"Should architects design provocatively ugly architecture that does not conform to Instagram's aesthetic conventions?"

Instagram has had a huge impact on the architecture of our cities and perhaps it is time that this changed, says Will Jennings.

In just nine years, Instagram has risen from a fun photo-sharing app to a central element of contemporary culture. Instagrammable is now a recognised word, and as a verb "to Instagram" is threatening the traditional "to photograph". It has entirely reshaped marketing, subtly placing products into Instagrammers' photographs to such a level that the Advertising Standards Agency have released a Guide for Influencers helping audiences separate innocent posts from commercial promotion.

Architecture has not been immune, with Dezeen itself deeply embedded within Instagram culture, its annual Instagrammable top 10 from Milan design week becoming the go-to list of what's hot at the event. From nowhere, this app seems to have become a critical element of urban design.

There is a rich critical history of photography's relationship to architecture – from Frederick Evans' Sea of Steps, to the original Willhelm Neimann and Sasha Stones photographs of the Barcelona Pavilion reproduced throughout postwar design textbooks, through to Iwan Baan and his contemporaries re-imagining architectural form into two dimensions.

But shareable digital image making, and in particular the Instagram explosion, has radically shaken this slow evolution of place's relationship to its image.

From nowhere, this app seems to have become a critical element of urban design

Instagramming architecture is not the same as photographing it, carrying not only its own aesthetic and globally conformed standpoints, but an urgency and need for the image to work beyond art object and within an economy of likes, self-promotion, and social currency.

The slow process of architecture is now catching up with this rapid rise of aesthetic and social expectations, and a new genre of Instagrammable architecture has been emerging.

Obvious proponents of this are the likes of BIG and Heatherwick Studio, creating nu-iconic architecture in which the icon is not just a form designed for skyline or city branding but to work within digital swipes of the smartphone and as a site for a new form of urban occupation.

But it is not just starchitects creating this new vernacular, it is also developers with glass-bridge swimming pools and tightly curated placebranding, interior designers' selfie walls, and the moneymen (always men) throwing dollars at Instagram-friendly vanity.

Vapourwave and millennial-friendly colour palettes help with image likeability, and a strong sense of irony or moment of "fun" works. The Instagram aesthetic craves the pop-up urbanism, shabby chic and paint-on patina that we see uniformly decorating neighbourhoods regardless of country or context. Tiled floors do well, angel wing walls do better, and hints of vintage or industrial chic will attract the smartphone cameras.

The Instagram aesthetic craves pop-up urbanism, shabby chic and paint-on patina

The result is a series of transitionary spaces codified and recognisable the world over, which don't so much call for us to dwell in them so much as digitally record our presence, capture that moment then move on.

It removes the unexpected, the exploratory and sense of a local, creating a comfortable global aesthetic in which, without prompting, the inhabitant knows how to act and perform. You can even download an app to be guided directly to the nearest Instagrammable locations wherever you are, immediately offering a socially acceptable, conforming backdrop to your Instalife.

It is estimated that in 2017 over 1.2 trillion photographs were taken, with 85 per cent on smartphones. How many of these will ever be looked at a second time? Aside from huge environmental repercussions of storing huge amounts of image data – which if seen at all may barely be for a momentary swipe – it demands a rapidly evolving aesthetic in which place acts more as temporal stage-set than traditional civic infrastructure.

Instagram fetishises the temporal over the durational, and while studies suggest that certain uses of instagram may negatively affect personal wellbeing might it also be creating an urbanity that damages social cohesiveness and being in place?

It's interesting watching live selfie-taking. The protagonist holding their phone at arm's length, minutely tweaking the angle of their neck, reading their presence in space in mirror image, taking a photo, then repeating and repeating the process with near-identical poses before standing to one side, scrolling the mass of data and picking a single frame to share with the world.

Instagram transforms architecture from an experiential space to one of representation

They don't seem present in the place itself, but deeply concentrated on some dislocated, other place deep behind the lens of their phone. Selfie culture has affected design hugely, from selfie-sticks to huge development of the front-facing smartphone lens, and now too affects the shape of our cities.

Instagram transforms architecture from an experiential space to one of representation, and through this turns inhabitant into both consumer and consumed.

