Solar Protocol network explores the potential of a solar-powered internet

Internet traffic is controlled by the "logic of the sun" in Solar Protocol, a solar-powered network whose creators argue for digital design within planetary limits.

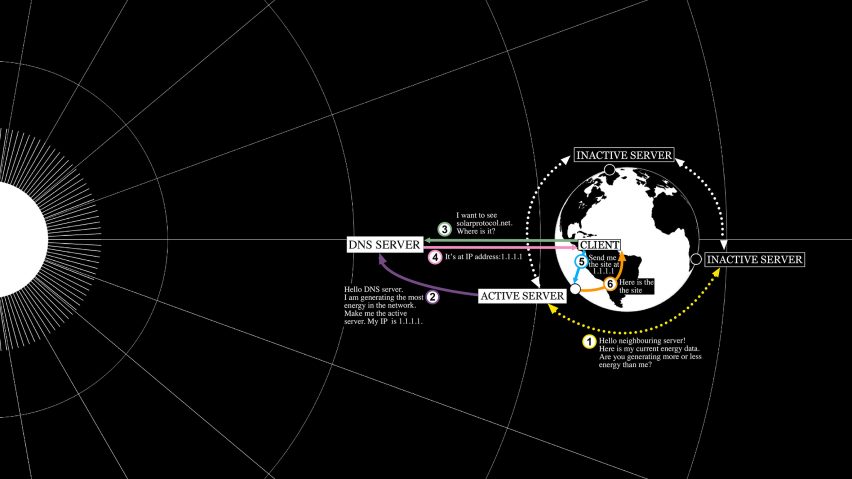

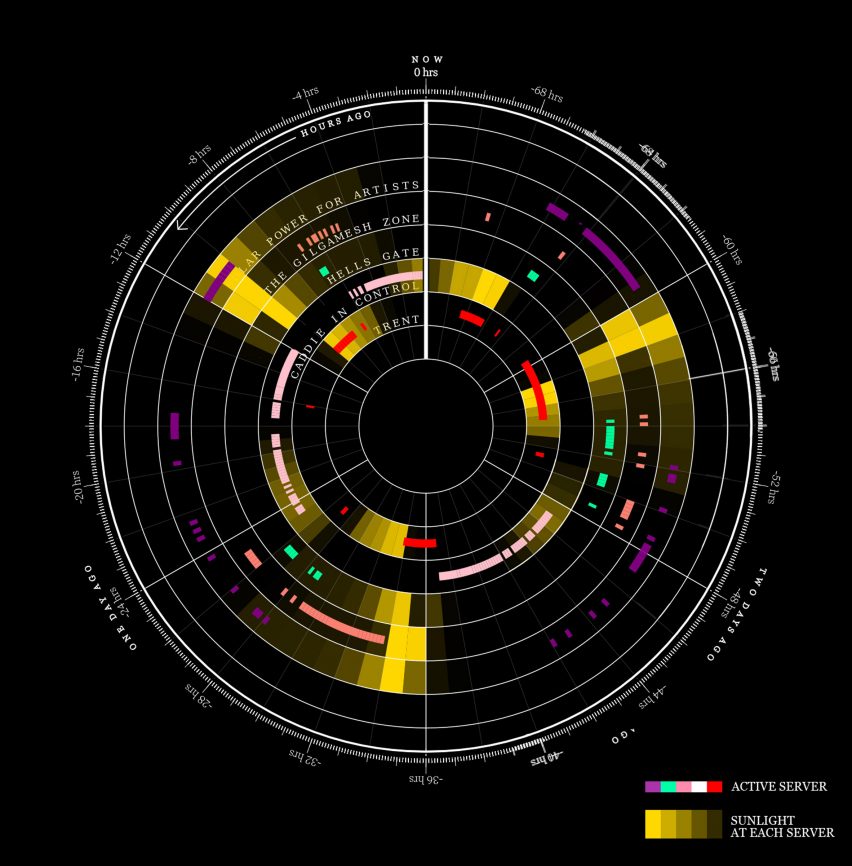

Solar Protocol involves a series of solar-powered servers, set up in locations across the world's time zones and serving its hosted websites from whichever spot is enjoying the most sunlight.

This subverts the typical operation of the internet, as usually when an internet user goes to access a website, their request is directed to whichever server gives them the quickest response — typically the one that is closest geographically.

The website might load slower for someone using the Solar Protocol, but the process will make use of the most naturally available energy, so it is optimised in a different way.

