Architects in China adapting to more sustainable and culturally relevant skyscrapers after supertall ban

China's decision to ban supertall skyscrapers "will not hinder the potential of architecture" and is in fact leading to more sustainable, culturally sensitive buildings, architects have told Dezeen.

After the Chinese government announced a full ban on skyscrapers taller than 500 metres last October, architecture firms working in the country have had to adjust their approach.

Buildings taller than 250 metres are also now "strictly restricted" as the spotlight turns onto the sustainability and cultural relevance of China's architecture.

"While China ranks top in terms of total number and annual growth rate of supertall buildings, issues such as costs, energy consumption, safety, and environmental impact have become an increasing concern," deputy minister of the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MOHURD) Yan Huang said in a press conference after the announcement of the ban.

But far from spelling the end of high-rise building in China, the new regulations and sensibilities are leading to a fresh wave of architectural innovation, architects have told Dezeen.

The global standard definition for supertalls is 300 metres, though in China the term is sometimes applied to buildings 100 metres and above.

In the past decade, dense and growing urban populations, severe land shortages and hefty land prices in major Chinese cities have contributed to a frenzy of supertall skyscraper developments.

According to the US-based Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH), 56 of the 106 buildings taller than 200 metres constructed in 2020 were in China.

The world's most populous country is home to 2,581 buildings that are over 150 metres in height, including 861 above 200 metres and 99 above 300 metres.

More recently, however, China's love affair with supertalls has come under strain following a spate of half-finished buildings, empty towers and environmental and safety concerns.

In one prominent case, the 356-metre SEG Plaza in Shenzhen started shaking last May and was evacuated for four months while it underwent modification.

There is also the issue of skyscrapers being abandoned. According to CTBUH, as of September 2020 there were 81 unfinished skyscrapers in China where construction had been suspended, among which 66 are expected never to be completed.

In the city of Dongguan in southern China for example, while new office buildings have been sprouting up in the recently relocated city centre, those in the old financial district have a staggering vacancy rate, leading to unsalvageable financial losses for developers.

By October last year, MOHURD and the Ministry of Emergency Management had had enough.

They issued a joint notice on "strengthening the planning and construction management of supertall high-rise buildings", stipulating that development of supertall buildings over 500 metres must stop nationwide.

Cities with populations of less than three million must also restrict the construction of high-rise buildings of more than 150 metres and ban those above 250 metres outright.

Larger cities must restrict the construction of new buildings over 250 metres, meaning the application and approval process will become much more difficult.

After the announcement, a series of ongoing projects were forced to revise their original designs.

Ronald Lu and Partners (RLP) slashed the Wuhan Chow Tai Fook (CTF) Financial Centre from 648 metres to 475 metres.

The height of under-construction Suzhou Zhongnan Centre was finalised just under the threshold at 499.15 metres, down from an originally planned 729 metres.

It was designed by US firm Gensler, whose Shanghai Tower is currently the second-tallest building in the world.

