Norman Foster is high-tech architecture's international figurehead

We continue our high-tech architecture series by looking at Norman Foster, the architect of high-tech highlights for five decades including Reliance Controls in the 1960s, the Sainsbury Centre in the 1970s, HSBC in the 1980s, Stansted Airport in the 1990s and the Gherkin in the 2000s.

For all its radical concepts and early experiments, high-tech architecture's enduring legacy is as the sleek style of globalisation and rampant late capitalism – of corporate headquarters, airports, conference centres and, more recently, that of spaceports.

One of the most important practices behind the spread of this type of architecture – the creator of the originals that have spawned so many spin-offs – has undoubtedly been that of British architect Foster, propelled to household-name status through a global expansion and lauding of awards and titles virtually unprecedented in UK architecture.

With this came the emergence of the contemporary starchitect or celebrity architect, and the idea of the lone, usually male genius, which while weakened still lingers today.

Foster's image was as finely-tuned as his buildings: global travel – along with planes, skiing, marathon-running and turtle-neck jumpers – are central to the mythos, built up over decades and packaged in the almost hagiographic 2010 documentary How Much Does Your Building Weigh, Mr Foster?, but the beginnings of his career were far more modest.

Foster was born in Manchester in 1935 to working class parents, his father a machine painter for Metropolitan-Vickers (which Foster has occasionally cited as an early influence for his engineering-led architecture) and his mother working at a bakery. Leaving school at 16, he worked as a clerical assistant at Manchester Town Hall followed by two years in the Royal Air Force before being recommended to study architecture at Manchester University.

With no financial assistance (he was ineligible on account of having no A-Levels), Foster worked night-shifts and jobs alongside to support his studies – a reality perhaps more common of architectural study now that it was in the '60s.

"I sold furniture, worked in a bakery, a cold store and drove an ice-cream van. I also applied for scholarships and entered drawing competitions," Foster recalled in an interview with Jonathan Glancey in 1996.

"In 1959, I won 100 pounds and a silver medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects for a measured drawing of a windmill. I took off to Scandinavia to look at the new architecture and haven't stopped travelling since."

Upon graduating in 1961, Foster was awarded the Henry Scholarship to study for his masters at Yale University, where he would meet both Su and Richard Rogers (who had married in 1960), and study with tutors such as Paul Rudolph and Serge Chermayeff.

Foster returned to London in 1963 following a brief road trip around America with Rogers, which made a distinct mark on his architectural approach had been made. "It is no exaggeration to say I discovered myself through America," said Foster of these years.