The network's creators — artists and New York University professors Tega Brain, Alex Nathanson and Benedetta Piantella — consider this the "logic of the sun", a way of designing by considering earthly dynamics such as the sun's interaction with the Earth.

They created Solar Protocol to get people thinking about the links between energy use and digital design, a topic that they say is hugely overlooked.

"In the field of computer science, there's always been this idea of computing being unlimited and infinite," Brain told Dezeen. "There's not a culture of considering the material impacts and the fact that these systems are reliant on giant energy-sucking, water-sucking data centres that are all around the world."

"A decision about, for example, whether you are going to run JavaScript or not, it doesn't matter, it's completely insignificant if it's just one. But if you scale that on the level of Google or Facebook, and you have millions or billions of users, it's enormously significant.

"We're trying to develop a different approach to design and particularly to UX design, where this thinking currently doesn't exist at all."

"We're really concerned about how to frame design as being within planetary limits and within the energy context," added Nathanson.

The creators are keen to qualify that their project is a provocation about how we use the internet and not a solution to its energy issues.

They don't advocate switching the entire internet to a solar protocol. Instead, they are using the experimental project to explore multiple intersecting ideas, including whether systems could be designed around "natural intelligence" as much as artificial intelligence, designing for intermittency, and questioning the primacy of high-resolution.

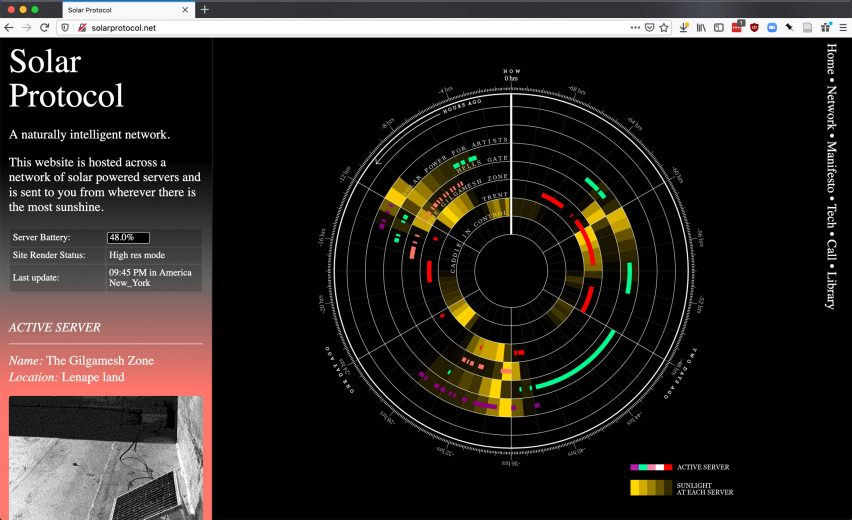

These ideas are explored on the Solar Protocol website and in a recent paper by the team on the site Computing Without Limits.

In the paper, they take aim at some expected targets – Web3 technologies such as cryptocurrency, they say, is "where computation is often expended for no use value whatsoever" – but also question the widespread use of streaming, machine learning and the internet of things. They reference an estimate that online video streaming could account for one percent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

"I think part of it is a question of values," said Nathanson. "The internet obviously enables incredible things all the time – like this phone call has less of an impact than if you were to fly here or if the three of us were to fly to London."

"But I do think it's fair to say that there are a lot of things like intermittency that are, because of climate and because of local economies, a really big factor in people's lives and will increasingly be so. And digital design needs to respond to that in order for us to be able to have fulfilling lives but also equitable and just worlds."

"One of the explorations was also to think about what are some things that you can live without and that maybe you benefit from living without at certain times of the day that," added Piantella. "This idea that this system isn't available to you 24/7 and it has its own rhythm is also a provocation in terms of one's own behaviour and thinking about, what are some things that you would like to go down when the sun goes down?"

The Solar Protocol network currently has nine servers hosting three websites: one for Solar Protocol itself, one for the Low-Carbon Research Methods Group and one for an Extinction Rebellion project. The creators are now working on turning it into a more expansive digital space hosting essays and artworks.

Read on for an edited transcript of our interview with Brain, Nathanson and Piantella, where they discuss their ideas on digital design within planetary limits, what it means to use "natural intelligence" and whether their proposals mean a "less fun" internet.

Rima Sabina Aouf: Where did the idea for Solar Protocol come from?