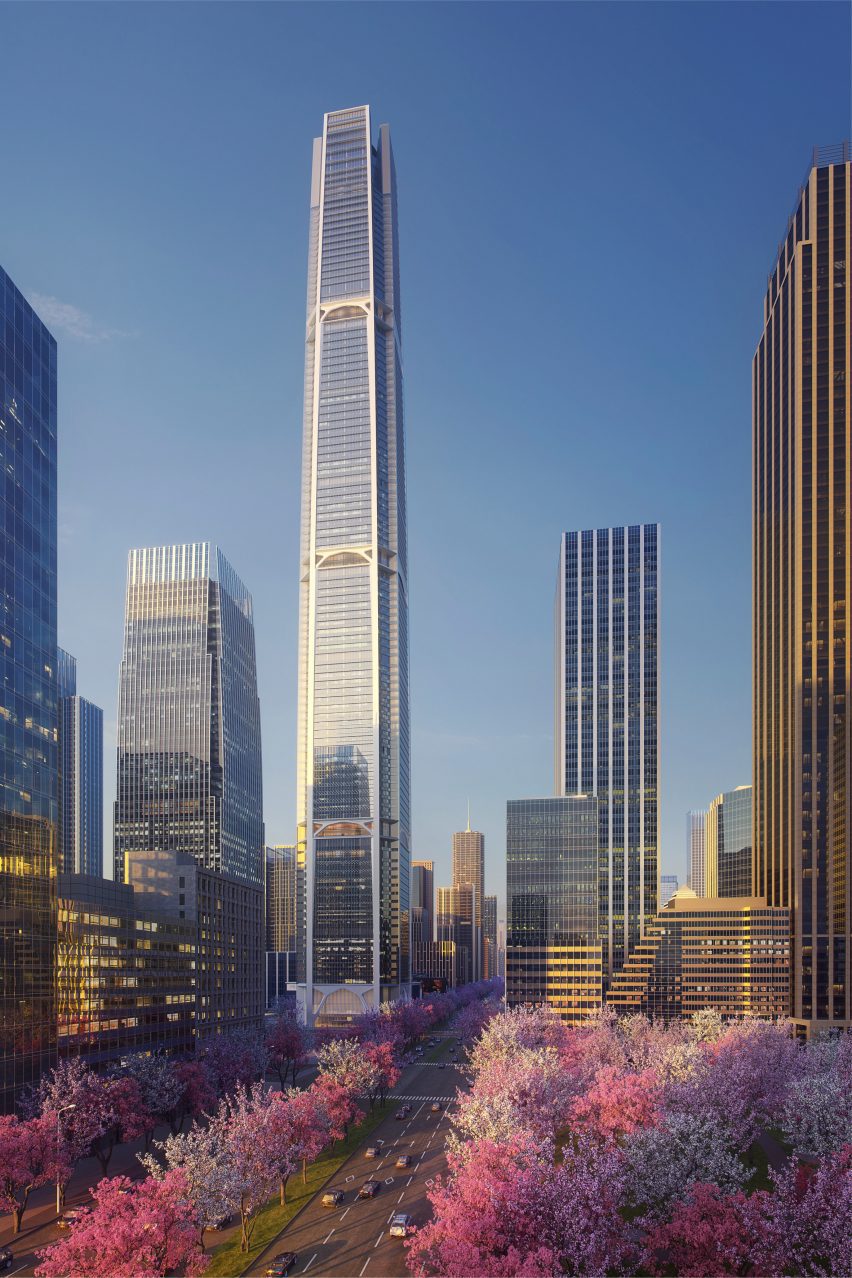

Similarly, Nanjing Greenland Jinmao International Financial Centre, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) is currently under construction and set to become the tallest building in Jiangsu Province with a height of 499.8 metres.

The building is an example of how the supertalls ban does not necessarily signal the end of unusual high-rise design in China.

SOM used structural arches to collect and redirect gravity to the four corners of the tower where they contribute to its structural efficiency, while also evoking the curved gateways of Nanjing’s ancient city walls.

"China's unique high-density high-rise market demands innovative building types," Aedas global design principal Andy Wen, who has a track record of building skyscrapers in China, told Dezeen.

"So even the introduction of the latest height restriction will not hinder the potential of architecture to make full use of the land," he continued.

Architects are having to respond to the environmental worries that are partly behind the new regulations.

China has announced a roadmap to see carbon emissions peak before 2030 and become carbon neutral by 2060, which means more energy efficient and sustainable architecture is now more likely to get state backing.

Like in the rest of the world, architects in China are aware of the part they play in achieving these aims.

"Architecture plays a vital role in reducing carbon emissions, and architects must incorporate that mindset into their design process," said Bryant Lu, vice chairman of Hong Kong-based studio RLP.

"Building supertalls is still a viable solution in large megacities of high density," SOM’s design partner Scott Duncan told Dezeen. "What is technically challenging about designing tall buildings today is how to do so while using less material — less concrete, less steel — to reduce the impact on the planet’s resources".