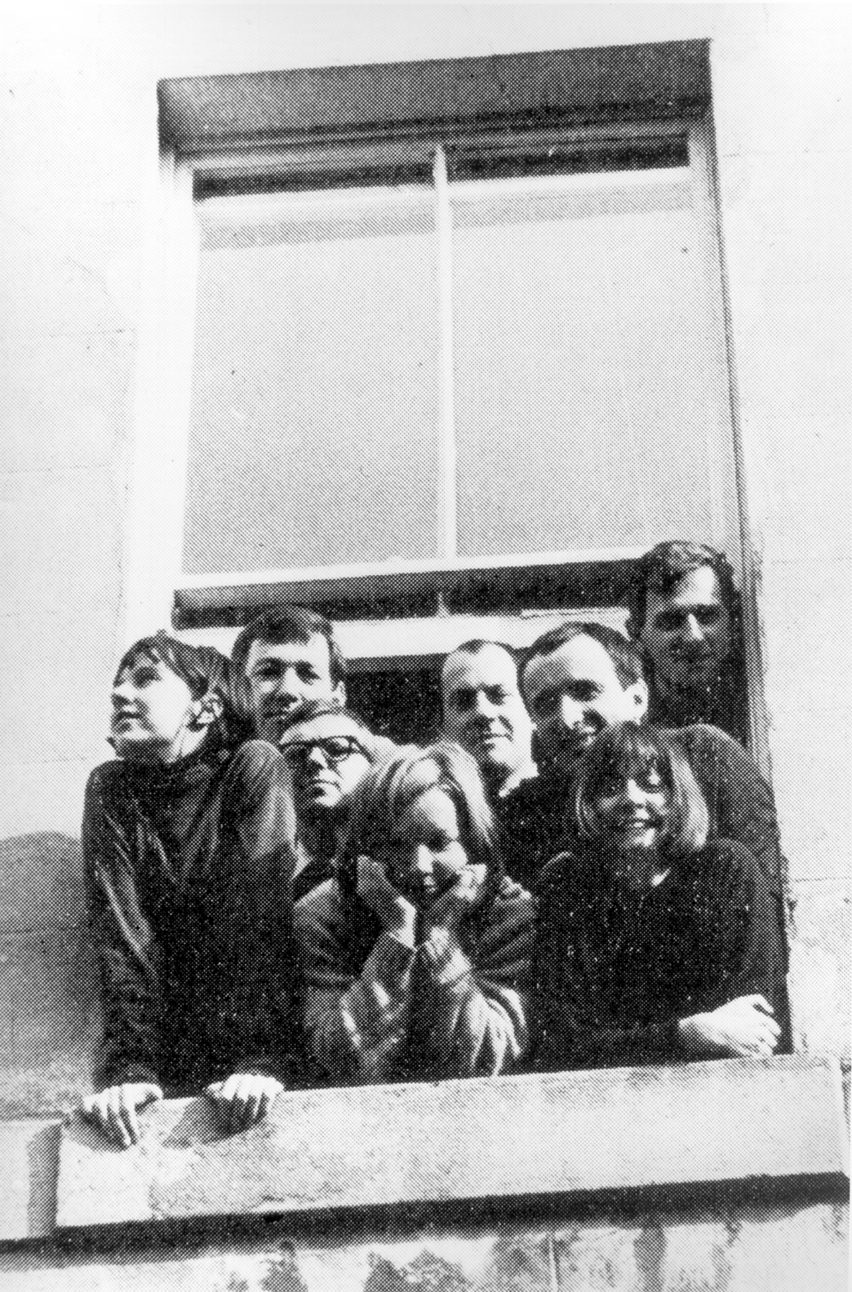

Foster's American odyssey, full of exciting examples of lightweight steel construction, fed straight into the designs of Team 4 – a practice formed by Foster, Richard Rogers, Su Brumwell and Wendy Cheesman (who would marry Foster in 1964) – working out of a front room in Hampstead.

Initially only able to build thanks to Wendy's sister Georgie, the only qualified architect among them, Team 4's work included the now-demolished Reliance Controls electronics factory, and the Creek Vean House in Cornwall designed for Brumwell's parents. Both of which saw the practice work with the engineer behind so much of British high-tech, Anthony Hunt.

Team 4 were exciting not only for their work but for their contribution to a changing image of the architect. When Team 4 split after just four years, the Rogers went to establish Richard and Su Rogers Architects and Norman and Wendy established Foster Associates in 1967.

The direction in which Foster wanted to take his and Wendy's practice was clear: he had huge faith in the new industrial style and its technology-led ambitions, and in the architect to be a driving force for this new age.

"Vast areas will soon be enclosed with lightweight space-frame structure or inflatable plastic membranes," he wrote in magazine BP Shield in 1969. "Full climatic control is feasible; the polar regions can be tropicalized and desert areas cooled."

While such ambition was typical of the British architectural scene at the time, few schemes allowing for such radical solutions made it past the drawing board. Among these were early collaborations with Buckminster Fuller, such as the unrealised project for the subterranean Samuel Beckett Theatre at St Peter's College, Oxford.

As something of a mentor, Fuller would drive Foster to create what he saw as an "environmentally sensitive" type of architecture.

"Bucky spoke frequently, for example, about the relationship between weight, energy and performance, of 'doing the most with least' – and that has consistently been the story of technological progress," wrote Foster of Fuller in the Observer in 2015.

But Foster Associates' actual commissions were, true to their high-tech stylings, the buildings of industry and offices rather than tropical domes in the Antarctic.