Benedetta Piantella: The first incarnation of Solar Protocol was an experimental research project into the idea of: what would it take to create a solar-powered server and have a solar-powered website. We were really inspired by Low-Tech Magazine, the solar-powered website. We were interested in the fact that within our programs and within our practice and within the subjects that we teach, we encourage everybody to have extensive online documentation and have an online presence and host blogs and have a multimedia presence online. But there's kind of a disassociation between that and the understanding that that presence has an environmental impact, and that the decisions that one makes online in terms of how you present your work or how big of a file you upload, or the resolution of the images that you post online, all come with an energy expenditure. And we use these metaphors like "the cloud" which make all of those actions seem very detached from natural resources.

We ran some experiments, we created one solar-powered website, and then out of that, I think the follow-up question was what would happen if we had a network of these servers and actually looked at how current protocols work and how could we partially reinvent a protocol or experiment with the idea of traffic being routed based on natural logic rather than traditional protocol logics based on efficiency and other things.

Rima Sabina Aouf: How did you organise the locations for where the different servers would be hosted?

Alex Nathanson: We have no aspirations for this to be like a giant, massive thing. Our idea of scale was, how do we get one site on each continent with the exception of Antarctica and get something that does this sort of poetic cascading effect as the Earth rotates. So that was sort of what we thought of in terms of the size of the network. But then for the individual sites, we started with, I would say, mission-aligned friends, and then slowly grew out from there.

Tega Brain: We did also do an open call. Some contacts came through that. This project began when we were locked down in New York, so it became this really interesting way of building a collaboration when you can't travel and when you can't leave your city. We're in touch with folks all over the world to set this up. There's been a lot of Zoom calls and like, peering into server boxes and trying to figure out circuitry and why someone's server's not working. It's also challenging because we can't really have a meeting with everyone because of the timezone thing, and it's hard to understand people's internet situations. We have a server in China that's never really worked because of the firewall VPN stuff. There's one in Dominica that's similar because it's a community network. It just shows you what a mess the internet is and how in every single country, it's different. Our Kenyan people had to move through three different ISPs before they could find one that would let them open up their ports! If you want to understand how the internet works, just try and open up port 80 in like 10 different countries, and you can see where it's at.

Rima Sabina Aouf: I want to get stuck into the ideas behind the project a bit more. I don't think many people consider their online activity as contributing to their carbon footprint or as part of political power structures at all. Could you comment a bit on that and why it's worthwhile to think this way?

Tega Brain: I think in the field of computer science, there's always been this idea of computing being unlimited and infinite. The example I always give is if you look at the Turing Machine, which is the conceptual idea for what a computer is that Alan Turing came up with in the 1930s, it's like this system that has a head that can read and write data on an infinite roll of tape. And that's the model for all computers, like all computing programmes can be run on this Turing Machine. And yet there's this infinite roll of tape in that concept! It produces this imagining that we will always be able to collect more data, store it, work with it.

There's not a culture of considering the material impacts and the fact that these systems are reliant on giant energy-sucking, water-sucking data centres that are all around the world. And this is becoming really obvious in Europe at the moment with the drought where data centres in The Netherlands are using like five times the water that they're supposed to be using, and now they're competing with agricultural water demand, because there's limited water resources. So this is an infrastructure that's hugely resource intensive. And so even just a decision about, for example, whether you are going to run JavaScript or not, it doesn't matter, it's completely insignificant if it's just one. But if you scale that on the level of Google or Facebook, and you have millions or billions of users, it's enormously significant. We're trying to develop a different approach to design and particularly to UX design, where this thinking currently doesn't exist at all. And of course, it doesn't exist, just look at what the leaders in the field are doing — Meta and Facebook and VR and blockchain and all these hugely computationally intensive approaches. The idea that you would actually consider computational work and try to design for that as well as the user and all the other things you design for is really not a mainstream position in design.

Alex Nathanson: We're really concerned about how to frame design as being within planetary limits and within the energy context. In the tech industry, efficiency is not about being more ecological or more sustainable. It's about squeezing out more financial gain from the same inputs. But in the environmental world, we would call that the rebound effect — the idea that more efficiency often leads to more energy consumption, which is a big problem. And so how do we design in a way that can minimise the risk of the rebound effect, within planetary limits, is a crucial piece of that that doesn't really exist in current design dialogue.

Rima Sabina Aouf: Would you say that the current way we use the internet presents an obstacle to the transition to renewable energy?

Tega Brain: Yeah! I mean, Ethereum. Today, they've finally gone to proof of stake after promising to do it for five years. So there are steps being made but the carbon emissions of the internet are equal or more to than aviation it's now estimated, so it's significant.