"Efficiency and smart engineering are the keys," he said. "We are seeing tremendous demand for natural ventilation in tall buildings, driven both by pandemic considerations and a desire to save energy, and this is not easy to achieve."

"We have moved away from the idea of a building as a hermetically-sealed bubble, and instead talk about breathing buildings," Duncan added.

Clean-cut glazed facades have come to define the modern skyscraper, with eight of the world's 10 tallest skyscrapers wrapped in large expanses of glass.

Glass towers provide well-lit interiors and double as viewpoints, but require high levels of air conditioning, making them notoriously energy inefficient.

The WeBank headquarters in Shenzhen, also designed by SOM and nearing completion, is instead fully breathable, with a network of atriums that act like lungs for the building's large, mezzanine-style floors.

"There is enormous risk in designing buildings of any height that don't provide these kinds of sustainability measures going forward," said Duncan.

Vertical forests – towers with facades covered in plants – have also been gaining popularity in high-rise design over the past decade thanks to their energy-saving capacity for helping to regulate building temperatures.

Italian studio Carlo Ratti Associati has unveiled plans to build a 218-metre-tall skyscraper in China that would grow crops using hydroponics.

The 51-storey building proposed dedicates 10,000 square metres to the cultivation of crops, creating a vertical hydroponic farm.

It is expected to produce 270 tonnes of food per year, enough to feed roughly 40,000 people, creating a self-sustained food supply chain that manages cultivation, harvest, sale and consumption all within one building.

Meanwhile, the lush green on the 220-metre-tall office building Treehouse in Hong Kong, designed by RLP post-supertall ban, not only serves as a visual centrepiece but also provides self-shading inclined facades on the upper floors.

The project won the architecture category at Hong Kong Green Building Council's Advancing Net Zero Ideas competition.

Some studios are finding other ways to make sure their high-rise projects appeal to the authorities.

For example, China's General Office of the State Council previously signalled its desire to see transit-oriented development (TOD), which puts large construction projects hand-in-hand with railway improvements.

RLP is particularly interested in TOD and has used it to win support for a project well above the 250-metre "strictly restricted" threshold.

"Transit-oriented development is one of the architectural forms that maximise land use," RLP's Lu told Dezeen. "By reconnecting the transport system with nearby communities, the land is put into maximum usage."

Wuhan CTF Financial Centre, designed by RLP and currently under construction, is one of the latest examples of urban TOD in China.

It comprises a 475-metre-tall office building, two residential towers, and other commercial complexes, all connecting two urban rail transit lines.

"Alternatively, we can revitalise existing land resources, such as through transformation of old factories and less developed towns and villages, to achieve efficient reuse of space with reasonable layouts while improving the residents' living conditions," added Lu.

The Hong Kong-based studio recently revealed its redevelopment plan for Nanji Village in Haizhu district, Guangzhou.

This former "urban village" suffers from frequent floods during the monsoon season, while its transport and drainage infrastructure desperately needs an upgrade.

In response, RLP dug water canals into the village, reducing the threat of flooding and providing a better landscape for the local community.

Meanwhile, the studio preserved some of Nanji's historical buildings such as the old Guangzhou Shipyard, the ancestral hall of the historical ruling clan, and the Pak Tai Temple, but also added the Folk Culture Exhibition Hall and Central Square.

"I see no problem pursuing supertall skyscrapers, as long as their design reflects local culture and historical value," said Wen.

"Urban landmarks must first of all possess powerful shape and form, while incorporating relevant culture, events, and history into their presentation," he added.

Duncan predicts that China's attraction to skyscrapers is unlikely to disappear, but will be judged differently in the future.

"To the question of what makes a good landmark, I would certainly point to skyscrapers, because, if done well, they represent the pinnacle of engineering of their time," he said.

"The existential challenge before us now is how to achieve a better balance with our ecosystems, so the landmarks of our future will likely be those structures that most intelligently respond to that challenge."

Dezeen is on WeChat!

Click here to read the Chinese version of this article on Dezeen's official WeChat account, where we publish daily architecture and design news and projects in Simplified Chinese.