"Architecture has run out of excuses when it comes to explaining a lack of gender parity"

Dezeen's latest survey shows that the number of women in architecture leadership roles has doubled, but the industry needs to work harder to attract and retain women in senior positions, says Christine Murray.

The improvement in the number of women in senior leadership roles in the past five years revealed by Dezeen’s survey of top 100 global architecture firms is a surprise win, with the proportion of women in the highest-ranking jobs having doubled from ten to twenty percent.

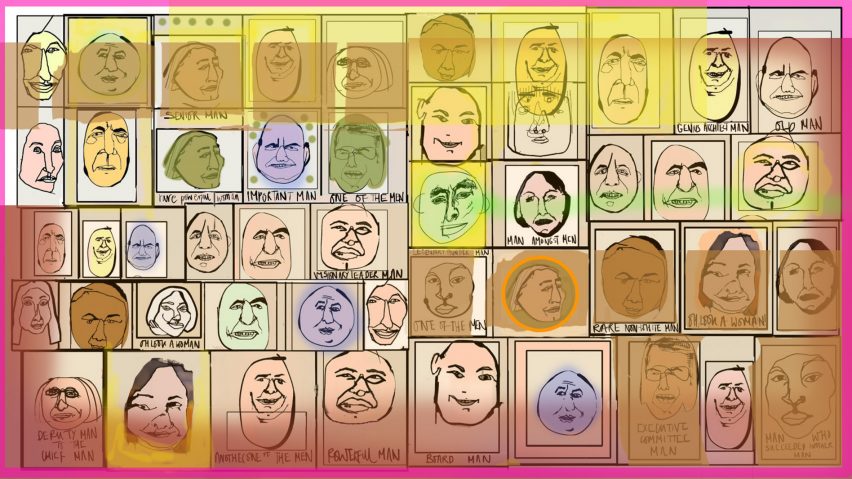

The rate of growth suggests some firms are actively tackling the lack of female designers at the top. Dezeen’s survey, although a bit crude in its methods (counting headshots on websites) will add welcome heat to simmering concerns that an all-male leadership team is a business and PR liability.

Fifty-two per cent of the practices in the global top 100 boast exactly zero women at the top table

But let’s not get carried away. It’s still just 20 per cent, and most of the top 100 global firms in architecture and design still have no women in senior leadership at all. An incredible 52 per cent of the practices in the global top 100 boast exactly zero women at the top table. Almost half (45 per cent) of the firms have failed to improve the number of women in senior leadership in the past five years. And nearly a fifth (17 per cent) of practices have no women in their second tier of management.

Architecture has run out of excuses when it comes to explaining a lack of gender parity. In the US, two out of five new architects are women, according to the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB). In the UK, the gender split of architects under 30 is exactly 50/50, according to the Architects Registration Board (ARB) annual report 2020.

Is it just a matter of time before these women ascend to senior management? Maybe. But in 2002, the Royal Institute for British Architects proudly reported that architecture students were 38 per cent female. Twenty years later, where are these women now?

Thinking positively, Dezeen’s research does show an increasing number of senior positions for women at the highest levels of the profession. So what can design firms do to attract and retain women in management? A closer look at the more balanced firms in the league table suggests changes to benefits, pay and workplace culture for a start.

Taking 50:50 as the sweet spot, twelve firms have a proportion of women between 44 and 67 per cent at senior leadership level. It’s no surprise to find three of these are headquartered in Scandinavia: CF Moller, White Arkitekter and Link Arkitekter. There are also three in the USA: CannonDesign; DLR Group and Gensler, with one a piece in Bahrain (KEO), Hong Kong (Leigh & Orange), India (Morphogenisis), the UK (Purcell), China (Capol) and France (Wilmotte).

Gender parity can happen anywhere

The global spread shows that gender parity can happen anywhere. However, the disproportionate representation of Scandinavian countries in the top 12 points to a systemic gap that practices need to breach: the financing of care. Nordic countries have subsidised childcare, generous parental leave and eldercare.

