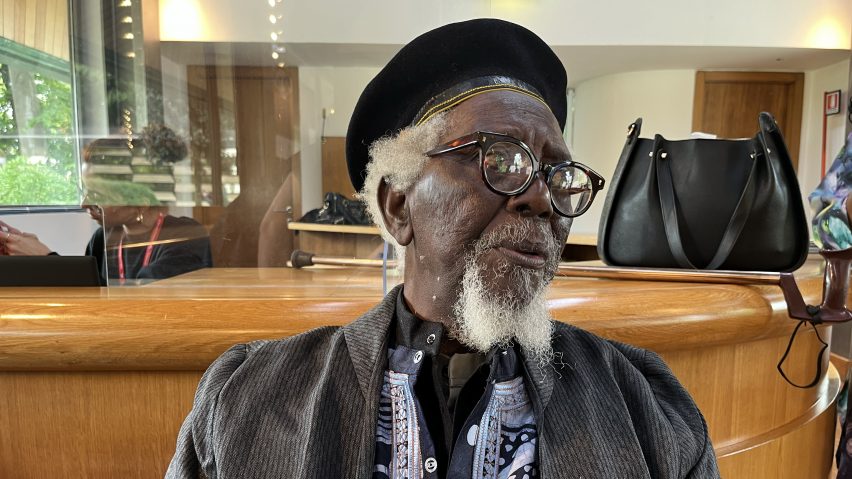

"Nothing has been built yet in Africa" says Venice Golden Lion-winner Demas Nwoko

Nigerian architect Demas Nwoko calls for the creation of an African school of architecture and criticises Europe's influence on the continent's built environment in this exclusive interview.

Speaking ahead of being awarded the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale, Nwoko said that the next generation of African architects must take responsibility for building the future of the continent.

"We have to bring our own future generations to take up the task," Nwoko told Dezeen during the biennale.

"When they agree to take it up, they can then open dialogue with people from the other side [the West], who, by the way, are still ahead – especially in material production."

"Africa is still the fresh, future frontier"

He believes that there is a lineage of African architecture that was negatively interrupted by colonialism and there is now an opportunity for African architects to design buildings which are "suitable and affordable" for their local contexts.

"Africa is still the fresh, future frontier," said Nwoko. "Nothing has been built yet. All this time the white man in Africa has been undoing what our fathers had done."

"I don't see any positive attribute to the architecture that Europe brought to Africa," he continued. "Somebody can correct me, but I live there. I know the buildings. I know that the people don't live in them."

Nwoko's vision for the future chimes with the wider themes of the biennale, curated by Scottish-Ghanaian architect Lesley Lokko who is steering the festival with the guiding idea of Africa as "the Laboratory of the Future".

At the time of Nwoko's award announcement, Lokko said "with all of [the biennale's] emphasis on the future, however, it seems entirely fitting that the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement 2023 should be awarded to someone whose material works span the past 70 years, but whose immaterial legacy – approach, ideas, ethos – is still in the process of being evaluated, understood and celebrated."

"Fifty years ago the profession of architecture had failed already"

Born in 1935 in the southern Nigerian town of Idumuje-Ugboko, Nwoko's built projects include the Dominican Mission Chapel and the Cultural Centre in Ibadan, and the Benin Theatre.

He decided to go into building and development to match what had been achieved in Europe. Along with being critical of Europe's influence on Africa he also has his frustrations with the way the European schools have stunted or shaped architectural education in Africa.

When asked who gets to be an architect today he took the opportunity to reflect on the trajectory of the profession and how a brighter future can be achieved for his homeland.

"Unfortunately it's the same as it was fifty years ago," he said. "Fifty years ago the profession of architecture had failed already. We, who were entering it at that time, have been fighting a battle that looks like a lost battle because nothing has come off right."

Nwoko thinks "the practice of architecture almost died at its beginning" and that "from the day that the profession coined the name [architect] it has never done as well as when it was a guild of builders". He sees the role of the architect primarily as that of a builder.

"Our contact with the West has been our undoing"

Explaining how academia has removed the profession from this primary role, he said "when architecture moved into the school, into the polytechnic, it started to decline – and that's the evil of formal school, because it's not a creative place".

"Architecture school is a place of review," he continued. "Not creative. Not preview and not looking to the future. In school they only take things that exist and put it together, to be written down and documented in books. Once you are doing that everything is fossilised".

"I said I would rather practice at home and you, in Europe, can come and see – just as I have come and seen what you have done, you can come and see what I have done," he explained.

"Our contact with the West has been our undoing," he continued. "They might not have been doing it purposefully to rubbish us – they thought that what they had was the best for everybody. And they wanted to create a space to bring in what they had – fair enough."

"But it would be too much to think that the people who brought us to this impoverished state are the ones who are going to volunteer to repair it," he added.

Nwoko's criticism of the current architectural context in Africa is leavened by an inspiring vision of the future and a call for the next generations of African architects to design the built environment for the people who live there.

Nwoko identified Burkinabé architect and Pritzer Architecture Prize-winning Diébédo Francis Kéré and Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye as practitioners who are helping to build Africa for Africans.

Both were featured in the Force Majeure exhibition in Venice, which shines a light on 16 African and diasporic designers.

Adjaye, who was also in Venice with a pavilion project said at the unveiling of his model and plans for The Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in Delhi that with his work he has "moved back to Africa".

"That's really important to me," he continued. "In a way, I still feel like Africa is emerging and finding its own voice and identity."

"Once we have built a generation that will stay, we can affect change"

Nwoko recognised the necessity of the globally collaborative way that someone like Adjaye works.

Despite his earlier comments about the evil of formal school, Nwoko thinks part of the strategic future for the continent is the creation of a new architecture school.

"Specifically, a school that will make it possible [for the next generaion] to take over the responsibilities [to build Africa's future]. Because if they don't, then our impoverishment in matters of the built environment will [continue]".

"Once we have built a generation that will stay – and not migrate to Europe, for education or to live – we can affect change."

Other recent Dezeen interviews with architects include conversations with this year's Serpentine Pavilion architect Lina Ghotmeh, Pritzker Architecture Prize-winner Shigeru Ban and British architect Norman Foster.

Dezeen in Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.