Biofilm developed to power wearable electronics with sweat

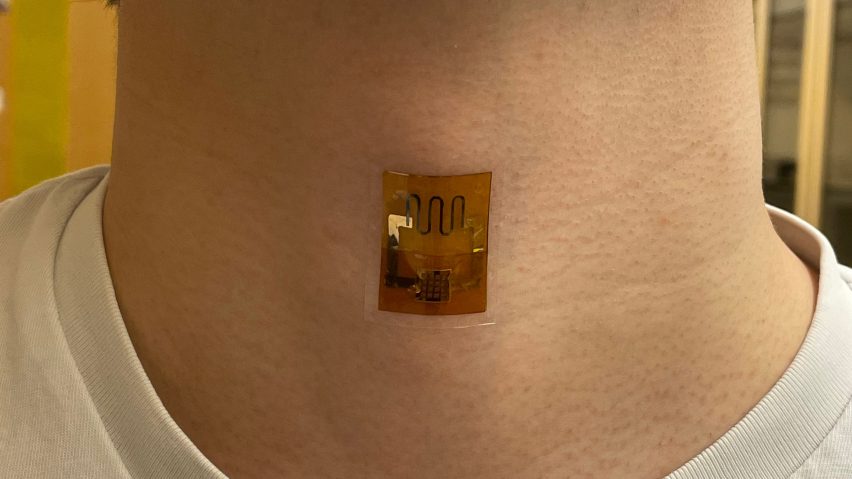

University of Massachusetts Amherst researchers have invented a biofilm that sticks to the skin like a Band-Aid to harnesses sweat for electricity that could power wearable devices.

The biofilm is made using a bacteria that converts energy from evaporation into electricity, making use of the moisture on a person's skin as it turns into vapour.

The University of Massachusetts Amherst researchers behind the innovation say it takes advantage of the "huge, untapped source of energy" that is evaporation.

"This is a very exciting technology," said team member and electrical and computer engineering graduate student Xiaomeng Liu. "It is real green energy, and unlike other so-called 'green-energy' sources, its production is totally green."

According to the researchers, this is because the film is produced naturally by the microbes, with no need for unsustainably produced materials and no toxic waste byproducts.

"We've simplified the process of generating electricity by radically cutting back on the amount of processing needed," said microbiology professor Derek Lovley, who is one of the senior authors of a paper the team has published in the journal Nature Communications.

"We sustainably grow the cells in a biofilm, and then use that agglomeration of cells. This cuts the energy inputs, makes everything simpler and widens the potential applications."

The bacteria used is called geobacter sulfurreducens and is known for its ability to produce electricity, having previously been used to make microbial batteries.

Unlike with those batteries, however, the biofilm bacteria do not need to be periodically fed or cared for, because they are already dead — one of the team's discoveries is that the microbes do not need to be alive to produce electricity.