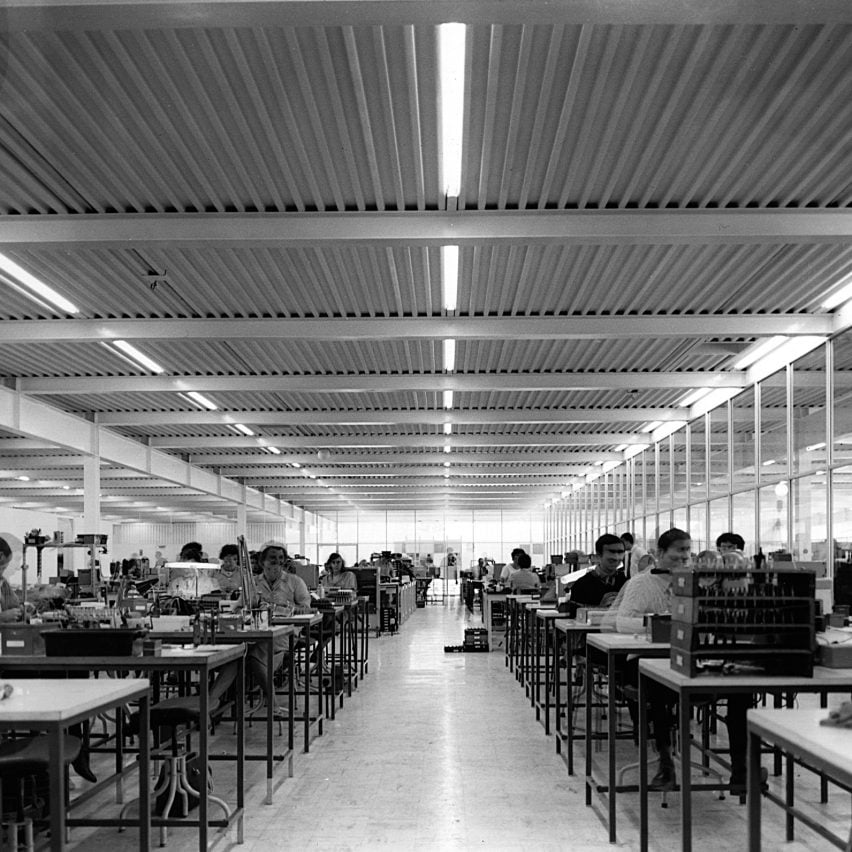

In 1972, the practice convinced IBM that rather than choose off-the-peg structures to build their new headquarters (if anything a rather high-tech approach), they should commission a cheaper bespoke space to become their Pilot Head Office.

Although originally designed as a temporary space, the sleek, aluminium-framed glazed box proved so successful that it was renovated in 1987 for continued use.

In 1975, the Willis Faber & Dumas headquarters in Ipswich garnered the practice attention for its rethinking of speculative office spaces, and in 1978 the sleek Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts engineered with Hunt brought the industrial, hangar-like aesthetic into the world of academic, cultural architecture.

But the real sea-change for the practice came in 1979, when Foster + Partners won an international competition to design the new Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation's headquarters, the brief of which was simply to build "the best bank headquarters in the world".

Established for little over a decade and having never built anything over three storeys high, Foster Associates suddenly found themselves with a budget of $600 million (at the time the most expensive building in the world), and working in a country completely unknown to them.

Undeterred, a small office of 12 staff set off for Hong Kong with partner Spencer de Grey as its director – this would eventually balloon to 150.

After the completion of the Hong Kong project the commissions began to roll in: first to design Century Tower, a speculative high-rise office project in Tokyo, and soon after Hong Kong International Airport, leading to the foundation of a new project office, Foster Asia, in 1993.

Having been a driving force in the key projects that set Foster Associates on the course to success, Wendy would sadly not live to see the opening of this second office, dying of cancer in 1989.

International celebrity had come remarkably early for the firm, seeing them preoccupied with overseas work during the height of the UK's Prince Charles-fuelled "style-wars" in the 1980s.

