"Forensic Architecture winning the Turner Prize would risk turning sensitive investigative work into insensitive entertainment"

Forensic Architecture's Turner Prize shortlisting is a warning for architects to be vigilant of the arts world co-opting their work as grisly entertainment, argues Phineas Harper.

Here we go again. Once more an architectural collective has been nominated for the Turner Prize. Once more they stand just outside the profession with neither the organisation nor its staff to be found on ARB or RIBA membership registers. Once more they eschew conventional architectural practice but can regularly be found exhibiting in art galleries. Once more the nomination has raised eyebrows across the art and architecture worlds – not least within the collective itself.

"It's bittersweet," said Eyal Weizman, founder of Forensic Architecture giving a talk at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) shortly after the announcement, "more bitter than sweet."

He's not the only one with reservations. I have admired the work of Forensic Architecture for many years and do not doubt the sincerity of their investigations. They have added important new techniques to the forensic tool kit, exploded the traditional boundaries of what an architectural training can be used for, and shed light on human rights abuses around the world.

The use of criminal evidence as eye-catching exhibits for the entertainment is questionable

Nonetheless, the use of criminal evidence as eye-catching exhibits for the entertainment of gallery-going art consumers is questionable, and becomes more troubling as Forensic Architecture gain prominence in the art world.

In Counter Investigations, an extensive retrospective exhibition at the ICA, the curators show numerous short films succinctly presenting Forensic Architecture's evidence as if to a jury.

One room documents Forensic Architecture's investigation of the murder of two unarmed Palestinian teenagers shot from a distance outside Beitunia by Israeli police on Nakba Day in 2014.

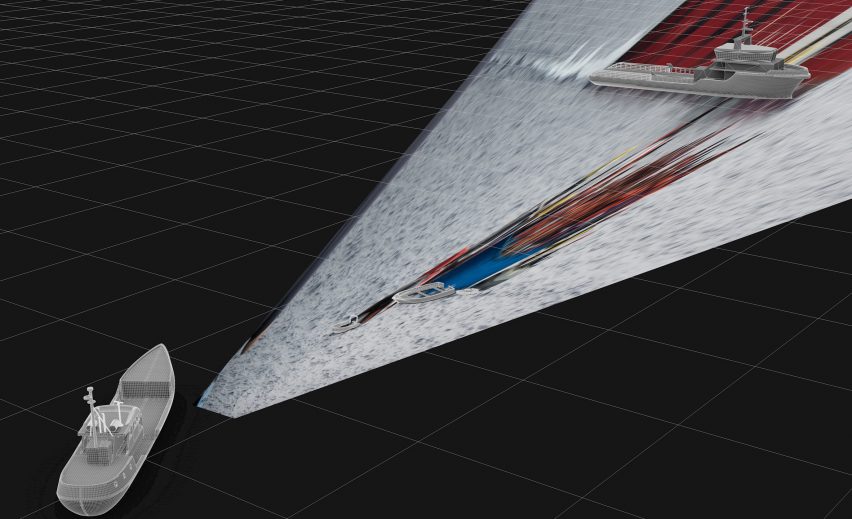

Footage of Nadeem Nayara and Mohammad Mahmoud Odeh Abu Daher's murders is repeatedly played back, slowed down, zoomed in, mapped onto 3D models, and cross-referenced with audio analysis, additional photography and rifle schematics. It is a frame-by-frame dissection of the two boys' brutal deaths.

The investigation was important and directly contributed to charges being brought against the notoriously difficult to prosecute Israeli police. However, its graphic presentation at the ICA borders on commodifying distressing material, which would typically be exposed to public eye with more caution. At times the film feels oddly cinematic, drawing upon similar visual tropes as hit TV cop shows like CSI. The ingeniousness of the investigators is centre stage as the crumpling bodies of the two boys fades into the background.

It is hard to see what Forensic Architecture's video will add to the situation other than a potentially traumatic spectacle

Not on show is Forensic Architecture's Grenfell Tower project. The architects intend to make an online 3D video of last summer's catastrophic fire generated from pieces of camera phone footage shot by members of the public. The project's visceral visual power is undeniable, but unlike at Beitunia, it is unclear what additional contribution the film will make to the investigations that are already underway.

The Grenfell Tower Inquiry includes 519 individuals and 28 organisations. The Building Research Establishment's report, leaked last month with full access to the site, was comprehensive; damning the tower's refurbishment. The Metropolitan Police continue to investigate using their own forensic techniques. Despite laudable intentions, it is hard to see what Forensic Architecture's video will add to the situation other than a potentially traumatic spectacle.

In 2009, one year before Forensic Architecture was founded, a fire at Lakanal House in Camberwell killed six people. The London Fire Brigade conducted their own forensic architecture making a digital 3D model of the building to map the route of the blaze.

In a strikingly similar process to Forensic Architecture's Grenfell plans, the model was used as an investigative tool to construct a detailed picture of the disaster incorporating witness statements, but was considered too sensitive to make public. Surely this discretion in the aftermath of a catastrophe is a more appropriate use of a forensic architectural model than exhibiting it to any gallery-goer's gaze.

Turner nomination is only the latest in a series of examples of arts bodies appropriating architecture

The Turner nomination is only the latest in a series of examples of arts bodies appropriating architecture in uncomfortable ways. In Venice later this month, London's V&A gallery will exhibit the scavenged caracas of a three-storey council flat that was once part of Alison and Peter Smithton's Robin Hood Gardens.

The curators say the move ensures the architecture will be preserved "for future generations", but have rightly been called out as hypocrites having explicitly refused to support a campaign that could have saved the block from demolition. This would have preserved not only the entire structure, but also the residents and community that gave the Smithsons' architecture meaning.

When you take the remnants of a council flat to the Venice Biennale, what are you really exhibiting? Fragments of historic British architecture perhaps – but also the suffering of the 213 families who once called Robin Hood Gardens home, some of whom will still be living in the block as their neighbours' homes are torn down around them.

It is the appalling treatment of poor people which is at the real heart of the show and betrays a blunt curatorial callousness. The true subject of the V&A exhibition, as with the ICA's, is people in pain, architecture is just the lens through which we ogle them.

The true subject of the V&A exhibition is people in pain, architecture is just the lens through which we ogle them

Last year MoMA demonstrated a similarly voyeuristic fascination in the intersection of architecture and suffering. Their Insecurities exhibition featured IKEA's flat pack refugee shelter surrounded by a mixture of objects seemingly identified by the curators Googling "refugee" and "architecture", without further discernment. Displaced people were treated as a homogenous mass with little discrimination between Syrians fleeing war, Kenyans born in semi-permanent city-camps and Mexicans seeking better paid jobs in America.

Architects must be more critical of the lure of the art world. I understand the appeal – blockbuster exhibitions have become the new middle class rock concerts. Celebrity curators are pursued by armies of Instagram fans. But the art world is not immune to toxifying market pressure. As institutions and curators compete to attract customers and notoriety, they must constantly stake out new headline-grabbing territory.

The Turner nomination demonstrates Forensic Architecture's stalwart form of investigative practice is at risk of becoming commercialised as a particularly grisly disaster aesthetic. Worse, the new artist status may even weaken Forensic Architecture's investigations. Weizman has described how pro-Assad groups have sought to dismiss their work with Amnesty International exposing Syrian torture. "[they] accused us of being 'artists' of being special effects, of fabricating the evidence", he explained.

Forensic Architecture winning the Turner Prize would risk turning sensitive essential investigative work into insensitive frivolous entertainment.