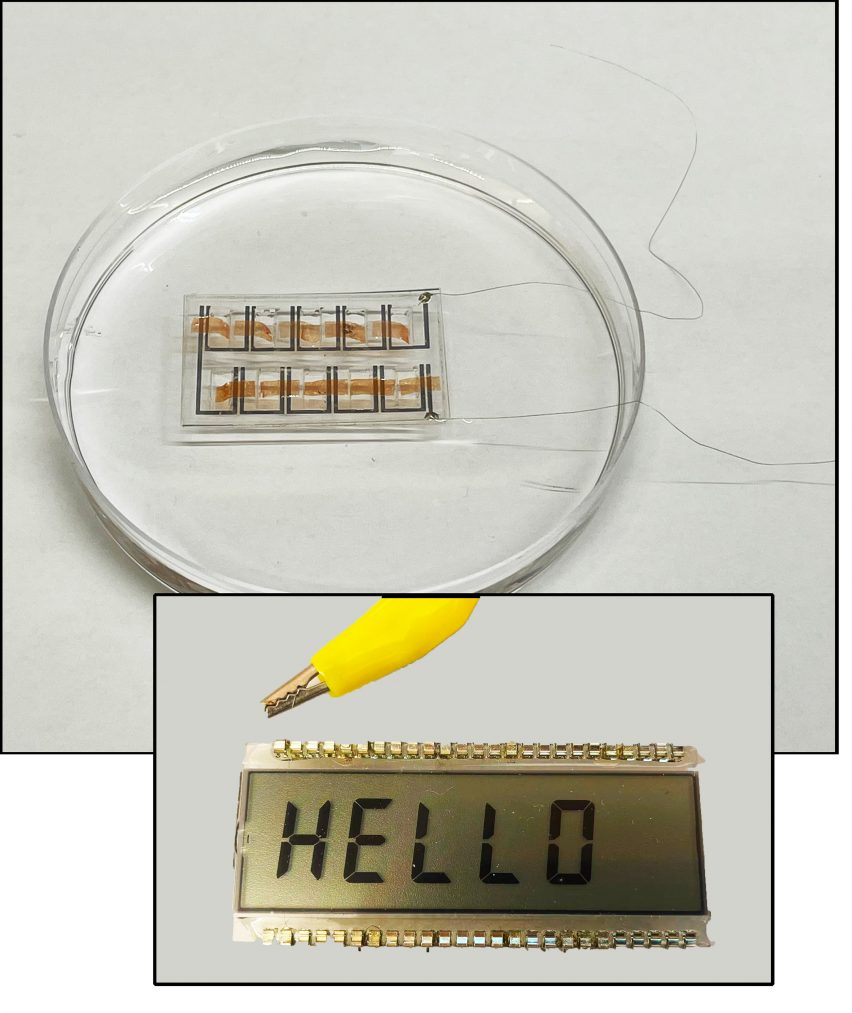

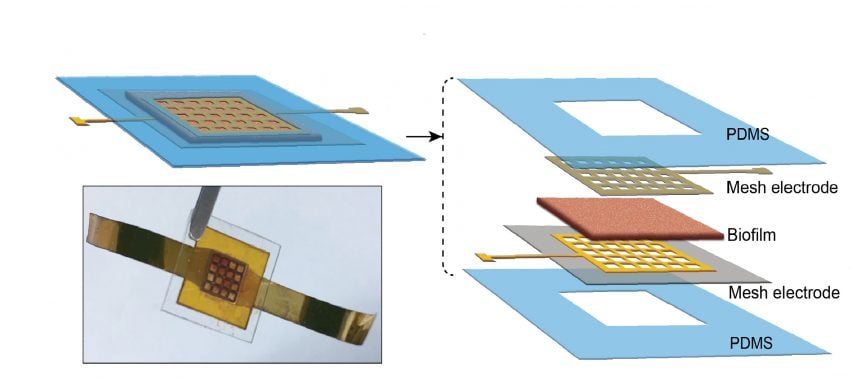

To obtain the biofilm, the researchers harvest the geobacter, which grows in colonies that look like thin sheets of under 0.1 millimetres thickness, with the microbes all connected to each other by "natural nanowires".

The researchers etch small circuits into these mats and then sandwich them between two mesh electrodes before sealing the package in a soft, sticky biopolymer to enable it to grip to the skin.

They describe the act of applying the film to your body as akin to plugging in a battery, and say it could revolutionise wearable electronics by solving the problem of where to put the power supply.

"Batteries run down and have to be changed or charged," said electrical and computer engineering professor Jun Yao. "They are also bulky, heavy and uncomfortable."

In its current form the biofilm produces enough energy to power small devices such as medical sensors or personal electronics, but the team also plans to explore larger films that can power even more sophisticated devices.

At an even larger scale, they hope the biofilm could be used to make more use of the untapped energy from evaporation, pointing to research that shows around 50 per cent of the solar energy reaching earth is spent on the process.

An example of a microbial battery appears in the work of Dutch designer Teresa van Dongen, who has used the geobacters to produce the Electric Life lighting and the Mud Well installation.

She embraces the fact that the bacteria need to be fed, arguing that this ritual would create "a closer relationship between the (living) object and its owner".