Besides, the 1982 designs for the Renault Distribution Centre in Swindon, with its Meccano-esque, bright yellow steel structure, demonstrated firmly which side the firm was on.

In 1991, however, the firm showed a hitherto unseen interest in working with existing structures with a project for the Royal Academy of Arts' Sackler Galleries. Much like many of his high-tech peers around the same period, this seemed to be an attempt to reconcile the high-tech with the historic.

However, rather than the Hopkins' approach of a "historicist high-tech", Foster's work remained that of radically modern insertions, and the project for the Royal Academy led to a slew of others: the renovation of the Reichstag in Berlin in 1999, the Great Court at the British Museum in 2000, and a new wing of the Joslyn Arts Museum in Nebraska in 1994.

The true high-tech spirit was not lost, however. The truss system of the Renault Distribution Centre would be carried through into the most notable example from this period: Stansted Airport in 1991, what Martin Pawley has called "a revolution in British airport design… a triumph of engineering, aesthetics and function."

Though now ubiquitous, the design's consideration of daylight and landscape for airport design set a trend that sees the practice still design airports to this day.

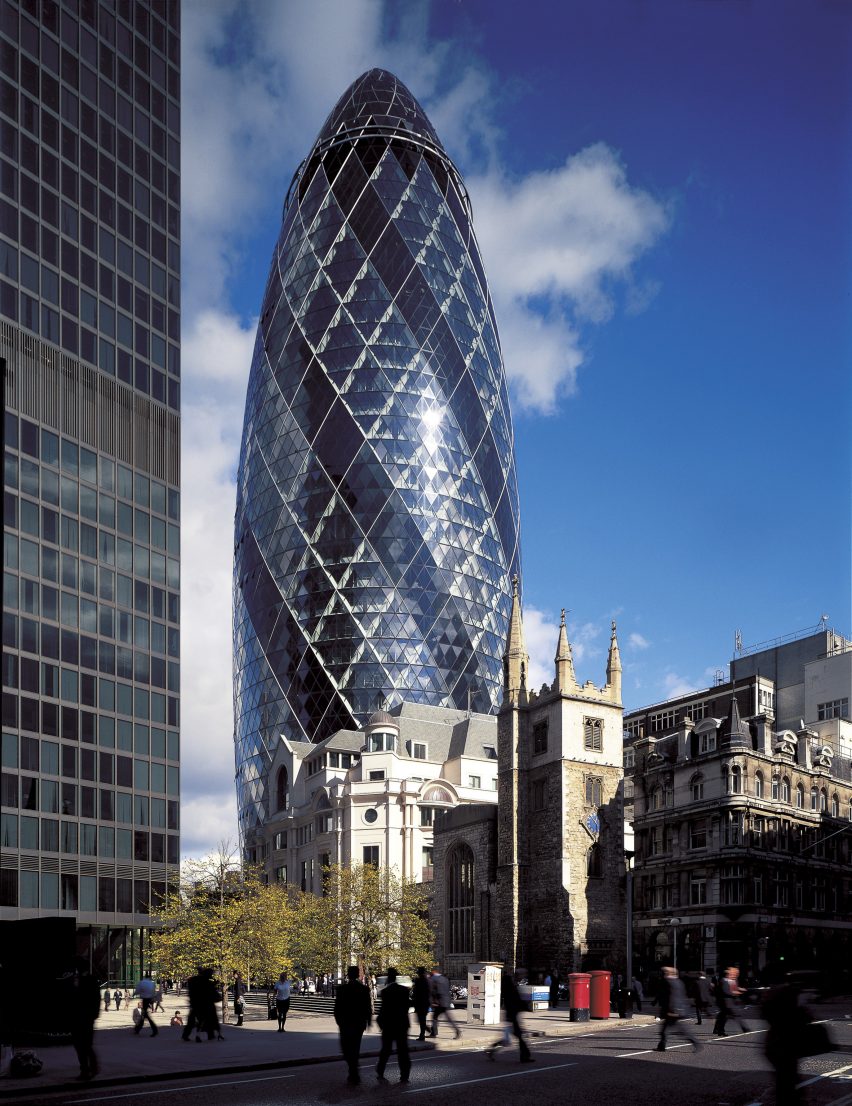

