a museum.

We have to do additional work to go out and map those locations to get that high-precision indoor mapping, and we're just starting to do that.

Marcus Fairs: Will people be able to find stories from Dezeen’s archive? At the moment people tend to consume the latest stories on the site, but we've got years of archived stuff about buildings around the world.

John Hanke: Yeah that's the reason I'm really excited about it. These stories that have been written over the years may not be viewed as much. But when you're out moving through the world, when one of those stories is about a place that's near you, it's incredibly useful and relevant. So we want to help people discover that.

Marcus Fairs: How will Field Trip work? You download the app and tell it what they're particularly interested in, and then the information just pops up as you navigate the city?

John Hanke: Yes. You configure Field Trip before you start the application for the first time and select the feeds that you want. There are different categories that you can select from. Then as you move around through the physical world, information from those publishers about something that is nearby automatically pops up on your phone.

Marcus Fairs: And does it work around the whole world?

John Hanke: It works around the whole world, but so far we've only released the application for the United States. We're waiting in each country until we have sufficient coverage with partners before we officially launch it. The next one up for us will be the UK.

Marcus Fairs: How else can location-based services change the way we interact with real places?

John Hanke: That's a big question. There's a wealth of information available on the internet that makes our lives better but whenever we're out, moving around through the real world, even though that information is there and theoretically accessible, it's actually so tedious and time-consuming and awkward to go and retrieve that information or use those services, that we don't. So effectively, we're not really getting the full benefit of what's already available on the web when we're out moving about in the physical world.

So if we could figure out better user interfaces, where you have agents that work in the background that surface this information to us automatically, I think we can see enhancements in many areas.

Marcus Fairs: How will this information be consumed? Will we have heads-up displays on the inside of our sunglasses?

John Hanke: I think the general idea is that the phone as an object kind of disappears. People talk about wearable computing: we might have audio devices; we might have something like Google Glass. People are working on skin sensors and other ways of transmitting information to us in a way that's passive and that doesn't require us to divert our attention in the way that we do with the phone today.

Marcus Fairs: How do skin sensors work?

John Hanke: Researchers are working with things that are fixed to the skin; and sensations can be transmitted that way. That's one of the more far out types of technologies. Things like the Google Glass can paint information into your field of view about what's around you, but the idea is that all of these are a way of getting information to you that allows you to remain in the context of what you're doing without interrupting that.

Marcus Fairs: So the phone is really a transitory bit of technology. It's sort of between the computer and something that's part of your clothing or your skin even?

John Hanke: I think that's true, yes. I think the phone as the single way that you're benefitting from information technology probably will evolve into something that looks a lot different from that and isn't the singular artifact that you obsess over and spend all your time interacting with. I think the idea is that it sort of fades into the background and that these other mechanisms are providing the information to you.

Marcus Fairs: So you're passively receiving information about what's around you, but how can technology help you interact with the city?

John Hanke: There's no reason why many of the things that we interact with today can't have a digital interface to them. So a building or a commercial service can benefit from having a digital UI that's telling you about it and allowing you to make a transition or allowing you to interact with it.

Marcus Fairs: Can you give an example of something like that?

John Hanke: Well anything that has a physical UI today may be much more useful and enriched with a digital one. Bike sharing would be one example. How much richer could the act of renting a bike be if it was happening through this digital interface and was projecting into something like Google Glass? I could see the bikes, I could see the road network, I could understand availability across the city. In the future the whole transaction could happen through Google Glass, payment and everything. Just imagine a digital interface to the world around you.