Benedetta Piantella: I think one of the explorations was also to think about what are some things that you can live without and that maybe you benefit from living without at certain times of the day. So this idea that this system isn't available to you 24/7 and it has its own rhythm is also a provocation in terms of one's own behaviour and thinking about, what are some things that you would like to go down when the sun goes down? What are some things that you actually want to lose access to? So that you can reclaim some of your time and also free up some of these resources.

Alex Nathanson: I think part of it is a question of values. The internet obviously enables incredible things all the time — like this phone call has less of an impact than if you were to fly here or if the three of us were to fly to London. So I don't think we're saying that the internet is an impediment to the energy transition or addressing climate, nor are we saying the solar protocol model is a model for addressing the climate crisis. But I do think it's fair to say that there are a lot of things like intermittency that are, because of climate and because of local economies, a really big factor in people's lives and will increasingly be so. And digital design needs to respond to that in order for us to be able to have fulfilling lives but also equitable and just worlds. If we look at California, where they have proactive shutdowns because of forest fires, we see that basically no matter where you are in the world, your intermittency is going to be a factor in in grid infrastructure. And we need to design for that to be able to address the climate crisis.

Tega Brain: It's great to figure out the supply side of things, where we use renewable energy, but we also need to look at the demand side and really ask questions about what we're using that energy for and what we're using the digital resources we have for. They're not just infinite free gifts of nature that have appeared from nowhere, right? This idea that we don't ever delete data and that we basically just hoard data for our whole lives, I think we really want to question that. And obviously that impulse has a relationship to AI and to machine learning — the reason why Google doesn't want you to delete emails is because they're running these huge natural language models. And that's valuable for their business model. And so it is entangled, I think, the cultural position of keeping everything and then these sort of larger-scale commercial forces.

Rima Sabina Aouf: In your manifesto you contrast artificial intelligence and "natural" intelligence, which follows "the logic of the sun". Is it odd to ask computers to use a natural logic?

Alex Nathanson: I think human-made systems have been interacting with the natural world since the first tool. I think it actually is more of an acknowledgement of the interconnectivity that we've always had between the infrastructure and the environment. Something like the idea of randomness is a really crucial part of computing. But to get true randomness, computers always have to interact with something in the physical world, usually, because that's really the only place it exists, otherwise you're dealing with like, pseudo randomness. It's an important part of cryptography. So there are these existing examples.

Tega Brain: We wanted the project to be a provocation or intervention into the AI conversation, where there's a great deal of excitement for automating decision-making with modelling with historic data that comes with all the problems of bias that have been really well discussed. Yet, automation is characteristic of all healthy ecosystems, right? If an ecosystem is in good shape, it's because it's not human-managed; there isn't a human hand in there that's making decisions and trying to maintain it. So automation, we live with it. It's everywhere. And yet I don't think there are a lot of examples of designing infrastructures that do use environmental automation to curtail their operation or make decisions and that's, I think, what we're really experimenting with here.

Rima Sabina Aouf: You're talking about minimising the amount of data that's being transmitted, and a lot of people are going to read this and think it just doesn't sound like a lot of fun to interact with this internet. Why would we accept or even want a less fun internet?

Benedetta Piantella: I want to interject first by saying we've been in the process of co-designing the next phase of this project with all of our collaborators, and I have to be honest, everybody has incredibly fun ideas! In terms of projects that this has inspired them to think about and design. And so I would argue that actually designing with constraints is one way in which you can come up with much more creative and inspiring approaches to things.

Tega Brain: I think again, I'm going to have a go at Meta. You look at the content they're releasing from their new VR platform, which is supposed to be "computing without limits", and it's just the most banal, awful stuff, right? So I think there's a misalignment there. It's not that if you have infinite computing resources, you're immediately going to come up with brilliant content. And I think constraints that come from these environmental rhythms and our environmental context are super rich and interesting to explore.

Alex Nathanson: But also, the most popular platforms today are hyper-constrained, right? Like TikTok or Twitter. How many characters do you get on Twitter? But it's incredibly popular. And part of that popularity comes from this idea of constraint. Obviously our project's incredibly different from these sprawling social media things. But constraint is essentially the rules of the game.

The images are courtesy of Tega Brain, Alex Nathanson and Benedetta Piantella.

Solar Revolution

This article is part of Dezeen's Solar Revolution series, which explores the varied and exciting possible uses of solar energy and how humans can fully harness the incredible power of the sun.