"Globally, women do 75 per cent of unpaid care work," says Alice Brownfield, an architect at Peter Barber Architects and co-founder of Part W action group for gender equality. "This is exacerbated by the gender pay gap and the lack of work opportunities that fit around life’s other demands."

In short, if the welfare state doesn't enable high-quality, flexible and affordable social care, your architecture practice will have to make up that difference in salary or perks, plus a working culture that doesn’t penalise employees with kids, parents or other caring responsibilities.

"A work culture that assumes long hours, late nights, and complete focus on a project is more likely to put women in a position of having to choose between family and work, or having one or both suffer," says Leslie Kern, author of Feminist City and director of women’s and gender studies at Mount Allison University.

For example, some architecture practices host design crits with their top brass weekly on Friday nights at 6pm, forcing employees to cede what should be family or social time. While women suffer disproportionately in these work/family clashes, they are just canaries in a creative-industry coalmine.

Work and life becomes intertwined in a way that makes creative workers likely to self-exploit

In the architecture studio, a love of design and the collegiate atmosphere is supposed to supersede the need for a living wage and a social life – and for many women it does, until other responsibilities get in the way. Long hours and intense collaboration on projects turn bosses and co-workers into friends and family. Work and life becomes intertwined in a way that makes creative workers likely to self-exploit, and easier to manipulate into working extra hours for no pay.

Because all work is collaborative, it’s hard to argue the merit of an individual contribution: the creative fruits are the work of so many hands, the value of each individual worker is considered marginal, even non-existent.

In his paper on the neoliberal creative economy, Ashley Lee Wong writes: "Through promotion of lifestyle, recognition and fame, the creative industries makes jobs desirable and at the very same time creates the conditions for self-exploitation and exploitation by employers. We may love the work, but we hate the stress and lack of financial security. It is difficult to find stability in a highly competitive environment where one constantly has to promote oneself in order to secure the next job."

As a cog in the property industry, architecture is just one part of an expensive machine that extracts value from land, under pressure to make the largest possible return. Depressed wages and exploitation of creative workers are part of the economic model. Women are squeezed out of top management where the working culture, or lack of state support and employee benefits, mean they can’t afford to play. Firms that do not address this will be forced to choose from a less-talented pool of the privileged who can.

The visibility of women at the top is important

As Kern says, "A cooperative culture where all contributions are valued is more likely to retain women and others who typically either lose in the male-dominated competitive world or opt out of this kind of culture."

The visibility of women at the top is important. Seeing women in management positions might encourage others to stay. But this can also lead to added pressure on women to be role models, activists or counsellors in addition to their day job. I’ve heard of women architects being asked to write their company’s maternity policy or start mentorship programmes, despite having zero experience in these areas and an already challenging workload.

After I was appointed editor of the Architects’ Journal halfway through maternity leave with my first child, I was asked what I would do to improve the status of women in architecture. I was also expected to serve as a "role model" for future mothers in the media company. Would a male editor have faced these pressures, or been expected to do any job other than that of editor?

"Relying on senior women to do unpaid work as mentors, equity consultants, and policy makers increases their workload and likely pulls them away from the kind of projects that get recognition and compensation," says Kern. "This could contribute to burnout, frustration, and a desire to leave the field."

This year’s top 100 list proves that alternative approaches are available and that change is possible. With public bodies and private capital increasingly looking to hire design firms with ethics and values, if only for selfish reasons, practices should improve gender parity in the senior ranks.

Dezeen’s count of the numbers reveals strong growth on feeble progress. To retain these women and add to their ranks, the design studio culture must change. Practices should seek to adopt a working culture in which there is more to life than architecture. You can love design and work hard, but architecture should not, like an abusive boyfriend, demand to be your everything.

Christine Murray is the founding director and editor-in-chief of The Developer and The Festival of Place. She was formerly editor-in-chief of the Architects’ Journal and The Architectural Review, where she founded the Women in Architecture Awards, now known as the W Awards.