Every recognisable object is a "political work" says Ai Weiwei

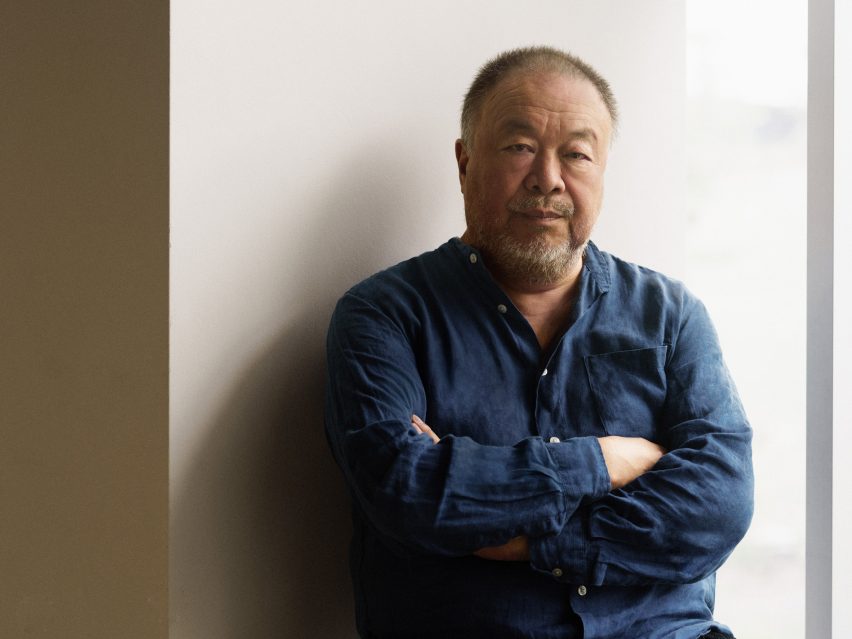

Multidisciplinary Chinese artist Ai Weiwei tells Dezeen why he thinks all objects have political significance in this exclusive interview.

Known worldwide for his use of art as a tool for activism, Ai has created decades' worth of projects spanning a range of media – from architecture and film to installations and performance art.

The artist recently presented his first design-focused exhibition, called Making Sense, at London's Design Museum. It featured vast collections of thousands of found objects, ranging from Stone Age weapons to crowd-sourced Lego bricks.

"Even daring to name anything is political"

"Every object, if it can be recognised or has a name or a definition, is a political work," Ai told Dezeen at the museum. "Because of our judgment about values, even daring to name anything is a political act."

The political energy of the object comes from the user or observer, who will respond to it differently based on their own lived experience, Ai explained.

"We see things differently," he said. "Someone from London may see something in a different way to someone from Africa or from Asia."

"We are products of given conditions – our practice, our ability, even our knowledge or definition of ourselves. And so it's really the reaction of a given condition."

Born in Beijing in 1957, Ai has created work with a consistent political angle throughout his career. In particular, the artist is openly critical of the Chinese government. He has often expressed his belief that the country's architecture is stagnating under its Chinese Communist Party leadership.

While Ai collaborated with architecture studio Herzog & de Meuron to create the National Stadium – the main arena for the 2008 Beijing Olympics – he later distanced himself from the project in direct protest against the Chinese state.

Among Ai's artworks that challenge his native country's government is Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn – a 1995 black-and-white photography series that shows the artist dropping and smashing a Han Dynasty-era urn, which was around 2,000 years old at the time. The project aims to criticise the destruction of countless antiques during China's Cultural Revolution that began in 1966.

Despite this political focus, Ai said that he is cautious about pigeonholing his own artwork – or anything else – into distinct categories, including art or design.

"The problem with categorising is [it is] trying to take a shortcut. When people like to use fixed ideas, those concepts become emptier and emptier. It is truly a problem."

He argued that categorising things in this way "is an issue of education first", particularly citing the limitations that can arise from a lack of multidisciplinary learning at institutions such as schools and universities.

"You're trying to quickly tell people that [only] certain vocabularies are safe to use. But very often you see people use empty words. Because [these terms don't] really relate to emotions, consciousness or self-interpretation under judgment," reflected Ai.

"So we are living in a fast food, plastic or AI [artificial intelligence] world," he added. "We become handicapped."

"We still know very little about humanity"

The artist highlights the plights of various marginalised people in his projects, having previously installed three cage-like structures in New York City in protest against then-president Donald Trump's strict border-control measures, and created a wall of 2,000 life jackets in Québec that were worn by Syrian refugees attempting to cross the Mediterranean Sea.

"Human environments are never really fully developed or protected," he said. "Most of the time [they are] ruined by education, even with all the good intentions."

"We still know very little about humanity," added the artist.

Ai expressed his interest in the process of creating artwork, rather than solely appreciating the physical end result.

"A process itself is to recognise yourself and to make judgments about your approach," he explained.

Considering the value of creativity, Ai argued that "we are all born with the same ability" to create art, but that "art can never really be taught but can only be untaught" by our education systems.

"To do art is very different to becoming an artist because artists as professionals are selling works to support themselves. And very often, they're all bad," he said.

"And of course, when they [the artists] become sophisticated that's when they have to find a new language to illustrate the complexity of their thinking. But the ones who call themselves artists very often relate to public assumptions. So, it's not so pure, it's very much informed by the market."

Despite this, Ai confirmed his faith in the communal benefits of using art as a form of self-expression.

"I think it's part of humanity. If anybody does not really care about that, I think that is probably the biggest waste."

The images are courtesy of the Design Museum unless otherwise stated.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.