In visual art, Instagram has shifted exhibitions design. The Hayward Gallery marketed Space Shifters as "the most Instagrammable exhibition", while I struggled to find the Tate Olafur Eliasson blockbuster anything other than a culturally highbrow version of Instagram experiences like the Museum of Ice Cream or Selfie Factory.

Are our tightly curated urban spaces now following this same approach of episodically contrived moments designed around shareable and reproducible image making.

Some in the arts have hit back, concerned that prioritising a detached, digital experience damages the reading of their work. In 2012, Tino Sehgal banned visitors from photographing or recording his Tate Modern Turbine Hall installation These associations.

The performance work was centred around personal interaction between a member of the public and a performer who would step out of the choreographed crowd dynamics to initiate the engagement. Sehgal's work was partly created in response to increasing disengagement between visitor and artwork (visitors now spend an average of eight seconds looking at a piece), and enforced the ban as a strategy to return a sense of beingness and minimise the smartphone-mediated glimpse.

So what can architects do to pull back from clients' contractual demands for Instagrammable moments? Can an uninstagrammable architecture exist?

Similarly, musicians and comedians increasingly require audiences to secure their phone into lockers or bags which cannot be re-opened until after the performance. But I can't see any architects trying to enforce such a ban for all future users of their designs, nor is it rational at a time when the creep of private management of urban space prohibits activities such as photography already.

So what can architects do to pull back from clients' contractual demands for Instagrammable moments? Can an un-Instagrammable architecture exist?

Perhaps architects should design provocatively ugly architecture, buildings which demand not to be photographed by virtue of not conforming to the Instagram aesthetic conventions of form, colour, wow or irony.

However, we know late-capitalism always finds ways to commodify and squeeze capital where possible, especially from oppositionary forces. This is how imagery of 1968 becomes cat-walk fodder, landlords co-opt Soviet graphics, or how graffiti is adopted as a corporate place-making tactic, offering a pretence of grit and community without any political threat.

Concentrating design less on the iconic wow moment, and putting more emphasis upon transition and non-destination spaces would go a long way to returning urban design back to one of presence and away from exiting as curated backdrop.

If the city is becoming a series of standalone photographic moments, like the room-by-room Instagrammable installations of blockbuster art exhibitions, let's think more about the journey between those moments. The everyday architecture of the street and public space, so often considered secondary to the prime architectural object, deserves more care and attention.

Perhaps, though, Instagramming is a fad which is already passing. Who knows what digital platforms we will be using in another nine years, and how these will impact our experience and design of urban place? The risk is that to create an urban form which civically and environmentally should be designed with a longview of centuries over the instant marketable moment, we are simply building for a way of being in place which will be redundant before we realise.

Maybe this is a period we will look back on with bewilderment at the idea we were designing not for the immediate user in the physical place, but for the imagined perception of that user to a hypothetical digital audience.

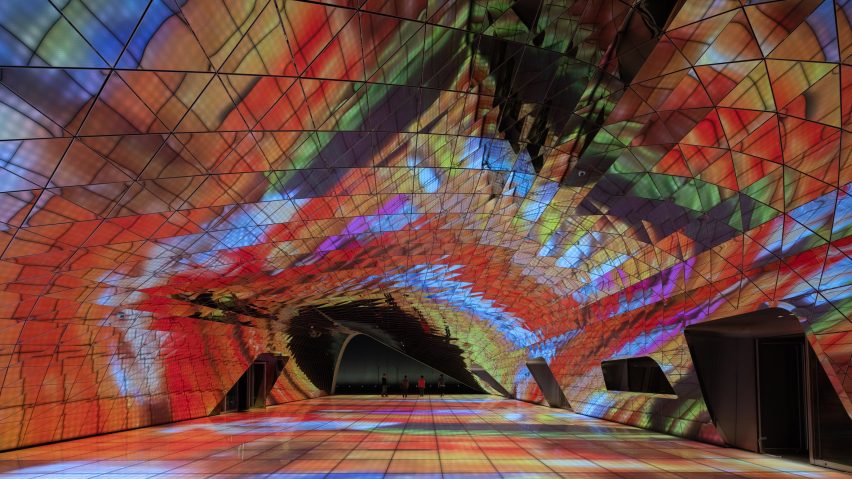

Main image is The Imprint by MVRDV. Photo is by Ossip van Duivenbode.