30 St Mary Axe, better known by its nickname, the Gherkin, would cement Foster as a household name for many in the UK. Completed in 2003 for reinsurance company Swiss Re, the Gherkin's smooth, elliptical form was created by a diagonal, twisting steel frame clad with flat triangles of glass. Internally, each floor is rotated in relation to those below to create spiral courtyards.

As the city's first "ecological skyscraper", this design was also to help cut ventilation costs by helping drive air through the building. A unanimous jury awarded the Gherkin the RIBA Stirling Prize in 2004.

More recently, the practice has been responsible to some of the largest corporate and commercial projects the world has ever seen – from the huge glass donut of the Apple Park in Cupertino (not to mention numerous Apple Stores), the Bloomberg Headquarters in London (another Stirling Prize winner in 2018), to the design of an entire capital city, Amaravati, in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, and a spaceport for Virgin Galactic.

A recent proposal for 3D-printed structures on the moon served as a reminder of the firm's distant radical high-tech roots.

Led by architects Foster, Rogers, Nicholas Grimshaw, Michael and Patty Hopkins and Renzo Piano, high-tech architecture was the last major style of the 20th century and one of its most influential.

Our high-tech series celebrates its architects and buildings ›

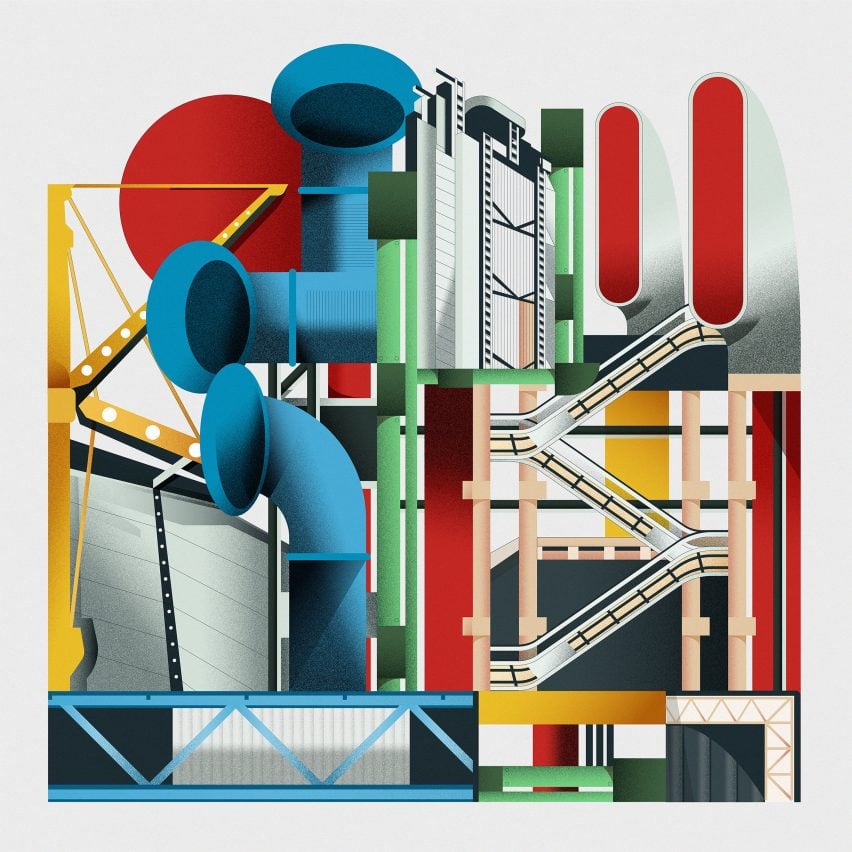

The main illustration is by Vesa Sammalisto and the additional illustration is by Jack Bedford.