Atomik is vodka brewed from grain grown in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

Scientists have created Atomik, a brand of artisan vodka made from rye grown on land in Ukraine abandoned since the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, to help the people living there.

The first ever bottle of Atomik vodka has been triple distilled then diluted to 40 per cent using uncontaminated groundwater drawn from an aquifer in the town of Chernobyl, 10 kilometres south of the defunct Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant.

By making the vodka, the researchers aim to show that alcohol made from crops grown near the site is safe to consume, and provide a means of income for local producers.

After rigorous testing, no radiative isotopes such as plutonium, americium, cesium or strontium show up in the finished product.

Only a trace of carbon-14 can be found in the first bottle of Atomik, a level that is found naturally in alcohol.

The Chernobyl Spirit Company was set up by a team of scientists from Ukraine and Portsmouth University in the UK, who worked with people living in the zone to monitor and test the farming process and the results of the vodka-making.

They wrote a report to demonstrate that alcohol made from crops grown in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (CEZ) and the Zone of Obligatory Resettlement is safe, with the single bottle of Atomik as the physical proof.

"From a radiological point of view it is safe to drink," said Jim Smith, who co-authored the report and helped found the Chernobyl Spirit Company.

"I think this is the most important bottle of spirits in the world," he added. "It could help the economic recovery of communities living in and around the abandoned areas."

The scientists hope that once the vodka is accepted as safe it can go into full production, with 75 per cent of the profits from sales going to local communities and wildlife conservation efforts within the exclusion zone.

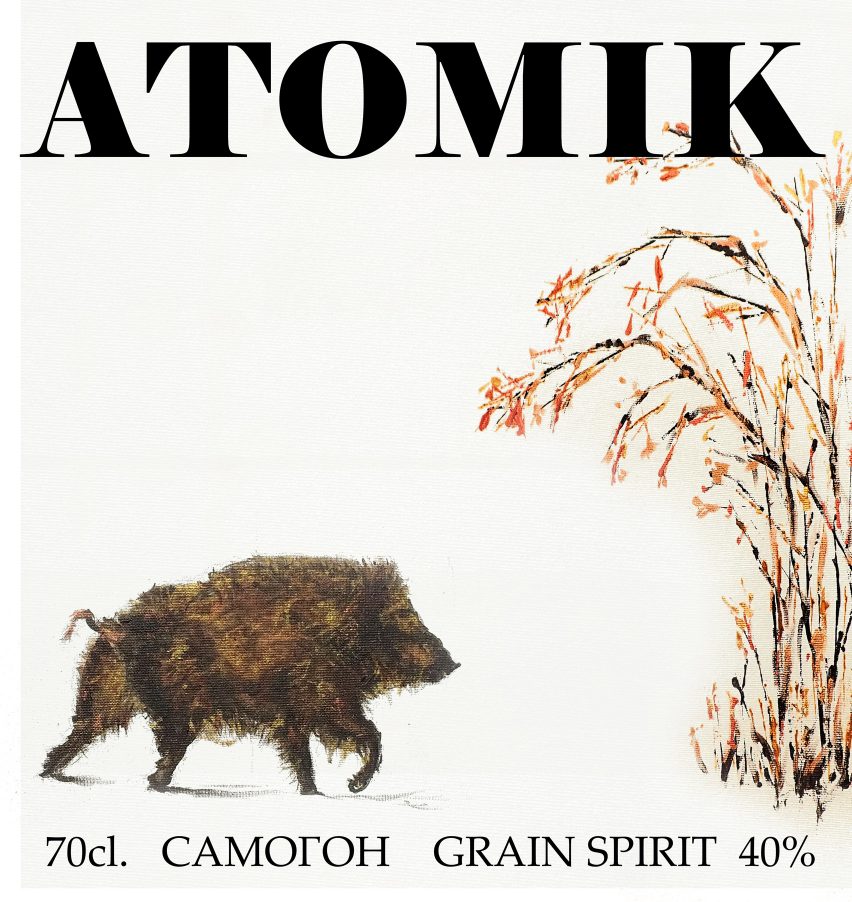

Atomik's glass bottle is decorated with a picture of a wild boar, one of the species that has benefited from the reduction in human activity after the disaster.

"The wild boar represents the resilience of nature, but also the long and difficult road to recovery of the Chernobyl-affected people in the face of too many simplistic and often wrong assumptions about their environment," said the makers of Atomik.

Over 6,000 kilometres of land in Ukraine and Belarus has been un-farmable since the No. Four nuclear reactor at the Chernobyl power plant exploded in 1986, causing an open-core reactor fire and launching radioactive contamination into the air.

Although officially abandoned, many people still live in the area and are suffering from high levels of unemployment.

Contamination from nuclear disasters can introduce artificial radionuclides – atoms with excess nuclear energy – into the food chain.

While these can be found naturally in most foods, in high concentrations they could be dangerous, and even if levels are safe people are reluctant to buy anything that might be seen as contaminated.

The scientists' report proves that crops grown in the exclusion zones are either already safe or at levels of radioactivity that can be removed by Atomik's triple-distilling process.

With their report and the vodka production they hope to prove that radiation levels in the inhabited parts of the zones are now at a normal level and help reduce the stigma for people living and working there.

A 2006 report from the World Health Organisation concluded that poverty and mental health issues resulting from the legacy of the disaster pose a far greater threat to local populations than any residual radiation.

Some of the people displaced by the disaster ended up living in the UK, where Spheron Architects built a memorial chapel for victims of Chernobyl.

Video and photography courtesy of the University of Portsmouth unless otherwise stated.